Ian Williams

Wales, United Kingdom

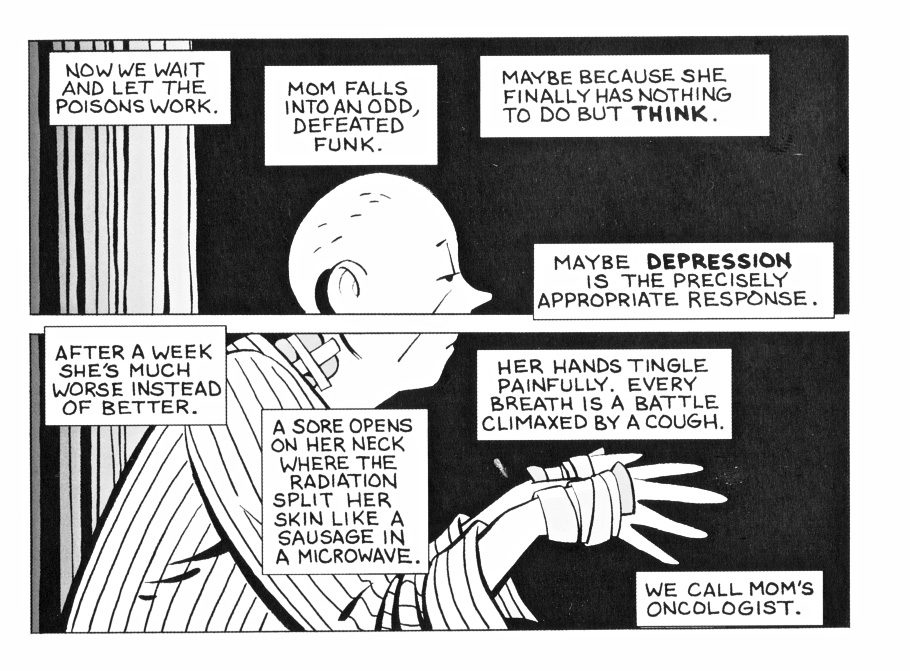

Mom’s cancer by Brian Fies

Introduction

In case you have not noticed, graphic novels have been cropping up in literary reviews that would have previously been the reserve of prose. Thanks to the UK broadsheet newspapers, which have been championing the graphic form for a good 10 years or so, a distinct genre of autobiographical comics has emerged. Autobiographical comics grew out of the underground comics of the sixties and seventies where authors documented their neuroses, perversions, or experiments with sex and drugs. Developing from these unusual influences, many modern comics have foregone the superheroes of the past “in favor of the particularized and unglamorous common man or woman” (Hatfield 2005:111).

While this tendency to document the mundane began at the more radical end of comics publishing, it has gradually evolved to include memoirs that deal with illness and suffering. Calling this distinct sub-genre graphic pathography in the British Medical Journal, Green and Myers (2010) have described how comics can be used in a “novel and creative way to learn and teach about illness.” Similarly, while undertaking an MA in medical humanities, I discovered within comics a volume of relevant material that demanded some sort of academic consideration from scholars of narrative, healthcare, and art. Christening this area of study Graphic Medicine, I began to briefly review works of interest on a website dedicated to the topic.

Portrayals of suffering

Binky Brown meets the Holy Virgin Mary by Justin Green

Mom’s Cancer by Brian Fies first drew my attention. Fies, a cartoonist and science writer from San Francisco, had forayed into comics by way of an anonymous online strip about his mother’s experience of the healthcare system. The tale of an ordinary middle-class family, Mom’s Cancer depicted their struggle to accept their mother’s illness while navigating the fragmented healthcare system treating her. Holding a mirror up to the caring profession, the book highlighted some of the system’s inadequacies as well as the precarious nature of cancer treatment itself. Humorous, empathetic, yet provocative, it struck a chord, and many people contacted Fies to tell him how much the strip helped them. After winning an Eisner Award for best online strip, it was published in 2005 as a graphic novel.

