JMS Pearce

Hull, England

When Winston Churchill memorably referred to his bouts of depression as “black dog,” in two words he painted a picture that embraced feelings, which otherwise would have taken hundreds of words to describe. I have to confess a liking for certain medical metaphors. Though they can be overused in medical and biological writing, when employed with discernment they add color and at times crystallize complicated clinical phenomena. Many are rhetorical devices that appeal to our sensibilities; many are simply useful repetitions or extensions of expressions in everyday language, such as “he’s going downhill,” “she’s on the mend,” or “a burning pain.”

Probably originated by Aristotle in his Rhetoric and Poetics, metaphors (ancient Greek μεταϕορά, carry/transport) are the transmission of a linguistic expression into a different context than that in which it was expected. Many gradually become so embedded in language that we forget their origins and usage, which perhaps adds to their allure.

Some philosophers regard metaphors as a system of thought distinct from logic. Others hold that all speech is primarily metaphorical. Friedrich Nietzsche, for example, claimed “literal” truths are simply metaphors that have become worn out and drained of sensuous force. There is a vast literature in linguistics and psychology dealing with recondite concepts of metaphorical symbolism and application, which are beyond this paper. In medicine, metaphors usually are no more than useful, faintly amusing aids to visualize, describe, or memorize—graphically or figuratively—objects, signs, or ideas otherwise easily forgotten. In purpose, they resemble eponyms, metonyms, and similes.

Conventional metaphors abound in the general concepts of the opposing issues of health and disease, often couched in military terms. Trials include cohorts of patients; an infection is overwhelming, T-cells can be killer cells; a cancer is malignant, invasive and infiltrating, and the liver is riddled with it; we have an armamentarium of therapeutic weapons to fight or wipe out the disease.

Examples of medical metaphors

In mental illness metaphors are common. Psychotics were deemed lunatics; schizophrenics have a split mind. Depressives may feel embittered or down and have the blues; mood is volatile, often described as flat as a pancake. Mania bubbles over with wild ideas. Butterflies in the stomach, tension, and light-headedness accompany anxiety.

General medicine and surgery are especially rich in culinary metaphors; fruit and vegetables are often used. Animal and topographical metaphors are also common. They conjure up vivid, familiar everyday images to describe or symbolize many medical conditions.

Adam’s apple refers not to the book of Genesis but to the visible larynx.

Bats wing tremor: the irregular coarse movements of the outstretched arms that characterize Wilson’s disease, or hepatolenticular degeneration.

Berry aneurysm is a term applied to congenital aneurysms (localized swellings) of cerebral arteries prone to rupture, causing subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Bovine cough refers to the non-explosive cough signifying vagal or recurrent laryngeal nerve lesions typically caused by apical lung (Pancoast) tumors.

