A.J. Wright

Birmingham, Alabama, USA

|

|

|

|

| Burgess Scruggs2 | Cornelius Nathaniel Dorsette3 | Hale Infirmary, Montgomery, Alabama4 | Halle Tanner Dillon5 |

|

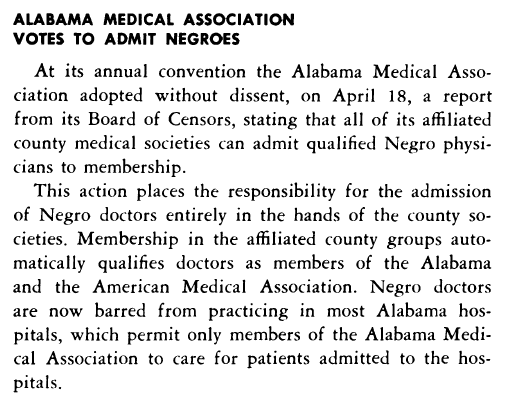

| Alabama Medical Association Votes to Admit Negroes1 |

There is a brief but interesting note in the July 1953 issue of the Journal of the National Medical Association, the official voice of the organization founded in 1895 for African-American physicians in the U.S. At first glance this decision by the Medical Association of the State of Alabama—as it was formally known—seems astonishing. Brown v. Board of Education had been argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in December 1952, but it would be reargued in December 1953, and the fateful decision was not handed down until May 1954. In the coming years the state of Alabama would be on the forefront of fighting not only Brown but any and all efforts to end segregation in the public sphere.

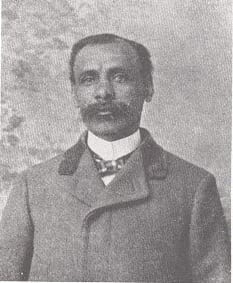

Alabama’s heritage of African-American physicians began when Dr. Burgess E. Scruggs (1857?–1934), a graduate of Meharry Medical School in Nashville, Tennessee, opened his practice in Huntsville in 1879. Scruggs would spend his entire professional life in the county where he was born a slave. He owned both city property and a farm and served four terms as alderman in the 1880’s and 1890’s.

Also born a slave was Cornelius Dorsette (1852?–1897), a classmate of Booker T. Washington’s at Hampton Institute in Virginia. Although he began his career in New York, he soon wanted to leave and consulted Washington for ideas. Washington, who by that time was at Tuskegee, convinced him to come to the state capital of Montgomery. Dorsette managed to pass the certification exam, and practiced in the city until his death. He also served as Washington’s personal physician. Dorsette persuaded his wealthy father-in-law to fund Hale Infirmary, the first such facility for blacks in the state, which operated until 1958. Dorsette also mentored Halle Tanner Dillon, who in 1894 became the state’s first female certified physician.

|

|

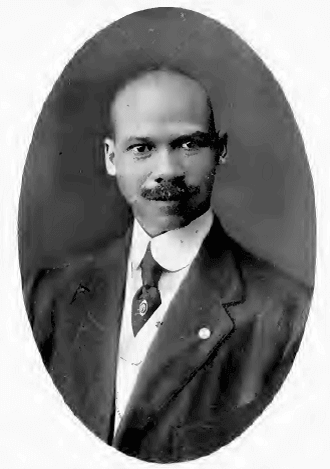

| Arthur M. Brown6 |

Dillion (1864–1901) was the daughter of Benjamin Tanner, a prominent clergyman in Pittsburgh and younger sister of painter Henry O. Tanner. Not long before she graduated from the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1891, Booker T. Washington contacted Dean Clara Marshall. He described his need for a resident physician at Tuskegee, and she recommended Dillon. Dorsette tutored Dillon before her certifying exam in August, where she faced several white males who were prominent members of the state medical society. She passed the grueling exam and worked for several years, caring for Tuskegee students and faculty. She was paid $600 annually, room and board, and a month’s vacation. In 1894 she married a mathematics professor at the college, and they soon left. She died in Nashville after giving birth to their three sons.

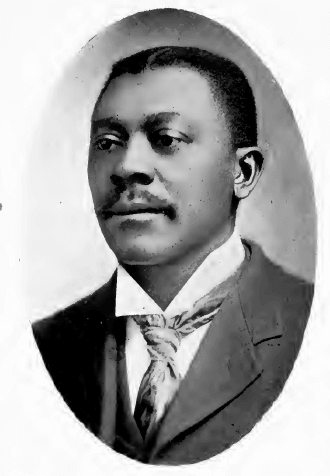

Arthur McKinnon Brown (1867–1939) was born in North Carolina and graduated from medical school at the University of Michigan in 1891. He moved to Alabama and practiced in Birmingham for many years. He served as a contract surgeon for the 10th Cavalry in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, helped start the Children’s Home Hospital, and worked with fellow doctor Ulysses G. Mason and others to improve education for blacks in the city. Active in local civic groups, Brown also participated in state and national black physician groups. He served as President of the National Medical Association in 1914.

