JMS Pearce

Hull, England

James Paget (1814–1899) is remembered for his original accounts of “osteitis deformans,” universally known as Paget’s disease of bone,1 and for his original description of Paget’s disease of the nipple, a sign of intraductal carcinoma.2 He made extensive contributions to pathology3 and to surgery.4 As a student at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, he was the first to discover the parasitic nematode Trichina spiralis in muscle during dissection; Richard Owen, his teacher, named it and published an account, barely mentioning Paget. He also described cases of pulmonary embolism, and the origins of the carpal tunnel syndrome may be found in Paget’s description in 1854 of median nerve compression resulting from a fractured radius.5

Paget’s disease of bone

On 14 November 1876, James Paget read his paper to the Royal Medico-Chirurgical Society On a form of chronic inflammation of the bones ‘osteitis deformans.’ He described a forty-six-year-old gentleman who began to be subject to aching pains in his thighs and legs. They were felt chiefly after active exercise but were never severe, yet the limbs became less agile or, as he called them, less serviceable. Three years later, the left tibia had become larger and had a well-marked anterior curve, as if lengthened while its ends were held in place by their attachments to the unchanged fibula. The left femur also was now distinctly enlarged, and felt tuberous.

Over the next seventeen years, “The skull became gradually larger, so that nearly every year, for many years, his hat, and the helmet that he wore as a member of a Yeomanry Corps needed to be enlarged. In 1844 he wore a shako measuring twenty two and a half inches inside; in 1876 his hat measured twenty-seven and a quarter inches inside.” Twenty years after the first consultation, the patient developed an osteoid cancerous growth around the left radius, which proved fatal.

At necropsy, the bones were enlarged, deformed, and so soft that a razor could cut them; there was periosteal new bone formation. Microscopic examination showed widened Haversian canals containing homogeneous or granular basis, containing cells of round or oval form about the size and having much the appearance of leucocytes. Larger nucleated cells (osteoclasts, named Paget’s cells) were also present, and fibers or fibro-cells, sometimes in considerable quantity. He suggested that it might be called after its most striking character, osteitis deformans.

In his five patients he observed several complications. They included painful deformities of the spine, pathological fractures, retinal hemorrhage, visual loss with blindness in four patients, and deafness; these resulted from hypertrophic bone encroaching on the foramina through which run the cranial nerves. In three of the original five cases, cancer appeared in later life.

In 1882 he reported observations of additional cases, of which he said:6

I hope that they may help to clearly indicate the chief characters of the disease to which I venture to give the name of osteitis deformans, and which, so far as I know, was first described in the paper published in the 60th volume of the Society’s ‘Transactions.’ Since that time, about 5 years ago, I have seen several cases of the disease, and have recorded concerning them the facts which follow.

The seven cases now related seem sufficient when added to the five recorded in the 60th volume, to justify the giving of a distinctive name and a definite general description of the disease observed in them. It usually affects many bones, most frequently the long bones of the lower extremities, the clavicles, and the vault of the skull. The affected bones become enlarged and heavy … curved and misshapen. The disease is very slowly progressive… But neither the pain nor the heat are constant, nor do they continue during the whole progress of the disease …. In all the cases traced to the end of life, death has ensued through some coincident, not evidently associated, disease…

In all the cases I have seen, the most characteristic appearances are the loss of height indicated but the low position of the hands when the arms are hanging down; the low stooping, with very round shoulders and the head far forwards, and with the chin raised as if to clear the upper edge of the sternum; the chest sunken towards the pelvis, the abdomen pendulous; the curved lower limbs, held apart and usually with one advanced in front of the other, and both with knees slightly bent; the ankles overhung by the legs, and the toes turned out. The enlarged cranium, square looking or bossed, may add distinctiveness to these characters, and they are completed in the slow and awkward gait of the patients, and in the shallow costal breathing, compensated by wide movements of the diaphragm and abdominal wall, and in deep breathing by the uplifted shoulders.

