Irene Martinez

Chicago, Illinois, United States

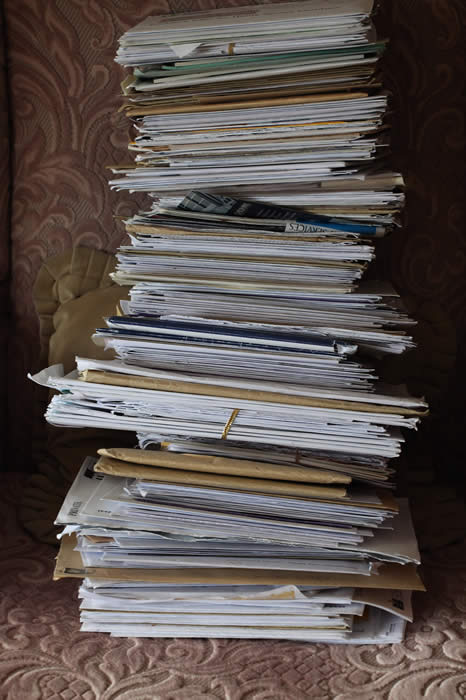

When I arrived at the clinic, I was already behind schedule. I got up at 5:30 to get ready, but with my daughter’s end of the year school trip made things more complicated. I was already rushing when I got to the clinic, feeling agitated, my stomach tightened, yet high-spirited and hopeful. I looked at the pile of charts waiting, which I reminded myself were patients waiting to be seen, and not just charts. I counted three. Not so bad, I thought. I took a deep breath. “I can catch up,” I told myself.

For me, catching up means running, holding my breath, feeling my muscles tense. My right arm becomes like iron; my hand holds the computer mouse too high. My mind speeds in all directions, one thought focusing on what I am doing and others caught in future actions, or regretting past ones. I chastised myself for getting behind, but I was just too tired yesterday to review lab orders after dinner.

My first patient was Maria, whom I know well. I’ll get through with her quickly, I thought. But I was wrong. She does not show up to the clinic often, but when she does, she is good at detailing all of the very big and very little problems she is having. I reminded myself to breathe and we went through them one by one, addressing her different needs and writing those hateful electronic referrals for different specialists—the podiatrist, ophthalmologist, mammogram clinician. And then there was the endless list of medications to renew.

When I finished with Maria, I was sure that that pile of charts had grown. I walked into the adjacent room to see my second patient, who was waiting, seated. She had on a becoming “Oprah” style wig with a flip at the end and a nice band. They can make a woman look a lot younger. Her eyes looked larger through her reading glasses. Though her face was skinny and her skin was a little pale, she was elegantly dressed. As I entered the room and greeted her, she blurted out, “Oh doctor, since I saw you last time I had a stroke!”

Wow, I thought. That is a biggie. When? How? She answered slowly and articulately, but with a small tremor in her voice. I did not notice any motor or speech defect. Meanwhile, I was looking at her chart with one eye—ahh . . . she has diabetes, high cholesterol, high blood pressure—and with the other eye, I was listening, responding, rushing.

“Where did you go when it happened? What did they tell you?”

“Well,” she said, “they said I had had a little stroke; they found it on the scan.” I was thinking it must have been very little because I was not noticing any gross problem.

“What exactly happened?” I asked her again.

“I wasn’t feeling well,” she said. “I had a bad headache for three days so finally I went to this hospital where they did the scan, told me I’d had a stroke, and gave me this medication.” She handed me a bottle. “Plavix,” I read. Okay, now I need to call the help desk to have them approve the medication.

“What else did they do for you? Did they look at your neck? At your heart?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “To tell you the truth, I don’t know what happened until I came home. I just couldn’t believe that something like this was happening to me.”

“Well, did you feel any weakness or numbness in your body? Did you have any difficulty speaking?”

“No . . . I don’t quite remember.”

I looked at her again. “You look fine to me now.”

She immediately relaxed, leaned back, and smiled. “Thank you, Doctor, for saying this.” But in an instant, her smile fled and her fear became tangible again. “I couldn’t believe this was happening . . .” she repeated.

“Let me see some information here,” I said, looking into the computer, my hand holding the mouse, twisting my body to read the computer without completely turning my back to her. I cursed whoever put this system here; they certainly didn’t bother to think about body language. It is especially awkward since we now have to look at the screen for everything. Apparently, I’m supposed to develop a third eye in the back of my neck. Computerized health care, I think, was not part of the medical oath I took when I graduated from medical school.

Back to the task at hand: reading her labs, I saw that her diabetes had gone bad over the past 2-3 months. What is going on? I asked myself. The stress of the stroke? What could have caused it? Also, her blood pressure was higher than usual today. I was thinking through all this, remembering to call for the Plavix approval and to schedule her for a neck ultrasound. I turned around to share with her my findings and told her that maybe this was a warning sign, that we would need to be more vigilant, pay closer attention to decreasing her stroke risk, lower her blood pressure.

Mouse in hand, I asked her again how she felt about all this, at the same time mentally adding to my “to do” list, when she said, “I don’t feel loved.” Her left hand was pointing at her heart, her eyes wide open, Oprah wig impeccably in place. But she didn’t look lively now.

Wow. All the rushing stopped; time quieted. I looked into her eyes, “What did you say?”

“I don’t feel loved,” she repeated, shaking her head and leaning her shoulders forward, as if trying to get rid of the thought and keep it inside.

My body and voice softened, the mouse and computer forgotten. I turned toward her. “Tell me about it. Why do you say that? Do you live alone?”

“No, I live with my children . . . but I feel alone.”

“Have you told them how you feel?”

“Yes, but they say it is my imagination. That I should be grateful.”

She continued to talk. I asked her about depression, whether she cried often. She said she did. Then she mentioned not having had a male friend for a while. I asked her about feeling pleasure, whether there were activities she found pleasurable. Yes, she goes to the casino, to church. Yes, she feels pleasure. But not loved.

Neurology called back to approve the Plavix. I pictured my other patient fuming in the next room because I had taken so much time with this one. I asked the nurse to teach her about insulin use, and returning to the blood pressure prescription, I discovered that she had run out of medication two days ago. I begged her not to let this happen again and explained to her the risk. Her physical showed nothing pertinent. Neuro and heart okay. She just didn’t feel loved, and it was supposedly in her imagination.

I sensed I was rushing again. “Please come and see me next week,” I said. “We have to make sure your blood pressure is okay and see your blood sugar response to the insulin.”

After half an hour or so I was in the hallway making a phone call for another patient. She walked toward me, giving me a kiss on the left cheek. “Thank you,” she says. She squeezed my hand and we looked at each other.

“Come back next week,” I said. “We’ll talk about being loved.”

IRENE MARTINEZ, MD, is a physician, clinical educator, wellness and human rights activist, visual artist and writer. For nearly 30 years she has worked at Cook County Hospital (now John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital of Cook County). Dr. Martinez received her degree in medicine from the Cordoba National University in Argentina, and completed a Clinical Ethics Fellowship at the University of Chicago. She has developed innovative clinical programs enhancing the role of resilience in human dignity and wellness. With the support of the IHC, she ran a seminar entitled, “Literature and Medicine” from 2007– 2010. Dr. Martinez’ work underscores the reality that expression is therapeutic, and that the arts are the soul of expression.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Winter 2014 – Volume 6, Issue 1

Leave a Reply