Other works examining a similar theme are Marissa Marchetto’s Cancer Vixen, Harvey Pekar and Joyce Brabner’s Our Cancer Year, and Stan Mack’s Janet and Me. Each highlight the frustrations of navigating oneself through the difficulties of cancer treatment: weighing up contradictory opinions and plans, dealing with insurance companies, and negotiating one’s care when most vulnerable. Illustrating an important function of comics—given the genre’s radical cultural background—these books are well placed to critique the functioning of healthcare systems.

The proliferation of image-based media has ensured that representations of health, illness, and disease assumed a prominent place in western societies (Lupton 2003:79). Comics—which refers both to the physical objects and their attendant philosophy and practice—has played its part in this process. A gradual easing of censorship over the twentieth century and greater popular acceptance has lead to the abundance of disease images in the mass media. Underground comics makers were among those who took control over their own illness stories. Frequently cited as creating the genre, Justin Green’s 1972 neurotic memoir Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary described his torment in suffering a religious form of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (See Fig. 2).

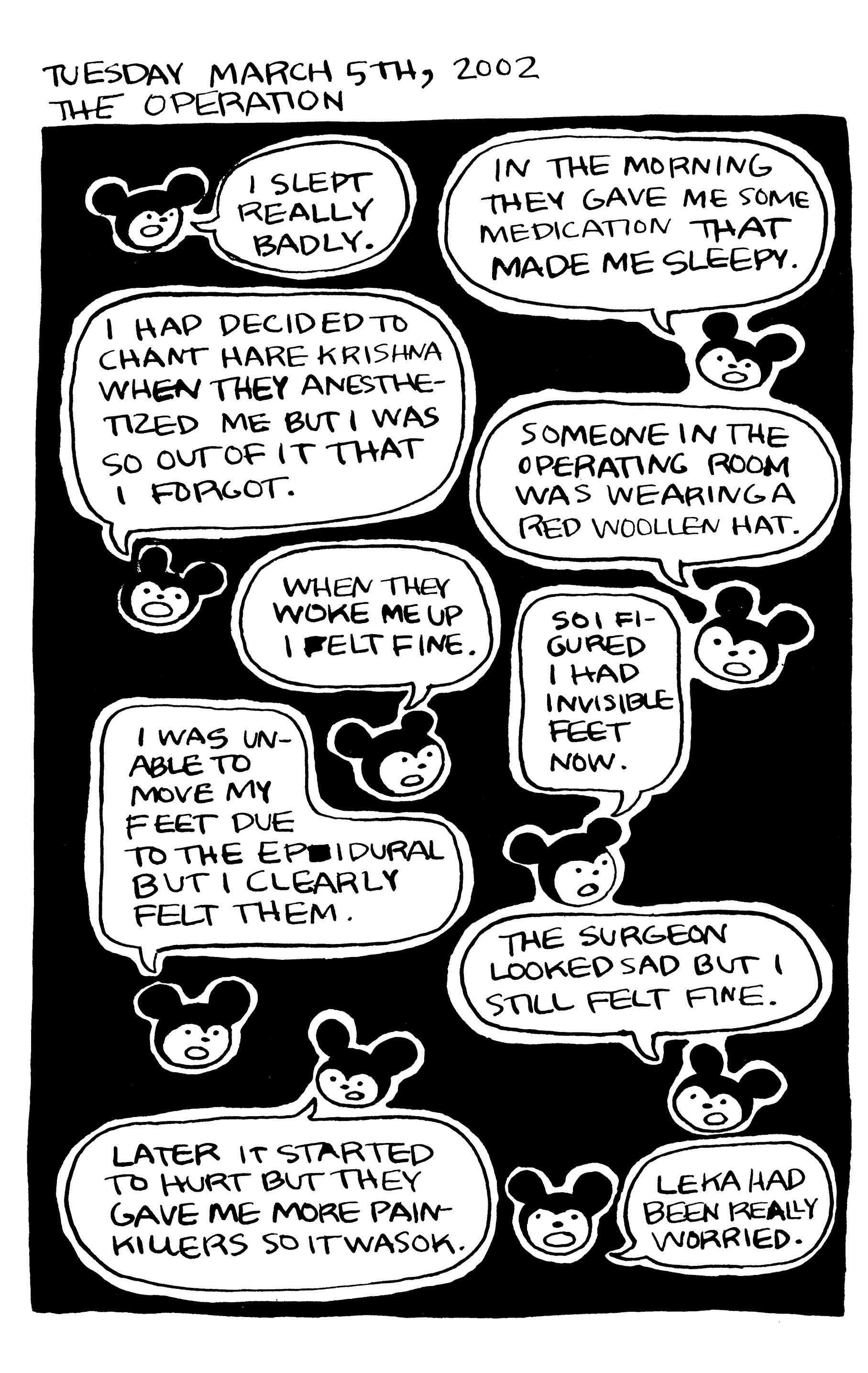

I am not these feet by Kaisa Leka

The iconography of disease

The depiction of illness influences the perception of illness, which can change the illness experience for others. Comics artists exercise considerable personal power through the publication of visual illness narratives. The Finnish comics artist and politician Kaisa Leka subverts the usual portrayal of the sick body in her graphic novel I Am Not These Feet (2008), which documents her decision to have her congenitally malformed feet amputated and replaced with hi-tech prostheses.

Portraying herself as a mouse, she employs the anthropomorphic animal, a traditional comics device that Art Spiegelman most notably used in his Pulitzer-winning Maus. Freed of the necessity for accurate self-representation and associations with the human form, anthropomorphic animals allow for the reconsideration of human conduct in a different light. Thus, Leka, by objectifying herself in her story, has the power to reframe her illness and her self-concept. The minimalist drawing style serves a similar purpose, allowing us to project ourselves onto the character, identifying more closely with it. The simplified detail of her lower legs and feet—which become a couple of black lines with white loops at the base—also frustrates our desire to see her deformity, allowing Leka to control the distance between author and reader.