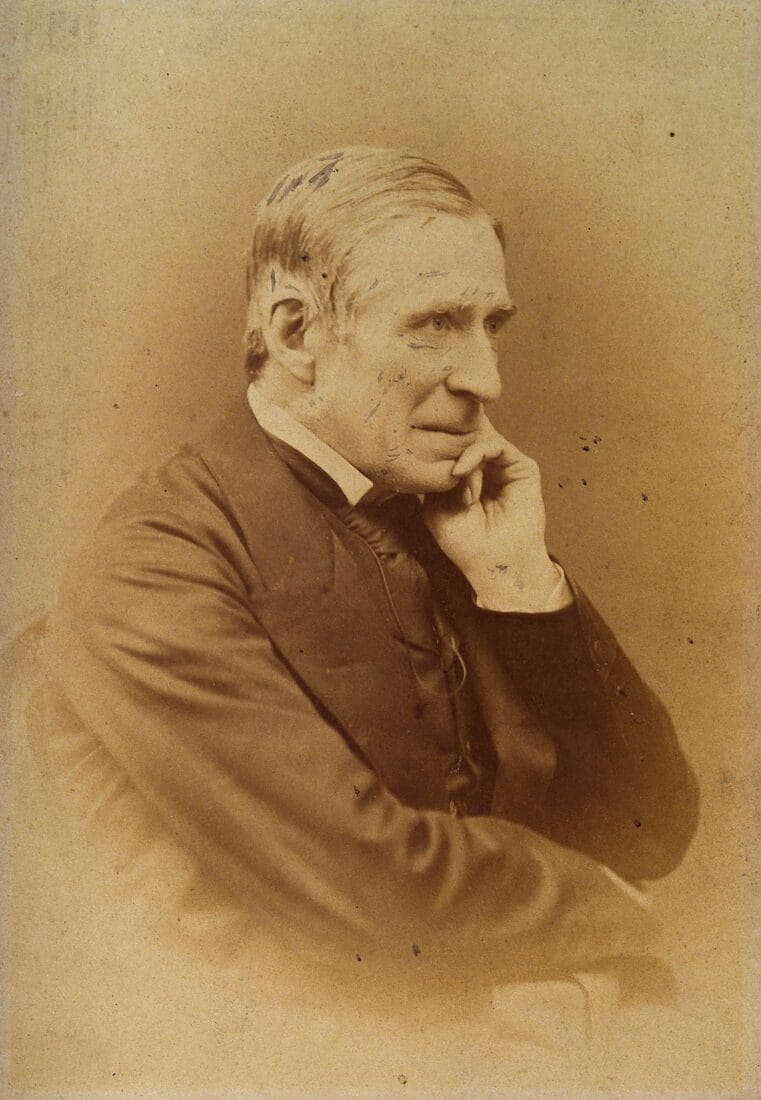

James Paget

James Paget was born in Yarmouth in 1814, the eighth of seventeen children. His father, Samuel Paget, was a prosperous local brewer; an older brother, Sir George Paget, became Regius professor of physic in Cambridge. James was a good artist and botanist, who in 1834 with his brother Charles published a book A Sketch of the Natural History of Yarmouth and Its Neighbourhood, which contained the names of more than 700 insects and 1000 plants.

At the age of sixteen he was apprenticed to Charles Costerton, a general practitioner in Yarmouth, before graduating MRCS in medicine from St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1836. He worked as a medical journalist, lecturer in physiology and students’ warden at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, and was curator of its museum. In 1841, he was appointed Surgeon to the Finsbury Dispensary. In 1843, he was one of the original three hundred surgeons elected FRCS. 1847 was a memorable year for him when appointed Professor of Anatomy and Surgery at the RCS (Arris and Gale Lecturer), and Assistant Surgeon at Barts. He was not appointed full surgeon until 1861.

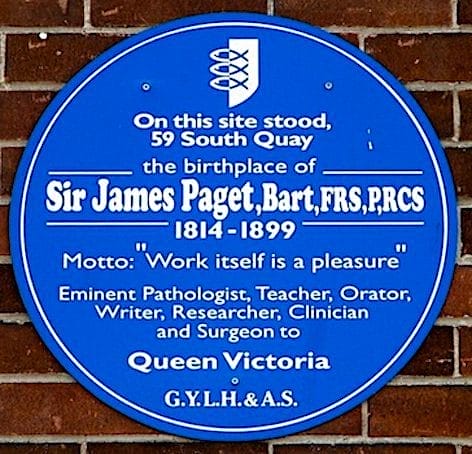

Paget was an outstanding diagnostician, surgeon, and pathologist.7 A man of exceptional industry, his coat of arms carried the family motto—Labor ipse voluptas—Work itself is pleasure. He possessed great humane and intellectual qualities,8 and was highly regarded for his shy and retiring manner, his clarity of expression and eloquence. The Prime Minister W.E. Gladstone thought so highly of his public speaking that he said he divided people into two classes—those who had and those who had not heard James Paget. His friends included: Cardinal Newman, Ruskin, Tennyson, Robert Browning, George Eliot, Tyndall, Hughlings Jackson, Thomas Huxley, Charles Darwin, and Pasteur.

