Adam R. Shapiro

Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States

Public Domain, via Wikimedia Common

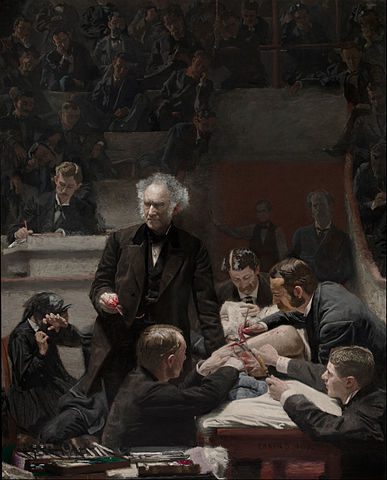

Thomas Eakins’s 1875 painting The Gross Clinic has long been considered one of the great works of nineteenth-century American art. Yet its depiction of a surgical demonstration by Dr. Samuel D. Gross and his colleagues at Jefferson Medical College was controversial from the moment of its completion. It was rejected for exhibition in the art galleries of the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia (though it was displayed in the army medical tent). When displayed in New York a few years later, it met with reviews that praised its execution but derided its subject matter. Some scholars attributed its initial reception to ambivalence about its gory realism, its flecks of blood on the leg of the surgical patient and on the wrists and hands of the surgeons. The crowded and violent nature of the composition was seen as technically masterful and undoubtedly accurate, but too upsetting to the Victorian sentiments of the American public. The Gross Clinic was too clinical, too precise to count as art.1

Others have suggested that the popular reactions to Eakins’s work might be best understood in light of the sexual politics of the artist and his circle. A few years after this painting was first displayed, public scandals emerged about Eakins’s use of nude models and allegations about his sexual conduct. There is some indication that rumors about such behavior date back to the era of the Gross Clinic. As a result, Eakins’s personal life has contributed to arguments for sexually symbolic readings of the painting, ranging from psychoanalytic interpretations of scalpel-wielding as part of a homoerotic castration narrative, to representation of the anatomist—and Eakins by proxy as the artist—as embodiments of dominating masculinity.2

Art critics in the late nineteenth century emphasized emotional affect as a measure of a painting’s ability to spiritually uplift, inspire, or transform. Even Eakins’s most obvious religious painting, his 1880 Crucifixion, was criticized as being too fixated on anatomical precision, more concerned with the way the blood oozed than the ways it redeemed sin. The figure on the cross, face obscured by shadow, evoked nothing that moved the spirit.

One thing that no one has suggested about The Gross Clinic is that it was a religious work, in part because the painting speaks to a religious theme that is inaudible to those who anticipate more traditional Biblical themes. In order to perceive the religious nuances of The Gross Clinic, one must focus on its eponymous subject. Dr. Samuel Gross was not just an eminent surgeon; he was—as the painting depicts—a teacher of surgeons. No matter how faithfully Eakins represented the clinic, his painting does not, in any literal sense, capture the words that Gross was uttering. But with Gross’s words at hand, we can see how their truths are captured on the canvas.

Gross wrote much about surgical practice during his career, and little of that writing goes beyond technical accounts of procedures and their results. But in his posthumously published autobiography, Gross reveals more about how he understood the human body as part of a divine creation:

I believe God to be just and merciful, without any of the attributes that disfigure and disgrace our feeble, finite natures, and that whatever happens takes place through the agency of laws inherent in matter from all eternity. All diseases, epidemics, and accidents are the result of a violation of these laws, and of our own ignorance, crimes, or misdemeanors.3

This is not the kind of religious view that cites the Bible for proof. It does not speak of Jesus or salvation, yet there is a strong moral vision that puts these words in the mind of a surgeon. God has created a world that is perfect, or as perfect as the agency of natural laws permits. The human body is a creation of a just and merciful God. At the end of a century in which theologians looked to the intricacy of design in the human body to justify claims about the wisdom, power and goodness of God, Gross has taken that perspective to its end. His cosmology explains the origins of illness, disability, disfiguration, and bodily ills. They are a consequence of human corruption. As a surgeon who lived through the Civil War and wrote a manual for military surgery, he had no shortage of experiences with the kind of damages to the body human ignorance or malice could create.

In such a world, the surgeon is one who restores (or at least tries to) a divine perfection to the world. And the artist is one who does God’s work best when he allows the full detail of God’s creation to be shown without euphemism. Centuries of medical illustration have struggled with the idea that individuals are not ideal specimens. No one person exhibits the perfect example of human anatomy. Each person is individual, unique, abnormal, in his or her own way. This has been a profound philosophical issue lurking in the background of medical and anatomical pedagogy. How much ought one teach idealized abstractions, and how much should students learn from the peculiar instances of a single specimen? Medical textbooks and surgical demonstrations have long attempted to balance between the universal and the particular. Eakins gives an answer to the pedagogical debate in his portrayal of Gross’s applied theology: the particular “feeble and finite nature” of the universal goodness of God and creation. But the ills that befall us—“diseases, epidemics, and accidents”—are the consequences of our own fallen state. In seeking to restore our bodies to grace, the surgeon is, in reality a saint.

The Gross Clinic is a hagiography of a saint of the modern scientific era. His symbol is the scalpel, and he is performing a miracle of healing. Eakins conveys this in language so subtle that it is taken for the simple literalism of fidelity to realism.

Resources

- Michael Fried, Realism, Writing Disfiguration: on Thomas Eakins and Stephen Crane (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987).

- Jennifer Doyle, “Sex, Scandal, and Thomas Eakins’s The Gross Clinic,” Representations, 68, (Autumn, 1999).

- Samuel W. Gross and A. Haller Gross, eds., Autobiography of Samuel D. Gross, M.D., Vol. 2. (Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1893

ADAM R. SHAPIRO, Ph.D. is a research associate in the Science, Religion, and Culture Program at Harvard Divinity School. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago and has taught at universities in the U.S.A., Canada and the U.K. He is the author of Trying Biology: The Scopes Trial, Textbooks, and the Antievolution Movement in American Schools.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 9, Issue 1 – Winter 2017

Leave a Reply