While the narrative deals mainly with her recovery from the operation, one is left wondering what sort of deformity prompted her to choose radical bilateral below-knee amputations. Controlling how much information to release, Leka spares or perhaps even withholds from us the emotional details, denying the graphic depictions the reader has come to expect from the genre. Rather than immersing us in a melodramatic autobiography, her restraint draws us in and fires our intrigue (See Fig. 3).

In addition to manipulating the depiction of illness, comics artists use a range of rhetorical visual devices to articulate the feelings associated with the illness, offering a window into the subjective realities of the author and providing companionship through shared experience in a more immediate manner. Illness narrative confirms directly that others have been through a similar catastrophe and, hopefully, lived to write about it.

Ken Dahl’s excellent Monsters (2009) deals with the experience of contracting, and passing on, genital herpes. Managing to be poignant, funny, and savage all at the same time, the comic yields both important clinical and emotional information to the reader. Drawing himself surrounded by a viral envelope that separates his “diseased” body from “normal” society, Dahl (real name Gabby Schultz) skillfully employs visual simile to portray his feeling of isolation after his diagnosis (See Fig. 4). In other passages, he articulates his self-loathing and disgust by picturing himself as transforming into an oozing bag of herpes virions (2009:54) or his frustrated libido, which changes him into a rabid, lascivious dog (2009:70-71).

The use of comics

Monsters by Ken Dahl

Comics can be used in a number of ways within the healthcare setting. They have been used for a number of years in patient information leaflets, with varying success, often aimed at demographics to whom the image/text combination will appeal. Medikidz has recently produced high quality children’s comics that explain various illnesses, treatments, and procedures. Similar approaches have been used in sexual health, with comics such as Love S.T.I.ngs (2009) by comics artist ILYA aiming to educate young people about safe sex. As the focus of literacy has shifted from the textual towards the visual among youth, these approaches take advantage of the popularity of comics, manga, and visual media among young people (Eisner 1996:3).

By reading comics, health professionals can also facilitate reflection and understanding of issues that might not have been previously considered. Reading groups might find graphic novels an effective way of opening up discussion on difficult, complex, or taboo topics such as child sexual abuse, a theme dealt with head-on in Phoebe Gloeckner’s A Child’s Life (2000) and Debbie Drechsler’s Daddy’s Girl (2008).

