James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Adalbert Seligmann

Presented in an expanded version to the Chicago Literary Club, January 25, 1982

In the days when medical wards were full of patients consuming milk and cream along with graded Sippy diets supplemented by Sippy powders (later tasteless aluminum gels and suspensions) and surgeons were busily removing gastric cancers and ulcers, most medical students would have been expected to know the difference between a Billroth I and Billroth II operation. But considering the relatively low emphasis on medical history in medical schools, few students on being asked would have known the answer to “who was Dr. Billroth and when did he live?” It is unusual today for a patient to undergo surgery for peptic ulcer disease and that is certainly good. This being the case, perhaps we should cast an indulgent eye on what our students do not know and give them credit for what they are expected to master in our world of molecular biology.

Yet, since the Billroth I and II procedures are still with us today in the resection of gastric tumors and as they were the first successful gastric operations, a little medical history might be of interest. Theodor Billroth was one of the greatest surgeons, the legendary chief of surgery at the famed Algemeines Krankenhaus in Vienna. Born on Bergen on the island Rugen in the North Sea on April 26, 1829, he was the first child of Carl Theodor Billroth and Johanna Christina Nagle. The family could trace its origins to Pomerania, formerly a part of Sweden. The family name may have been spelled “Willrot,” “Willrath,” or “Willgeroot,” a derivative of the Gothic Weljan meaning “to strive” or to “struggle.”1

The Billroths were a middle class family that had genetically and culturally evolved a noble set of family traits. An uncle, Wilhelm Friedrick Billroth, was not present at the baptism, presumably busy practicing medicine in Stettin. Even earlier, a grand uncle, Johann Gottfried, had served as physician to the Swedish Court.

Billroth’s mother was a native of Berlin. Her father had married Dorothea Willich, Billroth’s maternal grandmother, a singer and member of the national theater in Berlin from 1803 to 1806.

When Billroth was five years old his father died of dysentery. His mother, then twenty-six years old, faced with raising of five fatherless children, moved her family to Greifswald, where her father-in-law, a man in his seventies, was the mayor. His education in Greifswald was that of the classical gymnasium, placing emphasis on Latin, Greek, geography, and literature. A striking document was his application at age nineteen years to take the final school examination.1 He writes: “In the past years I have become quite independent since my mother unfortunately was bedridden … My earlier inclination toward the study of medicine has become so strongly reinforced that I am firmly decided to pursue it.”

In this autobiographical sketch he also mentions his growing interest in classical Greek and Latin, as well as a facility in art, which he put to use in later years to amplify histological studies and medical lectures. It is surprising to learn that Billroth was not a promising student and during his time in the gymnasium required tutoring. One of his teachers described him as an “ingenium tardum”—a late bloomer, clumsy in expressing himself and an inept scholar early in life.

His mother, bedridden and suffering from tuberculosis, was basically a pragmatic woman who steered her son away from a career in the arts. A career in medicine was also encouraged by his uncle, Phillip Seifert, Professor of Pharmacology in Greifswald, and by a close family friend, Willhelm Baum, Professor of Surgery.

Billroth entered the University of Greifswald Medical School in 1848 and in 1849 transferred to the University of Gottingen Medical School. Two professors who most strongly influenced him at this time were Rudolf Wagner and Willhelm Baum. Wagner taught Billroth how to use the microscope, the ground work for future studies in pathology. Baum became a father figure whose multifaceted personality, basic knowledge, and extensive library helped Billroth develop the self-discipline and perseverance that characterized these formative years.

Billroth matriculated at the University of Berlin in the fall of 1851. At this time he was almost forced to give up his studies because of a financial crisis arising at the time of his mother’s death and the small inheritance that remained. Only with financial help from his grandmother was he able to finish his studies. He defended his doctoral thesis on September 30, 1852, on the role of the vagus nerves in pulmonary infections, and received his doctoral degree from the University of Berlin. He then broadened his knowledge by attending courses and clinics in Vienna and Paris, returning to Berlin in 1853.

He tried unsuccessfully to establish a private practice and spent two months without seeing a single patient. Urged by a friend Dr. C. Fock to apply as a surgical assistant to Bernard Van Langenbeck, it was his good fortune to be accepted. His first investigative work was on the pathological histology of tumors. In 1856 he qualified as an unsalaried lecturer and two years later he married Christel Michaelis, the daughter of a deceased physician and a woman known for her fine literary and musical taste.The couple had to initially support themselves from her inheritance.