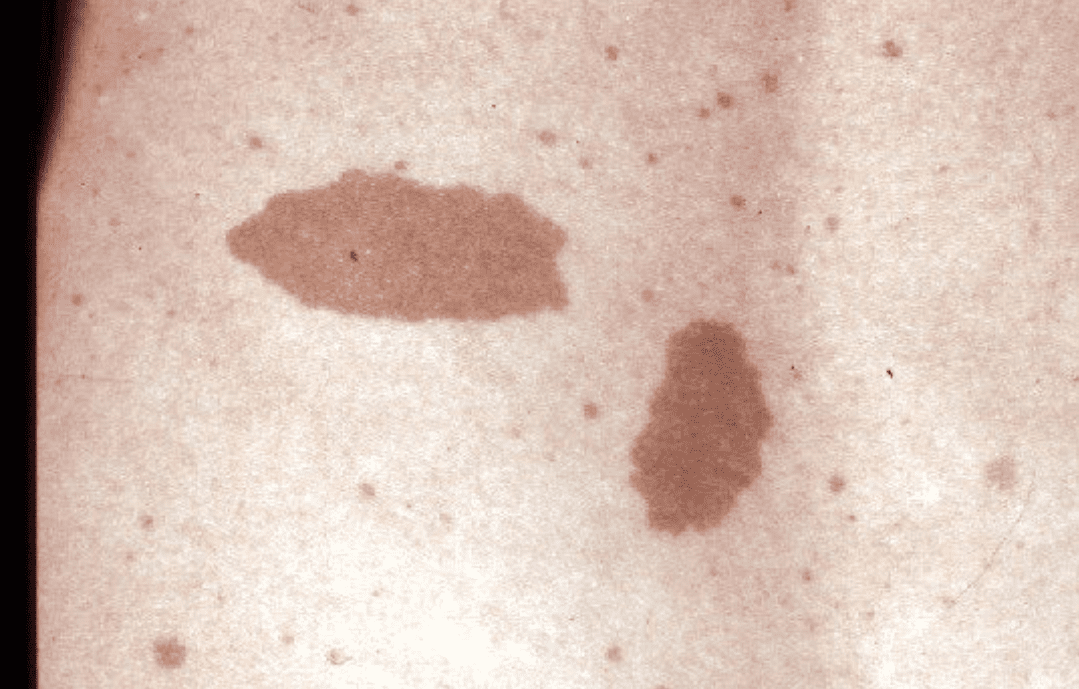

Café au lait patches characterize neurofibromatosis and coffee grounds the vomitus of an upper gastrointestinal bleed.

Cannonball describes multiple large, well-circumscribed, round metastases in the lungs.

Cauliflower ear reflects organized hematomata in rugby players and boxers.

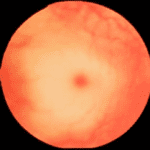

Cherry-red spot at the macula is seen in occlusion of the central retinal artery; a cherry-red spot is also seen in Tay-Sachs disease.

Chicken wings are sometimes used to describe the wasted shoulder muscles of facio-scapulo-humeral dystrophy.

Christmas disease refers not to the religious festival but to the name of the patient Stephen Christmas, afflicted with Hemophilia B, factor IX deficiency.

Cluster headache refers to the frequent daily sequence of attacks of headache of daily unilateral intense pain lasting 30 to 120 minutes accompanied by a running red eye, blocked nostril, and intense restlessness. The cluster of daily attacks cease after four to twelve weeks. Attacks often occur at precise times in the night, so it has been called alarm clock headache. Similar are the metaphors thunderclap headache, and exploding head syndrome.

Cogwheel rigidity is self-explanatory; it describes the intermittent increase in resistance to passive movement felt by the examiner in a Parkinsonian limb. The cog wheeling is a tremor superimposed on lead pipe rigidity—distinct from the clasp-knife sensation of pyramidal spasticity, a metaphor to suggest the opening and closing of a penknife.

Cramps: literally bend or twist, and are involuntary, violent, and painful contraction of the muscles. Many occupational cramps are described.

Dinner fork deformity is a classic clinical and radiologic sign in Colles fracture of the radius.

Doughnut cells: characterize anaplastic large-cell lymphoma.

Flapping tremor (asterixis): intermittent lapses of posture when the arms are extended consisting of asymmetrical, bilateral, flapping at the wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints. Metabolic encephalopathies caused by hepatic, respiratory, or renal failure are the common causes.

Glue ear: a middle ear effusion.

Grape-like: the vesicles of hydatiform mole.

Greenstick fracture: the quickly healing long bone fractures of children.

Inverted champagne bottle: the wasting of the legs in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (peroneal muscular atrophy).

Main en griffe describes the claw hand caused by weakness and atrophy of the interosseous muscles of the hand with hyperextension of the metacarpophalangeal joints and flexion of the interphalangeal joints. It results from peripheral nerve lesions pressure palsies, C8/T1 nerve root or plexus damage, or from cord lesions such as motor neuron disease or syringomyelia.

Musician’s cramp or dystonia: disabling episodes of dysfunction of arm or hand muscles experienced intermittently by pianists, violinists, and guitar players. They have been compared to overuse or repetitive strain. Psychogenic factors are, however, seldom absent in what is sometimes claimed to be a segmental dystonia.

Nutmeg liver is the pathological appearance of the liver caused by chronic venous congestion secondary to right heart failure.

Oat cell carcinoma describes the anaplastic cells of bronchogenic cancer.

Pea soup stools of typhoid, red currant jelly stools of intussusception, and rice-water stools of cholera, are reported in gastroenterology.

Peau d’orange: a pitting or puckering of the skin is seen indicating lymphatic blockage in breast ductal carcinoma.