Professional reflection can also be facilitated by making comics. For the last three years Michael Green of Penn State University Medical School has taught an elective course to fourth-year medical students entitled Graphic Storytelling and Medical Narratives. The course was developed to demonstrate how comics can be used to effectively communicate complex medical narratives and to teach medical students to depict own stories and experiences in graphic form. Currently working on a full-length work, Taking Turns, A Medical Tragicomic, MK Czerweic has spent the last 20 years drawing comic strips that depict her experiences as a nurse in an HIV/AIDS unit at the height of the epidemic. I also make comics about my experiences as a general practitioner in rural Wales under the nom de plume Thom Ferrier. In constructing the strips, I am often forced to examine the subtleties of the story which, although fictionalized, often have a basis in a real life experience.

The cutting edge

Autobiographical comics come from a radical background that respects self-publishing and small scale circulation. In fact, small press and self-publishing fairs—where unpolished and unfiltered narrative dominates—represent the “cutting edge” of comics, even though the vast majority will never see professional publication. Interesting comics are also found online. Some comics of note include: Everything You Never Wanted to Know About Crohn’s Disease by comics artist, illustrator, and publisher Tom Humberstone; Better, Drawn (a collection of short strips about mental health issues) curated by Simon Moreton; and The Walk by Ryan Pequin, a Canadian artist who described his experiences working at a care facility for four mentally challenged men (Squier 2008:140).

Comics offer an engaging, powerful, and accessible method of delivering illness narratives. It constitutes, as Susan Squier has asserted:

[a] hybrid genre—a combination of word and image, narration and juxtaposition—the . . . graphic narrative has the capacity to articulate aspects of social experience that escape both the normal realms of medicine and the comforts of canonical literature (2008:130).

The medium has and will continue to represent popular cultural conceptions of medicine. The quality and quantity of modern depictions of disease not only provide a rich source of knowledge about the experience of illness, but, being such, demand scholarly attention.

References

- Brabner, J. & Pekar, H. (1994) Our cancer year. New York: Thunder Mouth Press.

- Dahl, K. (2009) Monsters. New York: Secret Acres.

- Drechsler, D. (2008) Daddy’s girl. Seattle: Fantagraphics.

- Eisner, W. (1996) Graphic storytelling and visual narrative. Paramus NJ: Poorhouse Press.

- Frank, A. (1997) The wounded storyteller. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Fies, B. (2006) Mom’s cancer. New York: Abrahms.

- Green, J. (1995) Justin Green’s Binky Brown sampler. San Francisco: Last Gasp.

- Green, M. & Myers, K. (2010). Graphic medicine: use of comics in medical education and patient care. British Medical Journal, 340,574-577.

- Green, M. (n. d.) Beyond superheroes: comics as a new genre for medical storytelling. Retrieved from the Penn State Hershey website at: http://www.pennstatehershey.org/web/alumni/beyond-superheroes.

- Gloeckner, P. (2000). A child’s life and other stories. Berkeley: Frog Ltd.

- Hatfield, C. (2005). Alternative comics—an emerging literature. University press of Mississippi

- ILYA. (2009). Love S.T.I.Ngs: a beginner’s guide to sexually transmitted infections. London: Family Planning Association.

- Leka, K. (2008) I am not these feet. Helsinki: Absolute Truth Press.

- Lupton, D. (2003) Medicine as culture. London: Sage.

- Mack, S. (2004) Janet & me: an illustrated story of love and loss. New York: Simon and Schuster Paperbacks.

- Marchetto, M.A. (2006) Cancer vixen. New York: Knopf.

- Spiegelmann, A. (2003). The complete Maus. London: Penguin.

- Squier, S.M. (2008) Literature and medicine, future tense, making it graphic. Literature and Medicine Vol 27.2 pp124-152.

IAN WILLIAMS is a physician, medical humanities scholar, and comics artist based in North Wales, United Kingdom. He runs the website Graphic Medicine and lectures on and writes about comics and medicine, having co-organized three conferences on the subject.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2012 – Volume 4, Issue 1

Leave a Reply