Gregory O’Gara

New Jersey, United States

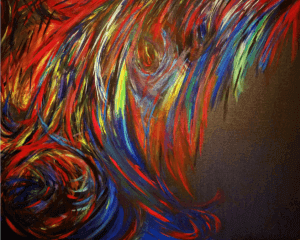

Turbulent Souls, 2017

Oil on canvas

Private collection

The first Sunday in December was a typical winter day; cold but clear, leafless trees, overcast sky. It was the kind of morning I dreaded as a child, having to get out of bed and go to the 11am mass at St. Margaret’s, no time to relax and watch a TV show with my brother. After church we would visit my grandmother at Soundview Nursing Home in the Bronx. In 1979 there were no private rooms, pastel colored walls, or hallways canvased with white nursing stations. The corridors were covered in a yellow-beige ceramic tile, the kind you might see inside the Lincoln Tunnel. I remember my father losing his temper at a middle-aged nurse who simply called his mother “O’Gara.” It seemed dehumanizing.

Most patients were organized in large open rooms of twenty, lying in a regimen of linear cots adorned with golden faux-wood end tables and IVs. There were no privacy curtains. The open expanse smelled like a mixture of body odor and cleaning fluid.

There were haunting echoes of pain and loneliness that moved from corner to corner, like a three-dimensional trinity of physical, spiritual, and psychological suffering. The cries went mostly unattended; even the most compassionate staff could become empty shells in the midst of the perpetual wailing. The experience scared me at the age of fourteen.

But now, on this first Sunday of December, I was forty-one and heading to Stamford Hospital to visit my mom, who was in the last stages of pancreatic cancer. The parking lot was large and haphazard as it encircled the brick buildings with no particular symmetry. The surface needed repaving. Cars dotted the boxed yellow spaces as if they had been abandoned. I walked through the large glass entrance and around a maze of corridors to the cancer pavilion. I pressed an over-sized elevator button to the third floor. Hospital elevators and hallways are large when they are empty. It made me feel exposed. There should have been doctors or a nurse wheeling in a patient to fill the space. The door opened and I walked to the room.

Mom had lost so much weight. A constant drip of IV morphine addressed the pain, but I think it had lost its effectiveness. Her vomiting had forced the nurses to insert a feeding tube with a liquid food mixture. It disturbed me to see the tube inserted into her nose and down her throat. To speak to her, to look into her eyes and see her face, I had to stare at the tube. It was made of a barely flexible translucent plastic. Periodically it would pulse with a dark gel that looked like blood. Sometimes the flow would change direction.

I could not understand why the feeding tube was not inserted directly into her stomach. A doctor said it would be a difficult procedure, and I suppose they did not think she would live much longer anyway. They were correct. She would begin dying that evening after I left.

She was staring at the TV, but turned to see who had come in. I gave her a kiss on the cheek and felt embarrassed to ask her how she was doing. But I did. She smiled gently and said she was “ok.” I pulled up a chair next to the bed and looked around. A month or two earlier my children had drawn crayon pictures with rainbows and flowers that now seemed out of place. Many of them said, “Get well Grandma, we love you.” Normally I would smile seeing their seven- and ten-year-old drawings, but today everything was gray and death felt inevitable. I pulled closer to her and my knee touched a medal of St. Jude on the bedrail. It was wrapped firmly on the silver bar, held in place by a circular twist of scotch tape.

Mom asked if I could adjust her pillows and raise the mechanical bed so she could sit up. This was sometimes an awkward task because the jumble of cables attached to her body would become tight as they stretched upward. Sometimes an IV would detach and set off an alarm. When that happened, a nurse would slowly respond and reinsert it. But that too became difficult because she was dehydrated and frail, her veins collapsing and body bruised from multiple needles. The top of her hands had taken on bruises as well, and had turned the same shade of purple as the liturgical vestments I used to see in church. Life begins with movement. I had a memory of running through a park sprinkler when I was six. Now movement caused pain and tribulation.

Only weeks earlier, Mom was more alert, sitting up, and would greet me with a hug and a smile. Pulling me close, she said, “Greg, we’ve been through worse and we’ll get through this.” Those words hit me hard. My childhood was asphyxiated by her relationship with my father, as she was consumed with her own emotional and physical preservation. This left little time for her to attend to her children’s needs, especially those of comfort and safety. When we were teenagers, she became somewhat alienated from us, perhaps ashamed. This ran against every fiber of her deeply sensitive maternal instinct. It devastated her—and us. So I knew what those words meant, “We’ve been through worse.” I dropped to her side, put my head on her bosom, and cried. No words between us. That was the only time since childhood I had ever cried in my mother’s arms.

As the disease progressed, she had deteriorated terribly. Now the tube was all I could see. As she sat up, she could see it too. The drugs had made her delirious, distant. As the dark liquid pulsated inside, she began to swat the air around her nose, asking me to get the flies away from her face. I tried to explain it was just a tube, but she insisted there were flies. After several minutes of calm, she would repeat herself. Then she began to pull the tube out of her nose. I calmed her again, held her, calling for a nurse who gave her a sedative. The nurse explained that the night before they had to restrain her arms to get the tube in. Mom had removed it twice, pulling it out of her nostril, up from her stomach and out her throat. The nurse said they left the restraints on overnight. Restraints on the arms of my mother? I drifted away, unbelieving, powerless, stunned. Where was mercy? What had really changed since my childhood visits to Soundview to see my grandmother?

Everything seemed to be in contradiction in that moment. I felt disconnected. Language, communication, expression, touch, all became a knotted patchwork. Nothing fit. As I left, I recalled the words of Psalm 22: “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me? why art thou so far from helping me . . . O my God, I cry in the day time, but thou hearest not; and in the night season, and am not silent. But thou art He that took me out of the womb: thou didst make me hope when I was upon my mother’s breasts.” (Psalm 22 1-2, 9 KJV)

The next day I walked into the room where my brother stood on one side of my mother. Her sister stood on the other side, pale, gaunt, wondering if there would be closure to the suffering. I looked at the cylindrical pump standing next to the bed. For a second, the cylinder would come to rest, compressing itself into a brief moment of silence. I thought the room became quiet, perhaps peaceful in that moment. And then the pump would start again, expanding upward, withdrawing air from her lungs.

I left not knowing whether she still had any life. The nurse said there was no longer brain function. Moving down the hall, I sat on the ground in front of a large window. There was a hot stream of sunlight blazing against my back. It cut through the cold December air outside, heating up my shirt. My brother looked at me from the room. I had left him alone to perform the final act of ending her life.

I waited for a moment and looked across the hall again to my brother, her sister blending into a corner. I don’t remember hearing anyone cry, just the silence that echoed against the walls of the Dying Room. And still the sun burned strongly against my back.

GREGORY O’GARA, is a native of the Bronx, NY. Greg attended high school at the Ethical Culture Fieldston School. His love of writing and poetry grew out of Fieldston’s dedication to classical education and outstanding teachers. Greg obtained a B.S. in engineering and later completed his MBA in finance. His passion for writing further developed as a speechwriter and research analyst in the chairman’s office of PaineWebber (now UBS). He has worked as a corporate strategist for several firms including: UBS, Prudential, TIAA-CREF, and TD Ameritrade. Greg currently resides in New Jersey and enjoys painting and playing the piano.