Stephen Martin

Mahasarakham

Art and architecture in historic almshouses provided aesthetic pleasure, improved self-esteem and attended to spiritual need. An example of early Enlightenment philanthropy in the English village of Kirkleatham, Cleveland, provides major humanitarian lessons for the planners of today.

East Cleveland was used to progressive thinking. A remarkable socio-geographical commentary on the area was written for Sir Thomas Chaloner in 1605.1 Chaloner had been educated by Elizabeth I’s chief adviser, William Cecil, and manufactured alum for tanning, dyes and medicines at Guisborough. The report detailed problems such as poverty, gambling, alcohol, and mental illness. Similar issues continue to affect these isolated villages in the present day (author’s professional experience).

Sir William Turner, 1615-1693, was a wool merchant and polymath who bridged Renaissance and Enlightenment thinking. In 1668 he became Lord Mayor of London under Charles II, living through six British monarchs and two Lord Protectors. Turner did much to rebuild London after the Great Fire of 1666. For the last three years of his life he was also the MP for London.2

Turner’s father John3 had settled in Guisborough, later buying Kirkleatham manor. He married Elizabeth Coulthurst of nearby Upleatham. It is likely that Chaloner would have been instrumental in John Turner’s success. Was he Chaloner’s land agent and author of the report, or just a wholesale sheep-shearer? The former fits better in several ways: dates, locality, rare opportunity of advancement, family ethic of social awareness and intelligence. There are also no other competent candidates for that report’s authorship.

As President of London’s Bethlem Hospital from 1669-1693, William Turner introduced the concept of contracted medical salaries. Doctors could then concentrate on the inpatients without going elsewhere for private practice. He presided over the building of the new Bethlem Hospital at Moorfields, London, in 1675-1676. To achieve the best result, he hired the physicist Robert Hooke as architect. Turner was a driven character, giving attention to major projects in quick succession.

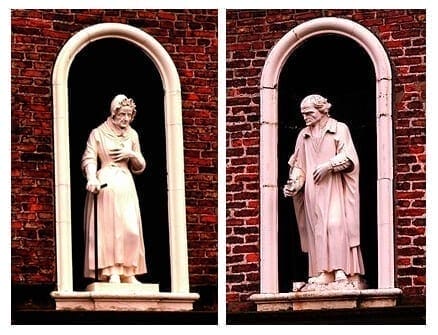

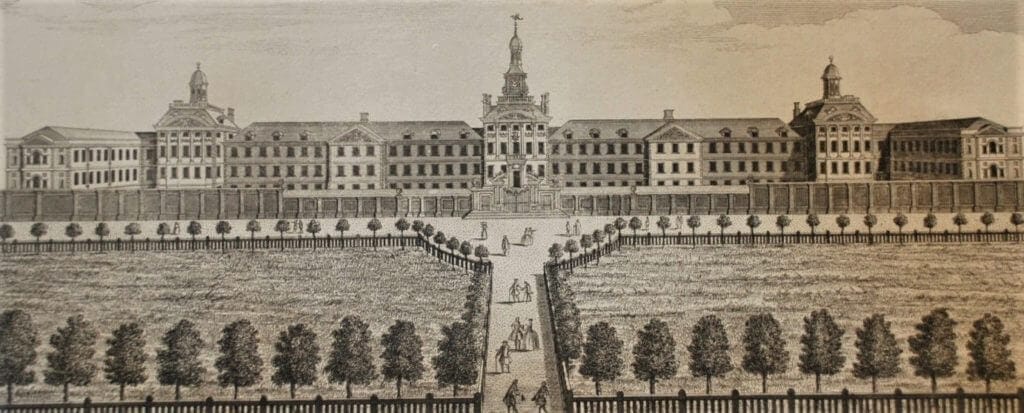

Kirkleatham Hospital (Fig 1) was founded by Turner near his home, Kirkleatham Hall, in 1676. It admitted men, women and children, who are depicted in eighteenth-century statues. The stunning old couple, in painted lead, must be real sculpted portraits. (Fig 2) The resident surgeon lived near the chapel. Each pensioner’s small cottage had its own garden, adding to activities and the social circle.

Turner’s first hospital had Dutch gables on either side of a simpler chapel. The gables suggest that the later Keelman’s Hospital of 1699 in Newcastle upon Tyne may have been influenced by Turner’s Kirkleatham. The wings had attic windows, which would have been prone to leak; today’s Kirkleatham Hospital was rebuilt in 1742, resembling Turner’s Bethlem. (Fig 3)

With Kirkleatham Hospital’s magnificent gates, stumpy folly turrets (Fig 4) stemming from pretty, curved loggias, and open pavilions, Pevsner4 questioned whether these were eighteenth-century. These elements must be, though, as none are on the print of the original Kirkleatham Hall. The whole design is unique, a special place for the residents to feel that they deserved a home in a palatial location. The grand facades and grounds were restful, beautiful, and meant to raise esteem. This was magnificent thinking.