Ulysses Grant Mason was born in Birmingham and graduated from Meharry Medical College in Nashville in 1895. He returned to his native city and remained there until his death. He did go to Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1899 for a course in surgery. He founded both C.M. Hall Hospital and Northside Infirmary for his black patients. Mason was also active beyond medicine. Along with Dr. Arthur Brown and others he worked to improve schools for blacks in Birmingham. He served as Vice-President of the Alabama Penny Savings Bank and as a delegate to Republican National Conventions in 1908 and 1912.

|

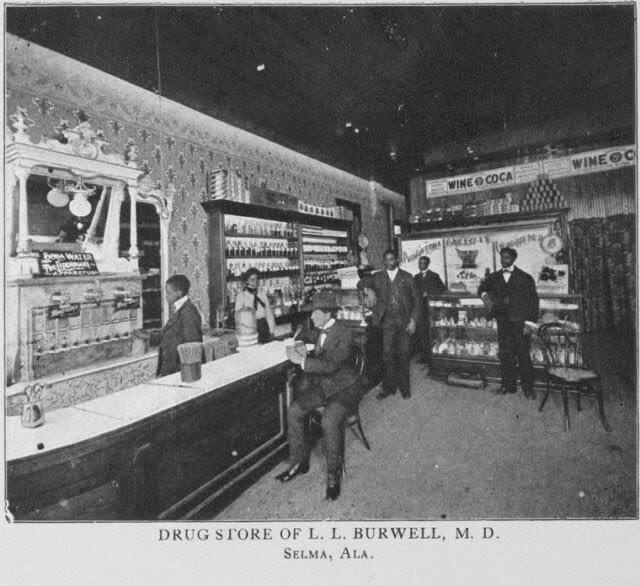

| Burwell’s Drug Store, Selma, Alabama7 |

Lincoln Laconia Burwell (1866–1928) opened his practice in Selma in 1890; the Alabama native remained there the rest of his life. He operated a modern pharmacy with soda fountains and seating, rooms for consultations, and a telephone booth, which was unusual at the time. In 1907 he opened Burwell Infirmary, which operated into the 1960’s. He was active in local civic and religious organizations and institutions and successful enough to send his two daughters to Oberlin College in Ohio.

Willis Edward Sterrs (1868–1921) was the first black physician in Decatur. He graduated from the University of Michigan medical school in 1888 and first set up practice in Montgomery, his native city. After moving to Decatur he opened the Cottage Home Infirmary in 1900 and added a nurse training school in 1910. Dr. Sterrs drowned while fishing on a local lake.

John A. Kenney (1874–1950) worked at both Tuskegee Institute and the town’s Andrew Memorial Hospital from 1902 until 1924. In that year Kenney was forced to leave the state due to Ku Klux Klan intimidation over possible black staffing at the new Veterans Administration hospital. He had a private practice in Newark, New Jersey, from 1924 until 1939, when he returned to Tuskegee as medical director of Andrew Memorial until 1944. Kenney worked tirelessly to improve black physician education via annual clinics during both his periods in Tuskegee. He also served as editor of the National Medical Association’s Journal for 32 years and authored the important 1912 book The Negro in Medicine.

These physicians and many others were all certified under the Alabama Medical Practice Act of 1877. Each one passed written and oral examinations administered over several days by white male physicians who were members of county medical boards or the state medical board in Montgomery. Most of these doctors published articles in professional journals, and participated in both professional and local civic organizations. By the time the state medical society finally “admitted” them, dozens of black physicians had practiced in the state.

|

|

|

|

| Ulysses Grant Mason8 | Lincoln Laconia Burwell9 | Willis Edward Sterrs10 | John A. Kenney11 |

Image credits

- Journal of the National Medical Association 1953 Jul; 45(4): 291. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2617397/.

- H.F. Kletzing & W.H. Crogman, Progress of a Race, or, the Remarkable Advancement of the Afro-American Negro, 1898.

- Amsterdam News [N.Y.] October 6, 2016.

- Clement Richardson, National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race, 1919.

- BlackPast.org.

- Clement Richardson, National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race, 1919.

- John A. Kenney’s The Negro in Medicine, 1912.

- Clement Richardson, National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race, 1919.

- Clement Richardson, National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race, 1919.

- Towns, Peggy Allen. Duty Driven: The Plight of North Alabama’s African Americans During the Civil War. 2012.

- Clement Richardson, National Cyclopedia of the Colored Race, 1919.

A.J. WRIGHT, MLS, served as a librarian for the Department of Anesthesiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine from 1983 until 2015. He can be found on Twitter as @AJWrightMLS.

Spring 2018 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply