Hugh Silk

Massachusetts, Worcester, USA

|

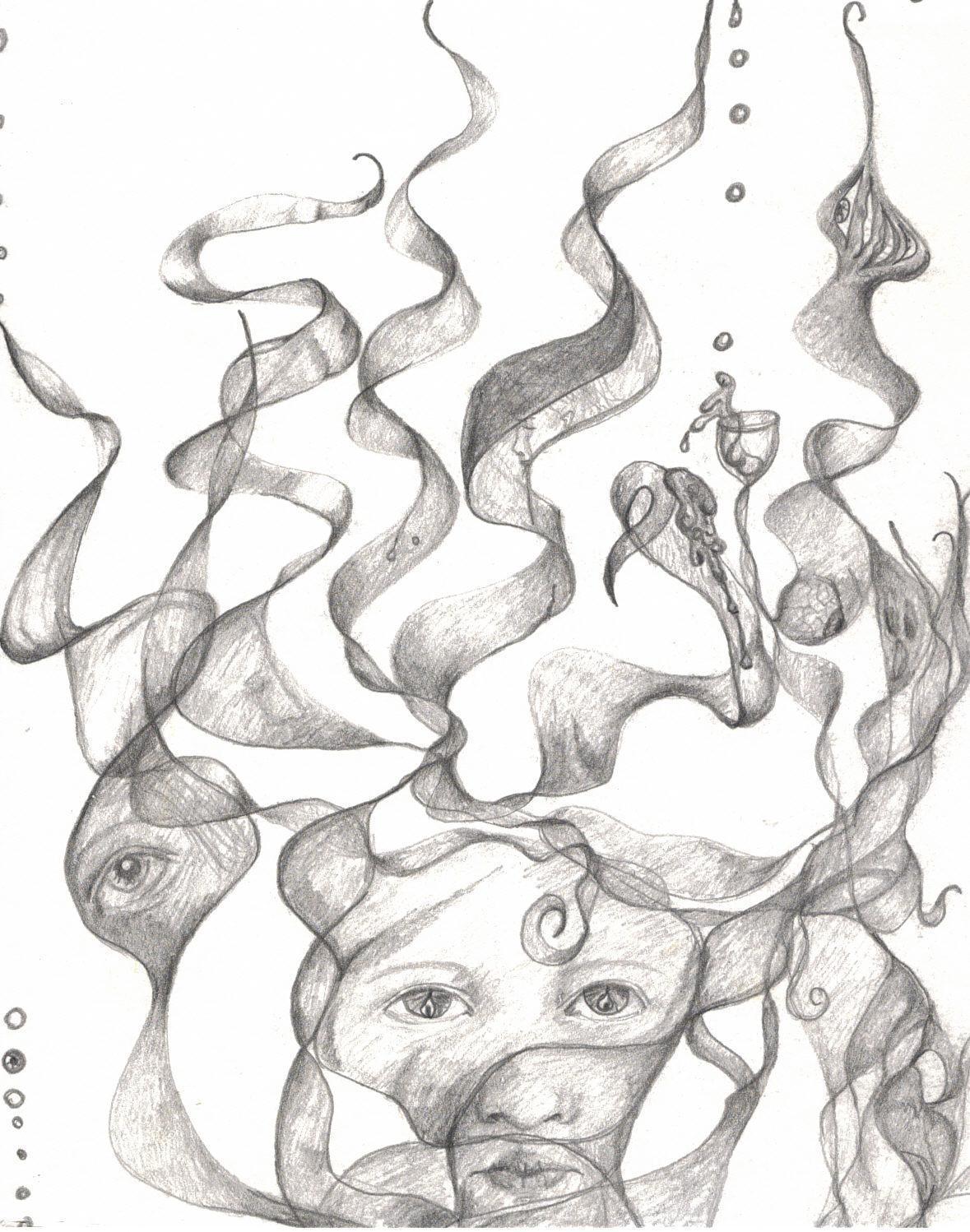

| Entangled Anjali Dhurandar, Pencil 8” x 10” |

“Hi, Kate. Good to see you. How are you?”

“I’m nervous, doc, so please tell me everything right away.”

Her eyes were focused intensely on mine. It was clear my small talk and pleasantries were unwanted, even before I shut the exam room door.

“Let me start by telling you that all the tests were normal—blood work, heart ultrasound, EKG, and the exercise test. The monitor you wore for a few days showed that even when you feel your heart acting strange, the beats and rhythm are all normal.”

Judging by her expression, this was not the answer that she was looking for.

“That’s good news, Kate. Normal is good.” I tried to smile assuredly. My professor in medical school had noted that I was smart and hardworking but needed to smile more to connect with my patients. It was a comment that has stuck with me, and I always make the effort.

“Then, what is it? Why does my heart flutter? You say it’s normal, but it doesn’t feel normal. I know it’s not right to race like that.”

During her last visit, I had inquired about everything that might account for the flutter: use of caffeine, cocaine, over-the-counter medications, family history of arrhythmias. There was nothing.

“Kate, I’m a pretty good physician. I have asked you a lot of questions about your heart; I did a thorough examination—that’s usually where the answer lies. I did those tests just to be sure . . .” I paused, “I’m sorry, but maybe I didn’t give you enough time during the last visit to . . . just tell me your story.”

My voice drifted off. She was looking away. Was she avoiding the real issue here? I knew Kate fairly well, but maybe she didn’t completely trust me. I wondered if it was the awkwardness of my being a young, male physician and her being a pretty, young woman sitting here alone with me behind closed doors. It always struck me how the intimacy of the doctor/patient relationship could mean something totally different in another setting.

“What else could it be? I really hope . . . I need to be better.”

“Kate, you’ve heard me say this before: I am only here to help you. You know your body better than I do. Physically your heart is okay. I am here to listen if you need to tell me more. What in your life could be hurting your heart in this way?

The gaze that had been looking at me, searching for answers, now turned inward. Her eyes filled with tears. “You already know,” she replied. “You took care of me when I needed an abortion. You were so nice when I couldn’t even be nice to myself. I’m not sure how it happens. I’m good-looking, smart, and have a solid job. I’m a nice person. But I end up with losers who don’t treat me right.”

I offered a tissue, and she gratefully accepted.

“Can you damage a heart with all of that in your life? I mean, can having your heart broken that many times actually cause it to not work right? I know it sounds funny, but with all those tests being okay, could my problem actually be caused by how badly I’ve been treated when it comes to love?”

She looked to the ceiling. Maybe to God? I looked there too. We both took a moment to breathe. This scenario was never covered in my cardiology elective. My wandering mind recalled seeing an advertisement for a new cardiology clinic with the slogan “We mend broken hearts.” What would they do for her?

“I believe it can, Kate.” Her gaze returned to me. “The longer I practice, the more I believe that we understand 1/10th of one percent of how the body works. There is so much we haven’t discovered yet.” I paused to be sure she understood. “I think you just figured something very important out, and I believe you more than any expensive study. Maybe just coming here has helped.”

The tears kept falling. Regretting the mistake from our last visit, I resisted the urge to check my watch. There was something else she was not telling me. I prodded, “I have to ask one more question: What are you most afraid of?”

The crying ebbed. I could almost see the burden lifting as she spoke, “My mom did have a heart attack, but I didn’t tell you this before: she swore my alcoholic father had wounded her heart from all the misery he caused her. She told me not to talk about it. I guess I always hoped it wasn’t true.”

Earlier in my career, silence made me uneasy. Now it was my friend. There was no right answer here. I nodded, offered another tissue, and tried to offer what comfort I could. Silently I wondered, “Should I send her to a psychologist? Was this enough for today?”

She stood to leave. “I feel a little better already. I think I needed to tell someone about my mother. I needed to be honest with myself.”

With a final nod, I advised, “Nobody can hurt your heart if you protect it. Only let those who respect you near it. I can’t put that on a prescription pad, but I think it’s important.”

“Me too.” Her smile was surfacing. “Thanks, doc.”

“Thank you for sharing, Kate. It means a lot to me.”

And she was out the door. I sat there for a moment. My nurse, Barb, poked her head in to be sure I was alright. “Everything okay?”

“Yeah, I’m just sitting here trying to figure out what I just did. I simply offered Kate some attention. Now I am wondering if that is really enough. We have all this science and technology, but in the end it comes down to the two of us sitting here for a few minutes making a connection.”

Barb laughed and shook her head knowingly. She had heard it before and would hear it again.

The above story is fictional. The names, events, and characters are imaginary, not real. Any resemblance to real persons or events is coincidental.

Artist’s statement

The illustration tells the story of a young woman. Outwardly, she displays a solemn face, yet internally she struggles and feels burdened by memories, anxieties and inadequacies. The ribbons represent her internal thoughts and emotions and are meant to portray her feelings of disconnection and confusion.

HUGH SILK, MD, MPH, FAAFP, is a family physician at Hahnemann Family Health Center/UMASS Family Medicine Residency in Worcester, Massachusetts and is a clinical associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Hugh moderates a weekly listserv of clinical success stories written by family doctors and learners, runs the humanities in medicine workshops for the residents, and is an active member of the medical school’s Humanities in Medicine Committee. He has also taught undergraduates about literature and social reflection at Harvard University.

About the artist

ANJALI DHURANDHAR, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of medicine and associate director of the Arts & Humanities in Healthcare Program at the University of Colorado, Denver. She studied studio art in college and after residency, completed a fellowship in medical humanities and bioethics. She provides primary care to the underserved and enjoys teaching and participating in all forms of the creative arts.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Fall 2011 – Volume 3, Issue 3

Leave a Reply