In 1859, after several unsuccessful bids for a permanent position, he was offered an appointment as Professor in Surgery in Zurich. The position was secured with the help of Van Langenbeck, and there is an account of how his wife was able to lift his sagging spirits that year by fixing the letter offering him the position in Zurich to the Christmas tree.

During the next seven and a half years in Zurich (a time he looked back upon as being almost idyllic) he published over forty papers and his “Lectures on Pathology and Therapeutics, A Text of Fifty Lectures” achieved the status of a classic, was translated into ten languages, and subsequently went through sixteen editions.

In 1867 the faculty in Vienna was engaged in choosing a successor to Franz Schuh, the Professor in Surgery. Billroth was an obvious candidate and was unanimously selected. He accepted this position, which was confirmed by decree of the Emperor Franz Joseph. He rounded off his career in Zurich by tabulating his surgical experience, this at a time when few practitioners had the courage to record their failures.

Billroth at the age of thirty-nine years was the youngest member of the distinguished faculty that included names such as Rokitansky and Skoda. The Vienna Medical School was organized into two medical and surgical chairs, giving clinicians of opposing philosophies the opportunity to confront each other in a competitive struggle.

Johann Dumreicher was head of the first surgical service, aristocratic, opposed to investigative procedures, and interested in orthopedics; he left open a vast field of surgical disease for Billroth to pursue. Commenting on the two men in his autobiography the Philadelphia surgeon Samuel Gross states, “Dumreicher as his name implies is a dull drowsy sort of man, an old foggy without energy or life, and without the flair of interesting pupils. Billroth by comparison was full of soul, always busy, instructive, and full of resources under the most trying difficulties, a great pathologist, a good talker and a great operator.”2 There is little doubt that Billroth created jealousies when he demanded more beds and space for his surgical service. He referred to himself as the “North German Herring” and recognized that he would always be viewed as a foreigner in the insular Viennese medical community of his day.

The Franco-Prussian War in 1870 represented an interruption to his career in Vienna, but he made notable contributions to the care of the wounded and produced a monograph on the care and transportation of the wounded during war. Billroth had always felt his surgical career required that he experience military surgery. This curiosity plus a strong sense of German nationalism caused him to rush to the anticipated battlefields with his surgical assistant Vincenz Czerney without waiting for his request to be designated as an unpaid foreign medical delegate in the German theater of war. He was soon working fourteen to eighteen hours per day, managing a 400-bed hospital and performing or supervising numerous operations. One is impressed by his ability to throw himself voluntarily into this situation, assume a role of leadership, and make such a positive contribution. He was remarkable during these events for courage, capacity for self-sacrificing labor, and lack of regard for his personal safety or comfort. In the end he wrote, “I would have stayed the duration of the whole war. I would not have cared if I lost my position. A wife and children make one slave to circumstances.”3

His subsequent years in Vienna from a surgical standpoint assume a legendary character. The first laryngectomy for cancer was performed in 1873, a resection of cervical esophagus in 1877. Ultimately his most famous achievement, a partial gastrectomy in 1881 for cancer of the stomach. There are two aspects that make these accomplishments outstanding. There is the technical side of the operation, achieved in an era with limited anesthesia (only chloroform and ether), the absence of intravenous support, the inability to administer blood transfusions, and the lack of antibiotics to combat infection. What is more impressive is that these surgical adventures were not attempted without a firm basis of experimental animal work demonstrating their feasibility (albeit sometimes only a single dog would suffice). It is this latter characteristic of his work which justifies his designation as an academic surgeon.

In 1876 Billroth achieved a milestone in medical education with his monograph, “Teaching and Learning the Medical Sciences in German Universities.”4 This monograph is remarkable for the scope of its subject matter. His monograph reviews the history of medical education, the nature of a classical premedical education, the organization of a medical faculty, the nature of the examinations, and matters of financial support for medical education. In all, three hundred carefully written pages were produced by a man engaged in the day to day practice of surgery, teaching, and research. In 1908 Abraham Flexner began his influential study of medical education in America under the direction of Henry S. Pritchett of the Carnegie Foundation. Reading everything he could lay his hands on that dealt with the history of medical education in Europe and America, he found that the most important and stimulating volume was Billroth’s “Lehren und Lernen” (Teaching and Learning the Medical Sciences in German Universities).5 In 1924 Flexner was instrumental in promoting the first English translation of this work financed by the general education board.

