Amber Mills

Anthea Gellie

Michele Levinson

Malvern, Australia

We sit at a phase in human development when life expectancy is greater than ever before. In classical Rome life expectancy was a mere 28 years for an adult, in Medieval Britain it had risen slightly to 30 years, and by the early 20th century 31 years. These figures were predominantly due to high infant mortality, and thanks to recent advances in science and medical technology, we have seen the greatest increases in life expectancy in the past century. Life expectancy in most developed countries is now more than 80 years.1 The leading causes of death before 1800 were infection, childbirth and trauma, war, or famine. In 2010 in Australia chronic diseases and frailty have taken their place, along with conditions such as Ischemic heart disease (IHD), stroke, dementia, or lung cancer.2

Death was once seen as a ritually created second birth in traditional societies, related to any type of post-existence such as rebirth or reincarnation.3 The core of these beliefs is that death was an event to be celebrated accepted, or even welcomed, an odd view from a modern perspective.

Historical views of death

In ancient Greece and Rome death in battle was perceived to be a privileged end by many, and the primary sources of the period reflect these norms. The Roman aristocratic funeral was a public event.

“When he has finished the eulogy of him, he begins praising the others who are present . . . recounting the successes and achievements of each. In consequence of this, since the reputation for virtue of good men is perpetually renewed, the renown of those who have achieved some noble deed is undying” (Polybius)

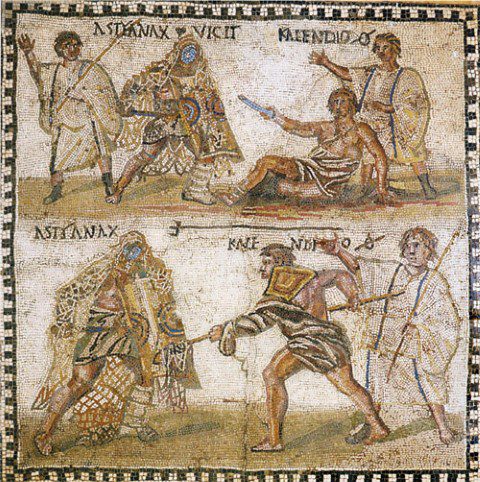

Suicide was an honorable alternative to defeat in battle, an anathema in modern times. The gladiator sports of ancient Rome, where death featured as a spectacle to be enjoyed, are famous. Suicide could also be seen as an act of defiance against the state. For women in this time death and sexuality were highly complex, and suicide could be used to compensate for sexual dereliction.4

Attitudes to life and death in our times contrast strongly with those of pre-modern times. Death was more pervasive, more present, always lurking over one’s shoulder, as represented in art of the era. Church Father Ambrose of Milan, for example, propounded the notion of death as a good for the Christian, as it delivered him from life’s calamities and evils and led him to the ‘true life.’5 Further to this, in the medieval literature references can be found to holy men and women with longings of a spiritual origination for their own deaths, as they represented a sweet release from this earthly world into the next, more spiritual realm of the divine where they could join their beloved Saviour. A ritual which seems arcane to us now, but was once common was the treating of death as a communal and public event, where family, neighbors and friends would gather around the bed of the dying person to pay their respects and to witness the event.6

At the end of the fifteenth century, the iconography of death took a surprising turn into erotic themes. Where previously in art, Death had scarcely touched the living to warn or designate, in the iconography of the sixteenth century, Ariès asserts Death is raping the living.7 He notes “countless” scenes or motifs in art and literature from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries featuring “death with love, Thanatos with Eros.” Examples of this include Bernini’s St. Theresa of Avila with God, which juxtaposes the agony of death with orgasmic trance, and the writing of the Marquis de Sade. These are erotico-macabre themes and reveal what he terms “extreme complaisance” for the spectacles of death, suffering and torture.7 This phenomenon marked a change in our psychological perception of death. Death was now being conceived of as some kind of transgression, a “break” from the ordinary events of life rather than a part of it.7 These erotico-macabre notions passed from iconography into the world of real events, losing their erotic characteristics, but becoming the well-known notion of romantic death we are familiar with from the work of the Brontes, Mark Twain, and Lamartine in France.7

“A lovely flower soon snatched away, To bloom in realms divine, Thousands will wish at Judgement Day, Their lives were short as mine” (Wesley).

Sociologists argue that our society has been profoundly influenced by science and new technological developments.8 Developments in the nineteenth century must be cited as contributing powerfully to the modern refusal to accept death, including the socio-economic revolution of the nineteenth century, industrialization, and urbanization.7 The hospital was no longer a shelter for the poor and pilgrims, but a place where “people were healed, where one struggled against death.”7 Ariès outlines a major change happening for death in the nineteenth century. Whereas previously death had been an expected, commonplace event, now a “new culture of grief shook the living.” Displays of emotion were hysterical.7 In the Victorian era very elaborate displays of mourning were the norm, such as elaborate mausoleums and attire. Widows would wear black attire for a year to two years, and then grey or lavender after that, and no lavish fabrics such as satin or velvets were worn. Mourning jewelry was fashioned out of a locket of hair or photograph of your loved one, and grievers who had lost their child or partner would wear them around the neck. Memorial photographs were taken of the deceased if the family could not afford a portrait.