His many lectures ranged widely over surgical topics, pathology, physiology, education, and theology in science. Some were collected in his 1853 book Lectures on Surgical Pathology, and in Clinical Lectures and Essays, 1875.

With G.W. Callender and Sir Thomas Smith he was one of the first to methodically analyze the education and subsequent careers and failures of over one thousand medical students, with consequent recommendations.9

He loved Italian music and the works of Bach. He also extolled the virtues of brevity of expression: “To be brief is to be wise, to be epigrammatic is to be clever.” He was a devout man, who held daily family prayers; the next two generations of his family produced no less than two bishops and an archbishop.10 He married Lydia née North in 1844. They had two daughters and four sons: the eldest, John, became a distinguished barrister and a QC; Francis was Bishop of Oxford 1900–1911; Henry Luke was Bishop of Stepney and Chester; and Stephen was a surgeon, essayist, and biographer. His successors included a remarkable number of titled bishops and military figures of distinction.

His eponymous disorders include Paget’s disease of bone—osteitis deformans; Paget’s disease of nipple—intraductal carcinoma; Paget’s extramammary disease—familial anogenital cancer; Paget-von Schrötter syndrome—axillary vein thrombosis; Paget’s abscess—a residual abscess; and Paget’s test—fluctuation on palpation of a mass to differentiate between solid and cystic lesions.

Amongst many honors and awards he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society aged thirty-seven, President of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1875, and Vice Chancellor of the University of London. He was appointed Surgeon Extraordinary to Queen Victoria in 1858 and was elected baronet in 1871. The James Paget University Hospital in Yarmouth was officially opened on 21 July 1982; there is a Paget Ward at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.

He completed writing his memoirs in 1886. His son Stephen, himself a surgeon, vivisectionist, and biographer, edited his memoirs and letters in 1901.11

A sample of James Paget’s diverse publications:

- A descriptive catalogue of the anatomical museum of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital. 2 vols. London: John Churchill, 1846.

- Lectures on nutrition, hypertrophy, and atrophy: delivered in the Theatre of the Royal College of Surgeons, May 1847 by James Paget; reported by William S. Kirkes, 1847.

- Lectures on the processes of repair and reproduction after injuries: delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 1849.

- On fatty degeneration of the small blood-vessels of the brain, and its relation to apoplexy: communicated to the Abernethian Society of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, 1850.

- Lectures on tumours, delivered in the theatre of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, 1851.

- Manual of physiology by William Senhouse Kirkes, assisted by James Paget, 1853.

- Lectures on surgical pathology, delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England; revised and edited by William Turner, 1865 et seq.

- What becomes of medical students, 1869.

- Clinical lectures and essays by Sir James Paget, edited by Howard Marsh, 1875

- On some of the sequels of typhoid fever.,1876.

- The Morton lecture on cancer and cancerous diseases: delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England on Friday, Nov. 11, 1887.

- Studies of old case-books, 1891.

- Selected Essays and Addresses by Sir James Paget, Longmans, Green & Co., 1902.

James Paget died, aged eighty-five, on 30 December 1899 at his home, 5 Park Square West, Regent’s Park. His funeral took place at Westminster Abbey; Lord Lister was a pallbearer. He was buried in Finchley Cemetery.

References

- Paget J. On a form of chronic inflammation of bones (osteitis deformans). Med-chir Trans 1877;60: 37-64. Reprinted in Med Classics, 1936, 1, 29-71.

- Paget J. On disease of the mammary areola preceding cancer of the mammary gland. St Barth Hosp Rep 1874; 10: 87-89.

- Turk JL. Sir James Paget and his contributions to pathology. J Exp Path 1995;76, 449-456.

- Dubhashi, S.P., Sindwani, R.D. Sir James Paget. Indian J Surg 2014;76: 254–255

- Pearce JMS James Paget’s median nerve compression (Putnam’s acroparaesthesia) Practical Neurology 2009;9:96-99.

- Paget J. Additional Cases of Osteitis Deformans. Med Chir Trans 1882;65:225-36.

- Pearce JMS. Sir James Paget: a biographical note. Quart J Med1997;90(3):235–237.

- Roberts S. Sir James Paget: the rise of clinical surgery, Eponymists in Medicine, London, Royal Society of Medicine Services, 1990.

- Paget J. What becomes of medical students. Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital Reports 1869; 5: 238–42.

- Paget S. Paget, Sir James. In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 1911;20 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 451–452.

- Paget S. Memoirs and Letters of Sir James Paget. London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1901.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.