Jason J. Han

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

The arteries of the heart are called coronary arteries, meaning “of a crown.” Like a crown, they course around and adorn the walls of the heart, keeping it alive with vital nutrients and oxygen. When these arteries are blocked, the heart starves, causing crushing chest pain and robbing people of breath as they walk or climb stairs. Eventually, this may lead to the death of the heart and its holder.

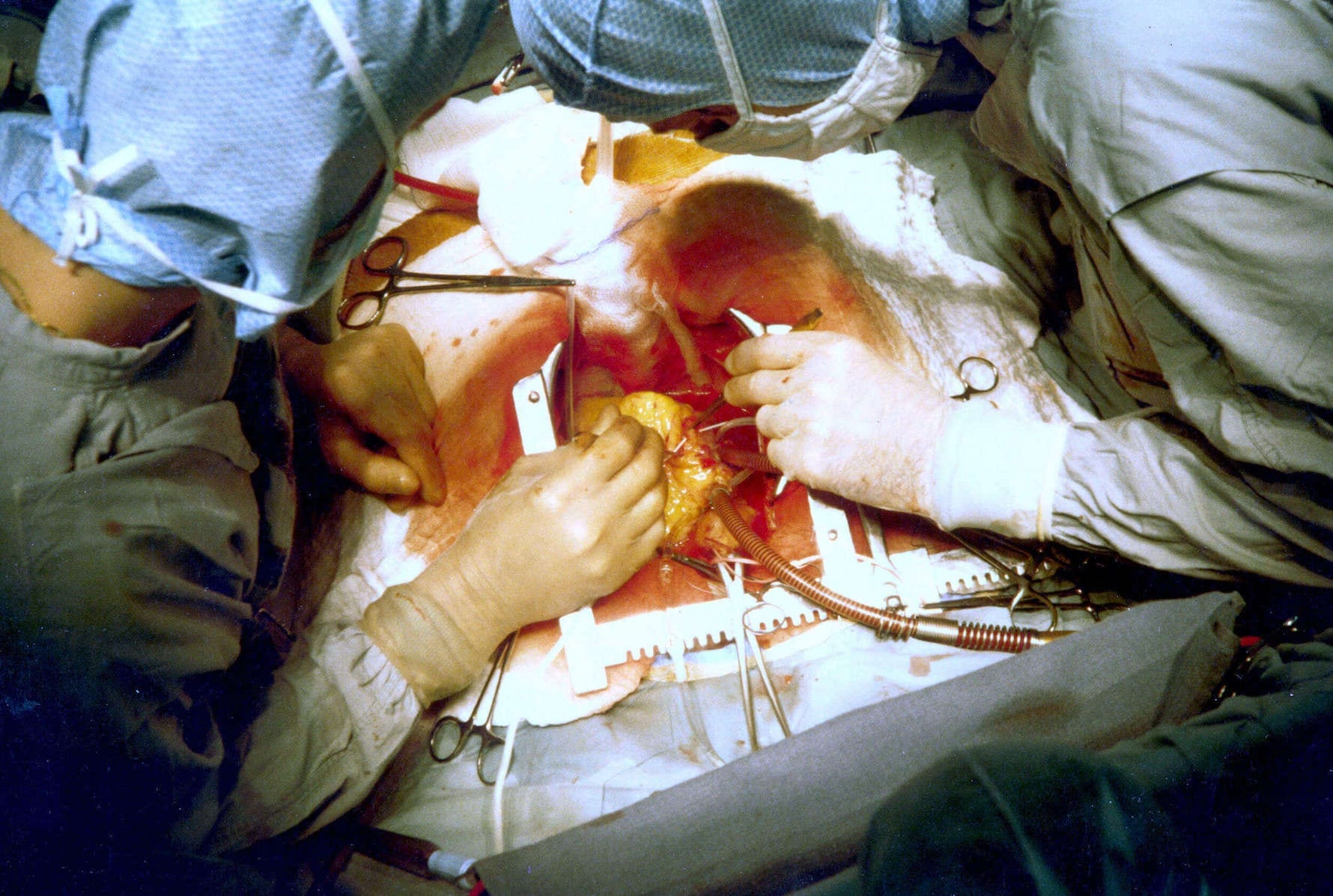

One of the critical operations that a heart surgeon performs is to construct a fresh source of blood supply to the heart before it is too late. As a young cardiothoracic surgery resident, watching this “bypass” operation for the first time was unforgettable. The efforts that go into this operation are nothing short of extraordinary. The surgeon must first divide the chest bone with a saw. The patient is placed on a heart-lung machine the heart is drained of blood, and chemicals ultimately stop it from beating. Only after all of these steps have been successfully taken is the surgeon given a brief window of opportunity to suture a new source of blood supply to the heart by connecting two tiny arteries, each spanning only a millimeter across.