Dramatic social, medical and economic changes in the twentieth century continued to contribute to changing views of death. The rise of medical technology in the early 1960s transformed the way we conceive of death. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) became an available and sought-after procedure in hospitals in developed countries around the world, and for the first time people whose heartbeat or respiration had stopped could be “brought back to life.” Coupled with earlier developments such as antibiotics and penicillin becoming commercially available in the 1930s and 1940s, and surgery evolving into a modern science, our medical future looked bright. Conversely, people who may previously have died naturally due to cessation of their heart or breathing now lingered on. Artificial respiration meant that once revived, people could potentially be kept alive, but at what cost? This brought with it many moral and ethical dilemmas surrounding decisions to resuscitate or not resuscitate considering the risks of significant brain damage or medical futility.

Positive outcomes for human mortality followed these changes, such as a decrease in infant mortality and a rise in life expectancy. Death as a natural consequence of life became much less visible. One of the outcomes of the advent of television in this era was that rather than viewing the typical, slow death experienced by many older people, dramatic deaths were broadcast alongside dramatic rescues from the clutches of death, leading to the public beginning to accept these dramatizations as normal and realistic possibilities.9 There are several themes which recur again and again in the Hollywood representations of death. It is always a romantic event, a violent event—or we also witness time and time again death-defying CPR—creating the impression that successful resuscitation is a common occurrence, even in the elderly population. In contrast, the slow, disintegrating dying of the frail is invisible to most of the community. The prevalence of nuclear families and the participation of women in the workforce have meant there are no longer large, extended families to care for sick and dying relatives.

Today—A culture of hope

The revolution in medical technology has given us the illusion of control over death. Added to this we have developed a “culture of hope” in a medical setting, particularly in relation to our “war on cancer” and other chronic illnesses. Implicit in the ‘war’ is a message of hope—if one has enough hope, it will change the course of the disease. Discussion of death robs a person of hope. The culture of hope infers that it is never the right time to discuss end of life preferences as it will induce a loss of hope in the patient. However, perceptions are different to reality. In one study 80% of participants said that they definitely or probably would like to talk with a doctor about end-of-life wishes, but only 7% actually had a doctor speak with them about it.9

Surveys have determined that for most people, their idea of a “good death” would be at home or in a hospice environment, rather than in a hospital which is where the majority of deaths currently occur.10-12 A good death probably does not involve, for anyone, having CPR performed in a hospital bed while the family wait outside, curtains drawn.13

Conclusion

A historical view of death encompasses a review of social practices that we would be tempted to term “extreme”—the elaborate mourning rituals of the Victorian period; the erotic portrayal of death in medieval art. We might consider these practices as extreme but what they did accomplish was an acceptance of death, even a celebration of death. In contemporary times we no longer benefit from this. We rail against death as an enemy, employing the culture of hope and an arsenal of medical technologies to defeat the foe. When we cannot arrest the inevitable march of death, we lament the patient’s brave struggle, having lost the battle against terminal illness. Our exposure to artificial representations of death only cements this warped view—what we see on television and in film are largely unrealistic portrayals of death. When we do face death we are often ill equipped to deal with its reality.

References

- The World Factbook [electronic resource]. (Accessed from http://nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn4591476).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of death, Australia [electronic resource] / Australian Bureau of Statistics. In: Statistics ABo, editor. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Eliade M. Mythologies of Death: An Introduction. In: Reynolds FE, Waugh, Earle H., editor. Religious Encounters with Death: Insights from the History and Anthropology of Religions. University Park and London: The Pennsylvania State University Press; 1975. p. 13-23.

- Edwards C. Death in Ancient Rome. New Haven and London: Yale University Press; 2007.

- Schumacher BN. Death and Mortality in Contemporary Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

- Hick J. Death and Eternal Life. Great Britain: Macmillan; 1985.

- Ariès P. Western attitudes toward death: From the Middle Ages to the Present. Baltimore & London: The John Hopkins University Press; 1974.

- Zimmermann C, Rodin G. The denial of death thesis: sociological critique and implications for palliative care. Palliative Medicine. 2004 Mar;18(2):121-8.

- Krisman-Scott M. The room at the end of the hall: Care of the dying, 1945–1976. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania; 2001.

- Callahan D. US health care: the unwinnable war against death. Health Economics, Policy and Law. 2012;7(04):455-66.

- Ellershaw J, Dewar S, Murphy D. Achieving a good death for all. BMJ. 2010;341:c4861.

- Grande G. Palliative care in hospice and hospital: time to put the spotlight on neglected areas of research. Palliative Medicine. 2009;2009(23):187-9.

- Bowling A, Iliffe S, Kessel A, Higginson IJ. Fear of dying in an ethnically diverse society: cross-sectional studies of people aged 65+ in Britain. Postgrad Medical Journal. 2010;2010(86):197-202.

- Mackay MJ. A time to die. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2004 Dec 6-20;181(11-12):667-8.

, PhD, completed her doctorate in developmental psychology. She is a research fellow in the Cabrini-Monash University department of medicine.

is completing a master’s degree in religious studies and editing and publishing. She is a research assistant in the Cabrini-Monash University department of medicine.

, MD, FRACP, FCICM, Grad Cert Clinical Research is an associate professor of medicine at Cabrini-Monash University, as well as a clinical dean at Cabrini-Monash Clinical School. She has over 15 years of experience in general medicine. The work of the Cabrini-Monash Department of Medicine focuses on end of life decision making, especially barriers to discussion.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 6, Issue 3 – Summer 2014

Leave a Reply