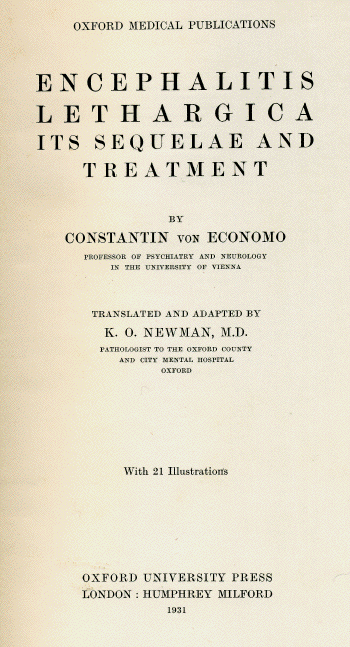

Encephalitis lethargica was a worldwide epidemic during the years 1918-1930 that resembled influenza. It was first described in Vienna in 1916 by Constantin von Economo in thirteen patients suffering from unusual neurological symptoms that he thought constituted a new entity and called encephalitis lethargica. Similar cases were described at the same time in a French military hospital for neuropsychiatric disorders. The disease may have first occurred in 1915 in Romania following the movement of troops during World War I. Further cases were reported from France in 1916-1917. By 1918, the number of cases reported in Europe had increased rapidly and the disease became epidemic at the same time as influenza. Occurring mostly during the winter months, it may have affected as many as one million persons, many of whom died or were left with permanent brain damage.

Early symptoms resembled influenza, often upper respiratory, mild, and nondescript. The patients often became very sleepy, with fever and some movement disorders, including a mask-like facial appearance. Reported mortality was about 30% but many mild cases most likely were not reported. The onset, though often gradual, could be quite sudden and some patients fell asleep and died within two weeks. Chronic sequelae sometimes followed immediately but typically occurred after one to five years, occasionally as late as forty-five years following the initial infection. A Parkinsonian syndrome dominated the clinical picture, but sleep disturbances, oculomotor abnormalities, involuntary movements, speech and respiratory abnormalities, and psychiatric disorders were also common features.

Ten- to thirty-year-olds were most commonly affected. Person-to-person spread was uncommon. Rarely the disease occurred in entire families or communities. The estimated incubation was up to four weeks. Postmortem brain examination of affected individuals revealed extensive inflammation and tissue destruction, especially in the basal ganglia and thus accounting for Parkinson’s like symptoms. Infection by bacteria or by viruses such as poliomyelitis or another enterovirus has been proposed as a cause, also autoimmunity. Despite occasional claims of the isolation of an H1N1 influenza virus, a relation to influenza has never been satisfactorily established. Interestingly, it has been speculated that Adolf Hitler may have had encephalitis lethargica as a young man, accounting for his Parkinsonism as an adult.

In a search for clues, investigators studied other twentieth-century viral epidemics such as Japanese B encephalitis. This disease occurred mainly in the summer, was transmitted by mosquitoes from birds and domestic animals, and also sometimes caused progressive neurological complications. Other viral diseases were summer encephalitis in St. Louis in 1933 and 1937, and myalgic encephalomyelitis in Britain. Historians and investigators have also pointed to other epidemics that resembled encephalitis lethargica, such as the English sweating disease of 1529 and further epidemics in Italy, Germany, and Sweden, as well as the rare putative sporadic case with similar clinical features. Research into the cause of the disease has been limited by the paucity of material that could be examined by modern techniques, and after one hundred years the cause of encephalitis lethargica remains unknown, nor may we comfortably posit that it or a similar illness will not strike again.

References

- Dourmashkin RR. What caused the 1918-30 epidemic of encephalitis lethargica? J R Soc Med 97;90:515.

- Mortimer PP. Was Encephalitis Lethargica a Post-Influenzal or Some Other Phenomenon? Time to Re-Examine the Problem. Epidemiology and Infection 2009;137: 449.

- Hoffman LA and Vilensky JA. Encephalitis lethargica: 100 years after the epidemic. Brain 2017: 140; 2246.

- Foley Paul Bernard Encephalitis Lethargica, Springer Verlag, 2018.