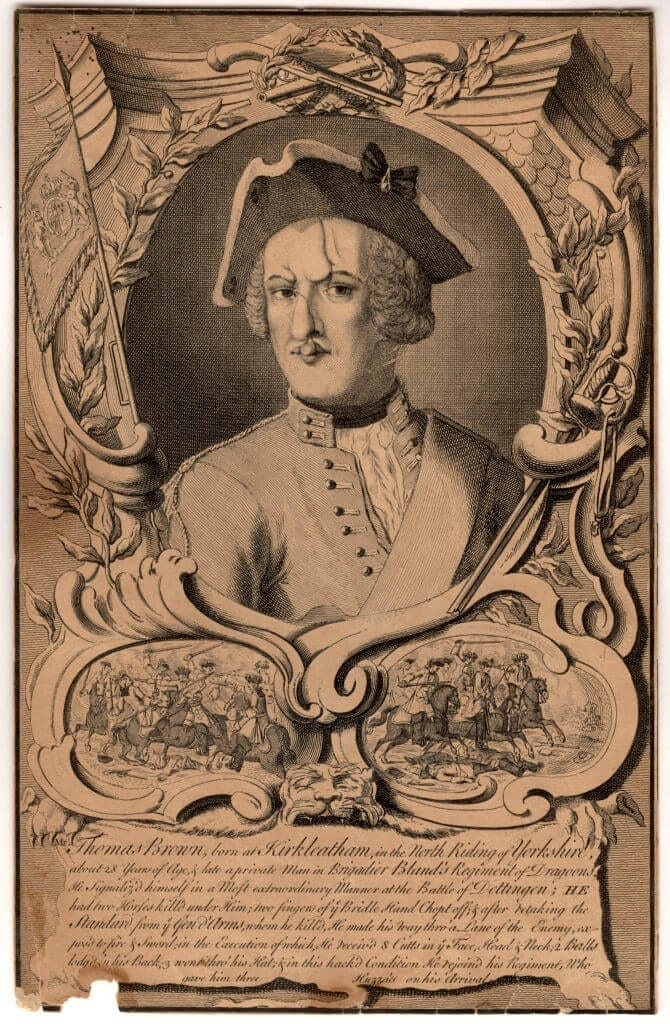

In 1743, a native of Kirkleatham, Thomas Brown, had his nose chopped off rescuing the flag in front of King George II at the Battle of Dettingen. The original 1700’s elm tree planted right outside the hospital in his memory was growing until recently, but had to be replaced due to Dutch Elm Disease. The King gave Brown a pension and a prosthetic silver nose, (Fig 5) but Brown drank himself to death within three years, lacking structure or care for post-traumatic stress.

William Turner’s nephew, Cholmley Turner, inherited Kirkleatham. At his uncle’s bequest, he founded Kirkleatham’s surviving, grand school in 1709, which is now a museum. The school was probably attended by a Tahitian man named Omai to improve his English before interpreting for James Cook on his final voyage. A farmer’s son, Cook had studied in nearby Great Ayton school. Cook had met Omai in 1772, the year after George III granted the New York Hospital Charter. Omai had outings with the schoolboys when he stayed at Kirkleatham Hall with Cook and Sir Joseph Banks. Earlier, on meeting George III, Omai had greeted His Majesty with a classic Yorkshire ‘How do!’, doubtless learned from Cook. Religious and ethnic integration were evident at Kirkleatham. Sir William Turner’s remained the Grammar School, then Sixth Form College in Redcar, until a very recent merger. Three centuries on, William Turner’s exam results outshone most British private schools, but without the fees.

The Kikleatham Hospital chapel of 1741 by the great Scottish architect James Gibbs is exquisite. The plan is based on Christopher Wren. The Venetian window, (Figb6) probably by William Price, resembles a winged altarpiece in stained glass. It shows the Adoration of the Magi, with William (right) and his elder brother John Turner (left) in the side panels. Joseph, behind Mary, looks Indian. With the turban, the black King with the incense personifies both Asia and Africa. This typifies the Enlightenment view of the continents as emblems of discovery, knowledge, trade, and the exotic. He stands in striking central prominence, with his gaze to the Virgin, which is also remarkable in its Enlightenment tolerance.

Opposite the hospital, against the village church, is Gibbs’ 1740 mausoleum, (Fig 7) built as a memorial to Cholmley Turner’s son, Marwood, who died on his grand tour, probably of typhoid. It is an imposing piece that gives an extraordinary parkland setting to the public area around the hospital. It also symbolises mortality – the speckled stone bands are called vermiculated rustication, meaning “rough, eaten by worms.” They are interspersed by smooth bands of stone representing life’s prime. That alternation is a metaphor for life quality in the midst of frailty; precisely what was going on in the hospital across the road. The mausoleum and hospital chapel tower echo Gibbs’ Radcliffe Camera in Oxford and St Martin in the Fields on Trafalgar Square, making Kirkleatham a miniature architectural paradise.

Development in recent years has neglected the aesthetic environment. Parking spaces in over-developed plots reign supreme, much more than loggias in beautiful, tranquil gardens. Aesthetics, philanthropy, and faith have been replaced by cheap buildings, unworkable budgets, and bureaucracy, failing to keep up with holistic needs for the elderly. The lessons of Kirkleatham’s past for the present day are: offer food, warmth, and shelter in a setting of beauty, peace, and safety, with a sense of community. Plan ahead, build to last.

Turner’s coat of arms features crosses called millrinds, which turned millstones. Hence, they were called ‘Turners’. Turner himself rotated the wheels of real progress. Kirkleatham Hospital is still performing its original function to this day. It is full of contented, elderly residents, and has been ever since it was founded. That breath-taking durability must be a good way of doing it.

References

- Dan O’Sullivan. ‘Some rarityes that lye in this lordship of yours called Guisborough’: the Cottonian manuscript transcribed. Yorkshire Archaeological Journal. Vol 84, 2012, pp 140-159.

- historyofparliamentonline.org

- John Gough Nichols. The Topographer and Genealogist. Nichols and Son, Westminster, 1846. pp 505-509.

- Nikolaus Pevsner. The Buildings of England. Yorkshire The North Riding. Yale University Press, New Haven. 1981.

STEPHEN MARTIN, MBBS, MRCPsych, LTCL (flute), retired neuropsychiatrist, is Visiting Professor, College of Music, Faculty of Arts, University of Mahasarakham and Honorary Professor of Psychiatry, University of Chiang Mai.