The Austrian Crown Prince Rudolph, son of the Emperor Franz Joseph, was a friend of Billroth and supported the pioneering ideas of a private hospital with a non-sectarian school for student nurses. This resulted in the Rudolfinerhaus, in part supported by Billroth, who freely donated his surgical services to this hospital. In this context he also wrote an innovative and comprehensive book titled “The Care of the Sick at Home and in the Hospital: A Handbook for Families and Nurses.” Of major importance are the accomplishments of his many pupils, several of whom became professors of surgery and heads of surgical clinics throughout Europe. Karel B. Absolon has reviewed the accomplishments of these surgeons and traced their surgical lineage into this century.6

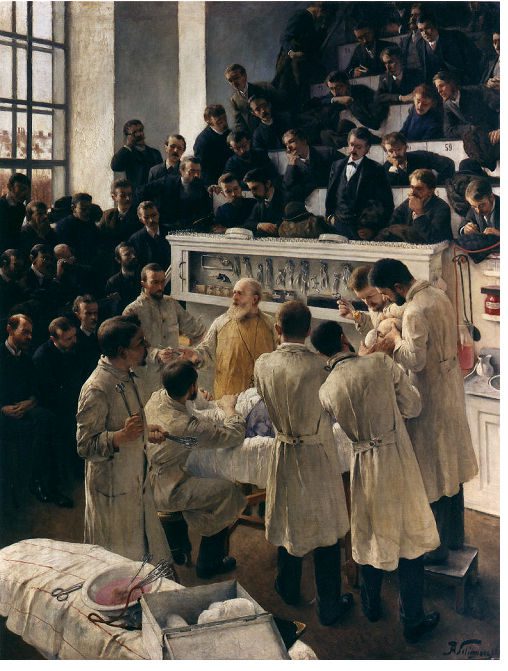

Prominent American surgeons who visited Vienna have left us their impressions of Billroth’s surgical clinic. George Washington Crile (1864-1943), a founder and director of the Cleveland Clinic, visited Vienna in 1872. He observed, “in those days the professor of surgery was a personality and Billroth was the most impressive of them all—positively god-like in demeanor. He not only wore a long Prince Albert coat suitable to such a position but always performed his work with the utmost formality. Promptly at nine o’clock the wide doors of his clinic swung open and Billroth with his staff of twenty assistants made a grand entrance. Everything was organized, each case had been studied, Billroth knew every detail. There was no more chance of error than there was in the performance of great play. As a teacher he was no orator but he was a lucid and painstaking lecturer. His cases were discussed with meticulous care, he making colored chalk drawings to illustrate them.”7

Earlier in 1868 Samuel D. Gross (1805-1884) recorded similar impressions. Speaking of Billroth, “he was somewhat above the medium height, he was of an immense frame with a marked inclination to stoutness, a large head, and a good open frank and intelligent face with dark hair and eyes. As a lecturer his style is conversational rather than forcible; his voice and manner are agreeable; and he totally captures the attention of his class. I heard him deliver an admirable discourse on lymphatic tumors illustrated by microscopic drawings and wet preparations and with frequent references to the blackboard, he being a ready draughtsman.” Gross went on to describe his surgical abilities: “fearless and bold, almost to the verge of rashness.” He mentions an excision of a carcinoma of the rectum accompanied by a great loss of blood, upon asking him the following morning how the patient was, he replied with a significant shrug of the shoulder, ‘he is moribund’ and passed on. Billroth has lately twice excised the larynx, the patient in one of the cases surviving in comparative comfort with the aid of an artificial substitute. What he may do in the way of heroic surgery it would be difficult to foretell. Possibly his next feat may be extirpation of the liver or the stomach. Billroth knew how to enjoy life, is fond of society, a composer, a superior pianist and in a word a remarkable person such as is rarely found in any profession.”

With regard to Billroth’s musical abilities it is worth mentioning that he was both a good pianist and violist, and it was at his home that his friend, the composer Johannes Brahms, brought to light many of his chamber music compositions. The two men enjoyed a friendship only rarely marred by misunderstanding that spanned a twenty-five year period, and they left us a fascinating record of their correspondence.

Billroth often gives us a wonderful insight into his attitude toward patients and the practice of medicine. Will historians of future generations be deprived of such material through a decline in letters written by one man speaking his mind to another freely and for the purpose of communication of his private thoughts?

The following passage from a letter written by Billroth in 1880 touches on an all too familiar theme. “Last year I protested my taxes because the government valued my income too high and these affairs have now drawn to a close. This year I have to pay besides my taxes on the house, the income taxes for two years, nearly 7,000 gulden. That is not funny anymore. I can only get this amount together if I stay in Vienna somewhat longer this time and come back earlier to see all the patients I can. Forgive this most prosaic, painful cry of a father of a family and be glad you don’t have to worry about the future of wife and children.”

