Roger Paden

Virginia, United States

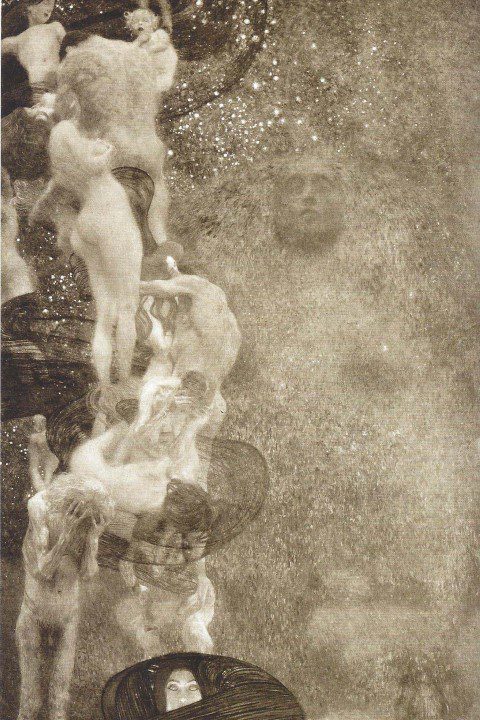

Gustav Klimt

Destroyed by fire in Schloss Immendorf in 1945.

In 1894, Gustav Klimt and Franz Matsch received a commission to create a series of paintings that were to be installed on the ceiling of the Great Hall of the New University of Vienna. Eleven years later, in the midst of an increasingly bitter scandal, Klimt was forced to take back his paintings in return for his share of the commission. This scandal helped complete the aesthetic radicalization of one of Austria’s greatest painters: Klimt had already become the president and founding member of the Vienna Secession, the first—and most celebrated—modern art movement in Austria, but now he would never again accept a commission from the state.

Before this scandal Klimt seemed a talented, if somewhat conservative, decorative painter. He was best known for allegorical paintings that were hung on the walls and ceilings of some of the new buildings lining the Ringstrasse, such as the Burgtheater (across from the University) and the History of Art Museum (a few blocks away). The Ringstrasse is a circle of streets that in the 1860s replaced the defensive walls that had protected the Old City of Vienna. At the time of its construction, the Austrian government hoped that the new urban plan based on the Ringstrasse would create a cultural and political showplace that would help unite the ethnically diverse empire around a more modern culture and politics, and Klimt had already played a minor role in this project.

The intent of this new commission for five large paintings and some lesser supporting paintings was to celebrate the University and its place in the new modern Austrian society.1 Four of the larger paintings were to celebrate the four traditional “Faculties” (departments) of the University. The theme of the entire installation, expressed by the fifth and central painting, was “the triumph of light over darkness,” and the purpose of the installation was both to celebrate the “victory of the Enlightenment over superstition and ignorance” and to memorialize the roles that the various Faculties played in realizing the modern dream of progress through reason and science. Klimt was to paint Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence, while Matsch was to paint Theology and the central thematic painting. This was to have been a fairly standard decorative project and the two painters had proposed some fairly traditional allegorical paintings in which the Faculties would be represented by various triumphant mythological figures; in Jurisprudence, an avenging Justitia with sword raised high would represent the Faculty of Law; in Medicine, Hygeia, a goddess of healing, was to represent the Medical Faculty; and in Philosophy, an all-knowing sphinx would represent the Philosophers.2