“This is the life-saving part of the operation,” the attending surgeon said to me. “Everything up to this point would be for naught if we failed in the next five minutes.”

I nodded and waited quietly for what was to come, struck by the palpable gravity of the task before us.

This is one of the reasons why cardiothoracic surgery inspired and enticed me in the first place. I wanted to bear the most critical responsibilities during times of my patients’ direst needs, even if it meant dedicating my whole life to honing these skills. Although the training is longer and more arduous, the privilege we are entrusted by society to operate on their hearts is profoundly humbling.

The prospect of holding that responsibility is also terrifying. From where I stood, I could hardly make out the contours of the arteries the surgeon was sewing. In his steady hands, at the tip of a slender golden instrument, was a needle thinner and lighter than hair. His eyes were riveted to the surgical field, planning out the life-saving choreography that would soon take place.

One day, I will be the surgeon wielding the needle that either extends or shortens someone’s life and there will only be a single opportunity to get it right. How would I carry the weight of a life in my hands or cope with the consequences of my actions if I were to fail? From where I currently stand, the challenges ahead appear insurmountable.

Whenever I feel intimidated, I try to remind myself that the building blocks of my dreams are already well underway. I have been walking this path for many years, steadily and patiently preparing for the moment when I will wield the needle. The people around me encourage and support me selflessly. The operation, figuratively, was already happening before my eyes. When my parents made the decision to give up their home in South Korea to immigrate to America so my brother and I would be able to pursue our dreams, they were dividing the chest bone and opening the narrow window of opportunity. When my mentors accepted me into the cardiothoracic residency program, they were placing the patient on the heart-lung machine and rendering the heart still.

Now I stand before the heart as I begin residency, in my hands the tools and the opportunity afforded by decades of hard work, preparation, and help from others, with one chance to get it right. I am already in the coronary moment of my life, and with each passing day it all seems more within my reach. Whether we realize it or not, many of us are already living out these coronary moments, growing little by little each day in the hope of overcoming challenges that seem insurmountable at first.

Some challenges we face as individuals and as a society are titanic and seem to offer little hope. As Robert F. Kennedy said after Martin Luther King died, the “mindless menace of violence in America . . . again stains our land and every one of our lives” (Martin). News of civilian slaughter in our communities afflicts and degrades us all. These matters may not have easy solutions and seem too deeply ingrained in our society to fix. The scale of the challenge can paralyze us into inaction. Instead of hiding from challenges out of fear or intimidation, we can begin to prepare for them diligently, in small but steady strides, so that one day we may face them as the very best versions of ourselves.

The surgeon did not hesitate before the arteries. With sutures so thin they are nearly invisible to the naked eye and so light they appear to float, the surgeon began to sew the openings together slowly and meticulously.

“Every needle entry and exit has to be perfect here. Too loose, it bleeds. Too tight, it doesn’t allow for blood flow. You have to get it right because we only get one chance to do it right.”

I nodded, holding my breath as the edges of the arteries gently lifted off the tissue under the gentlest forces. I watched the new artery slowly glide down to the heart over tracks of shimmering spindles and meld together with each pass of the needle. Once connected, I could see it begin to deliver fresh blood to the heart, filling it with a pinkish hue, now beating more robustly than it had before. It was a success.

Before I could ask to take a look at the life-saving connection one last time, the surgeon began to close the chest by bringing together the bones with steel wires. In just a few moments, the brief, narrow view of the beating heart and the critical task it entailed disappeared from our reach.

Be steady, my hands, my heart. With humility and preparation, we will get it right when the moment comes.

References

- Martin, Z. J. (2009). The mindless menace of violence: Robert F. Kennedy’s vision and the fierce urgency of now. Lanham: Hamilton Books.

JASON J. HAN, MD, is an integrated cardiac surgery resident at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. His clinical interests include the role of mechanical pumps and heart transplantation to treat end-stage heart failure. He is also an avid writer, who enjoys reflecting on his experiences and pondering the bioethical challenges of these life-altering therapies. He writes a column for the Philadelphia Inquirer, and has published in STAT news, The Living Hand, and other academic outlets.

Leave a Reply