Billroth was very proud of his home on 20 Alserstrasse and he wrote, “Johann Peter Frank at one time owned my house but as things go I simply took it as a possibility.” Johann Peter Frank (1745-1821) was a physician and great lover of music. He came to Vienna in 1795 as director of the Allgemeines Krakenhaus and Professor of Clinical Medicine. In 1779 he had produced the first real text on public health and is regarded as the founder of that discipline.

There are wonderful insights into his attitudes toward his patients and the practice of medicine. Writing in June, 1877 “please do not write how you intend to spend your vacation. I would so much like to be with you once more and away from Vienna. Here my thoughts are always a heavy load. It’s a necessity to be for a time among healthy and jolly people, then I will be happy to return to my work and duties.” In a similar vein, “when one is surrounded by sick people all day long one rather feels that to be healthy is an exceptional circumstance.”

A letter in August, 1886 describes his medical activities, “I don’t know when I can get away. My old teacher and colleague Arlt, the most famous eye specialist of our time, the teacher of the great Grafe, is very sick with senile gangrene. I cannot leave him unless his end comes or the possibility of doing an amputation occurs with some expectation of saving his life. Otherwise, too, I have much to do, and with the great heat it is very tiring. But there are certain joys at the same time; for instance, your roll of music which lies next to me. Now I have to visit Arlt in Pötzleinsdorf; then I have the clinic in the Rudolfinerhaus, and then several hours to operate on private patients, then my office hours, and then arrange to see a patient from Baden.” The day that Billroth describes was not unusual and he would often after a full day at his profession work until one or two o’clock in the morning, writing letters and surgical articles.

In June, 1877 Billroth nearly died of pneumonia. From this time on he felt his days were numbered and a preoccupation with his mortality frequently appears in his letters. On his birthday in 1890 he writes, “a life symphony of sixty-one bars is something of a problem when one doesn’t see any end to it. After my severe sickness of two years ago it is only a coda of some length … but after all, one lays life from a score laid in front of one by fate, and does it with more or less skill.”

We also see the doctor as a patient, “the excess of honor and love at my jubilee was I admit wonderful, but it was at the same time a sort of funeral service. I prepared my body with digitalis and other poisons so that I could join the festivities looking like a well man.” Billroth in the last year of his life referred frequently to the use of morphine for pain and to gain sleep. “I am a crippled crane, I have such a dreadful pain in my left leg that I can scarcely move about, the pain was so strong at night that I took a good deal of morphine.” Friederich Wilhelm Serturner, a pharmacist identified morphine in its pure form in 1803. It was said that “unnumbered millions had found it a friend which in the hands of a proper doctor relieved pain and when needed produced euthanasia.” Billroth’s use of it in sleepless nights and for pain was evidently not uncommon.

Students of medical history will marvel at Billroth’s capacity for productivity in the care of patients, education and research, and at the same time his involvement in music and other humanistic pursuits. This liberalism does not change the place history will accord his surgical scientific achievements or an assessment of the influence of his school of surgery which extends well into this century.

References

- Absolon, Karel B., The Surgeon’s Surgeon Theodor Billroth 1829-1894 Volume I, Coronado Press, Lawrence, Kansas, 1979 p. 2 and 10.

- Gross, Samuel D., Autobiography, George Barrie, Publisher, Philadelphia 1887, p. 224-225.

- Absolon, Karel B., The Surgeon’s Surgeon Theodor Billroth 1829-1894 Volume II, Coronado Press, Lawrence , Kansas, 1980 p. 47-84.

- Billroth, Theodor, The Medical Sciences in the German Universities, The Macmillan Co., New York, 1924.

- Flexner, Abraham, I Remember, Simon and Schuster, New York, 1924, p.114.

- Absalon, Karel B., The Surgical School of Theodor Billroth, Surgery 50″697-715, 1961.

- Crile, George, George Crile, An Autobiography Edited by Grace Crile, J. B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia and New York, 1947′ p. 56-57.

- Johannes Brahms and Theodore Billroth: Letters from a Musical Friendship, Translated and Edited by Hans Barkan, Normal University Of Oaklahoma Press, 1957.

JAMES L. FRANKLIN, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Chicago Society for the History of Medicine and the Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 7, Issue 1 – Winter 2015

Leave a Reply