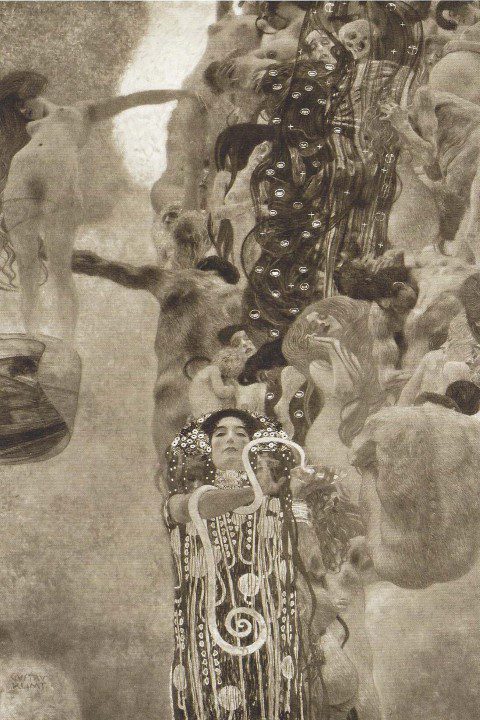

Although our evidence is indirect as Klimt’s three Faculty paintings were destroyed by fire in the closing days of World War Two and all we have of them now are black and white photographs and a color reproduction of the priestess figure in Medicine, by all accounts they were powerful works of art: Philosophy, for example, won a gold medal at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair. But in Vienna the paintings were subjected to intense criticism. Conservative political parties claimed that they were pornographic, but the Austrian government, eager to develop a new form of art to help unify and modernize Austria’s ethnically-divided and backward society, brushed off these objections. More important objections came from members of the Faculties themselves, who claimed that Klimt’s paintings failed to illustrate the agreed-upon theme: not only did they fail to celebrate the Faculties, but in fact they seemed to be highly critical of them. These last criticisms were well-founded and, ultimately, decisive.3

The problem seems to have been that after accepting the commission, Klimt came to embrace Schopenhauer’s pessimistic philosophy of the Will, and this Romantic philosophy conflicted with the more optimistic philosophy of the Enlightenment. In Schopenhauer’s view, the world of “representations” around us is a production of the “Will,” an irrational, but highly creative force that underlies all reality. Human beings, too, are creatures of the Will and, as such, it is our will and our desires, not our reason that forms and controls us. As a result, Schopenhauer argued, while seeking happiness, we are driven by our desires and, given their nature, that goal will elude us:

All willing springs from lack, from deficiency, and thus from suffering. Fulfillment brings this to an end; yet for one wish that is fulfilled there remains at least ten that are denied. Further, desiring lasts a long time, demands and requests go on to infinity; fulfillment is short and meted our sparingly. But even the final satisfaction itself is only apparent; the wish fulfilled at once makes way for a new one; the former is a known delusion, the latter a delusion not as yet known. No attained object of willing can give a satisfaction that lasts . . . but it is always like the alms thrown to a beggar, which reprieves him today so that his misery may be prolonged till tomorrow. Therefore, as long as our consciousness is filled by our will, so long as we are given up to the throng of desires with its constant hopes and fears, so long as we are the subject of willing, we never obtain lasting happiness or peace. It is all the same whether we pursue or flee, fear harm or aspire to joy; care for the constantly demanding will, no matter in what form, continually fills and moves consciousness; but without peace and calm, true well-being is absolutely impossible. Thus, the subject of willing is constantly lying on the revolving wheel of Ixion, is always drawing water in the sieve of the Danaids, and is the eternally thirsting Tantalus.4

Schopenhauer—“the most Buddhist of Western philosophers”—argued that there is only one way out of this trap; willing must cease! And there are only a few ways to bring about the cessation of the will. Guided by a proper philosophical understanding of the Will, we can pursue ascetic practices, savor aesthetic experience, or commit to an ethics of self-sacrifice. Obviously, however, this view runs counter to Enlightenment’s utilitarian notions of progress and the nature of the good life, and contradicts the deepest aspirations and self-understandings of the University Faculties. Given that Klimt was committed to Schopenhauer’s philosophy of life, it is not surprising that his Faculty paintings failed to satisfy the University’s professors. While they might not have fully understood every elements in these paintings—their criticisms focused on such relatively trivial things as Philosophy’s dark background—with Schopenhauer’s philosophy in mind, it is fairly easy to read these paintings and to understand the detailed criticisms contained therein.

Gustav Klimt

Destroyed by fire in Schloss Immendorf in 1945.