Pill-rolling tremor is a hallmark of Parkinson’s disease: the small repetitive rolling movements at rest (4-6 Hz) of thumbs adducted across the flexed fingers—the movement adopted by pharmacists of old when making tablets by rolling them between thumb and fingers.

Port wine stain is a cutaneous congenital angioma seen in Sturge-Weber syndrome.

Risus sardonicus is seen in tetanus or strychnine poisoning.

Saturday night palsy graphically describes the wrist and finger drop of a radial nerve palsy when the patient has squashed his upper arm by sleeping with it over the back of a chair, or folded under his body when drunk or sedated.

Scrivener’s palsy, or Writer’s cramp (Latin scribere, to write) differs from the common “idiopathic” leg or foot cramp of the middle-aged and elderly. It is a form of focal dystonia owing to sustained muscle contractions, frequently causing twisting and repetitive movements, and abnormal postures. Epidemics were reported in the 1830s among clerks of the British Civil Service, where it was falsely attributed to the new steel pen nib.

Shaking palsy was the name given by James Parkinson in 1817 to his disease characterized by bradykinesia, rigidity, and resting tremor. But the term palsy is metaphorical since true paralysis is not a feature, although voluntary movement is impeded by extrapyramidal dysfunction.

Snow storm is a term applied to a fine nodular interstitial pattern seen on chest x-rays in miliary tuberculosis or disseminated metastases.

St. Vitus’ dance was a popular label for the now rare chorea of rheumatic fever (Sydenham’s chorea, 1686). The name recalls its history. The rapid fine distal jerky movements are associated with hypotonia and suspended or hung-up tendon reflexes—more metaphors. Saint Vitus was a Sicilian alleged to have performed miracles, which made his reputation as the patron saint of neurological disorders. The healing power of the saint’s relics relieved the “unsteady step, trembling limbs, limping knees, and paralysis . . .” signs that mimicked a dance. Pieter Brueghel the Elder in 1564 famously depicted Saint Vitus’ dance in a print, Procession of the Possessed. In 1880 Beard described epidemic chorea, known as the jumping Frenchmen of Maine, now thought to be mass hysteria.

Strawberry tongue: seen in scarlet fever.

The birds and the bees symbolize the talk between parents or teachers with children to inform them about sexual reproduction.

Whiplash injury is a misleading attributive metaphor introduced by Crowe in 1928 for neck sprains or symptoms often after extension-flexion injury, reminiscent of the lash of a pliable whip.

Winged scapula results from lesions of the long thoracic nerve of Sir Charles Bell that innervates the serratus anterior muscle, causing medial transition of the scapula and prominence of its vertebral border. Common causes are trauma, and an acute brachial plexus neuropathy (neuralgic amyotrophy) in which the cause is often unknown.

Yips or golfers’ cramps are jerks, spasms, or freezing of movement while putting or chipping, the rest of the game being relatively unaffected. The problem is variable, stress-related, without clear evidence of organic focal dystonia. Golfers adopt various tricks to overcome this disabling problem with varying success. Players of cricket, baseball, and darts have been similarly affected, and some have to relinquish competitive sport.

Comment

Metaphors are widely used by doctors, but also by patients to improve their ability to give clarity or meaning to their feelings or ideas about a symptom or illness. They often are vivid and dramatic and conjure up a clear image that helps the receiver to both visualize and remember the phenomenon or experience described. Metaphors express relationships of ideas. They are a qualitative leap from a prosaic comparison to something more easily envisaged and remembered. They seldom mislead, confuse, or behave as red herrings.

Further reading

- Bleakley A. Thinking with Metaphors in Medicine: The State of the Art. London and New York, Routledge 2017.

- Morgan G. Images of Organization. SAGE Publications. 1997.

- Lakoff, G, Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2003.

- van Rijn-van Tongeren Geraldine W. Metaphors in Medical Texts. Rodopi. Amsterdam-Atlanta, GA 1997

- Terry SI, Blanchard B. Gastrology: the use of culinary terms in medicine. British Medical Journal 1979; 2:1636

- Roche CJ, P. O’Keeffe DP, Kit Lee W. Duddalwar VA, Torreggiani WC, Curtis JM. Selections from the Buffet of Food Signs in Radiology. RadioGraphics 2002 22:6, 1369-1384

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine

Leave a Reply