Medicine and Philosophy share a common structure which was discussed in the catalog accompanying the paintings’ exhibition in the Secession Building. Both paintings are dominated by a column of human figures. These columns were based on Hans Canon’s Cycle of Life, and there is, indeed, something very naturalistic about them. Not only are most of the figures naked, but they seem to represent various stages on life’s journey: there is a couple embracing, a pregnant women, a woman suckling her baby, men wrestling (over a nearby woman?), a withered old man, and a skeleton. Most of these figures seem to be unhappy, even despairing. This is especially true of the man at the bottom of Philosophy (who, some contemporary wit remarked, must have just been denied tenure). Among similar figures, in Medicine, we see two figures representing disease and death. In front of these columns in each painting are two very intense “priestesses” who stare directly at the audience, as if challenging viewers to contemplate their own life in light of the column of suffering figures representing humanity. Behind and above these priestesses are female figures that were said to represent the Faculties that are the subject of each painting, the remnants perhaps of the triumphant mythological characters in the respective proposal drawings. Both are oddly distanced from the other elements in the painting. Their eyes are closed, indicating perhaps a willful ignorance. The woman in Medicine who represents the profession (a nude that particularly offended Klimt’s conservative critics) is turned away from her column in seeming despair, unable to contemplate the (Schopenhauerian) truth of existence.

In each painting, the dominant, most colorful and sharply rendered figure is the priestess. In Philosophy, that priestess is “Knowledge.” She seems modeled on “Erda,” the all-knowing goddess of the earth from Richard Wagner’s Schopenhauerian opera, Das Rheingold. Like Knowledge, Wagner’s stage instructions has Erda rising up out of the stage, bathed in a bluish light, facing the audience. It is Erda, who delivers to Wotan the Schopenhauerian message that “all things that are – end” and who counsels Wotan to give up the all-powerful ring that he hopes will enable him to control the world and satisfy all his desires. In Medicine, the priestess is said to be Hygeia, the goddess of healing. She stares sardonically at the viewer while offering a snake (an ancient symbol of healing) a drink of water taken from the river Lethe, a drink that legend promises will cause amnesia. This gesture seems to imply that neither doctors nor their patients can face the truth that life is short and full of pain, and that no treatment can appreciably alter these facts. All our patients will die and their deaths will be accompanied by some degree of suffering, whether physical or emotional.

Members of the Faculties of Medicine and Philosophy were correct in their intuitions that Klimt’s paintings failed to carry out the terms of his commission. Far from celebrating the application of reason to life, Klimt’s paintings urged that reason is impotent in the face of the human situation. Thus, instead of offering real solutions to the deep problem of life, the Faculties are shown to be part of the problem. But it would be a mistake to think that these paintings offer nothing but criticism; instead, implicit in both Knowledge’s and Hygeia’s direct probing gaze is a challenge. Behind them the essential nature of life is revealed, as is the impotence of philosophy and medicine as currently practiced, but the priestesses are looking at us: they challenge us to face the truth and to examine our response to it; they raise a question and await a reply. How do we respond to the truth of inevitable suffering and death?

While this question can be addressed to each of us as individuals, in the paintings this question is addressed to us as members of the two professions. It is not difficult to imagine a Schopenhauerian reply. Philosophy must stop being the handmaiden of the sciences. It must reject an ultimately misleading notion of social “progress” and empty, desire-driven, happiness and examine the human situation as it really is, and especially the connection between desire and suffering that colors every aspect of our lives. Philosophy, that is to say, must search for a way out of the cruelly Sisyphean cycle of suffering. The challenge to medicine is more complex and the correct response more difficult to imagine. How shall we practice medicine when we know that ultimately we must fail? Our tools and techniques, useful as they might be in relieving physical pain or in extending life for a few months or a few years, seem to be incapable of addressing the real enemy, suffering. Can we offer anything but “amnesia,” the forgetting of our common human condition? Must we become amnesiacs to practice medicine? Klimt raises these questions, but he leaves it to us to answer them.

Notes

- Carl Schorske, Fin de Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1981).

- Alice Strobl, “Klimt’s Studies for the Faculty Paintings Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence,” in Gustav Klimt: The Beethoven Frieze. Edited by S. Koja. (New York: Prestel, 2006), pp. 27-29.

- Peter Vergo, Art in Vienna: 1898-1916 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1975).

- Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation. Translated by E. Payne. (New York: Dover Publications, 1966), p.196.

ROGER PADEN, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Philosophy at George Mason University. His areas of research include Environmental Ethics and Aesthetics, Philosophy of Architecture and Urban Planning, and Social and Political Philosophy. He is the author of Architecture and Mysticism: Wittgenstein and the Meanings of the Palais Stonborough, the co-editor with David Goldblatt of The Aesthetics of Architecture, and has published over 70 scholarly articles.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 6, Issue 4 – Fall 2014

Leave a Reply