Mariella Scerri

Mellieha, Malta

Victor Grech

Pembroke, Malta

|

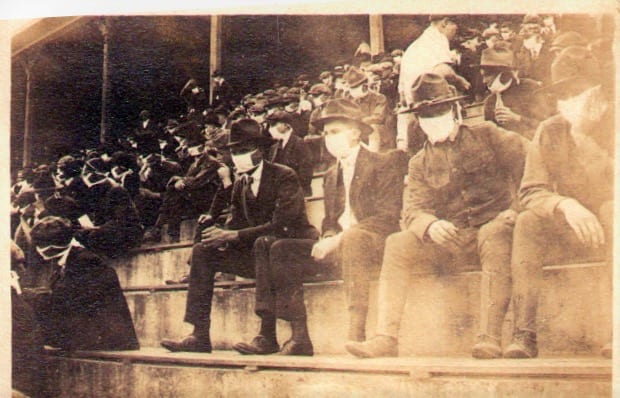

| Photo of the crowd at an undetermined 1918 Georgia Tech home football game. Photo by Thomas Carter, Public domain. Via Wikimedia. |

“Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world; yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky.”1 Albert Camus, The Plague

Experts have long analyzed plans and developed scenarios to respond to an infectious outbreak such as COVID-19. Unfortunately, the public collectively failed to understand the risk and consequences of such a pandemic before it occurred.2 It is natural to feel anxious, fragile, and disoriented in these unprecedented times; anxiety reflects the mind’s effort to control the unknown. In such an unparalleled scenario, art becomes pivotal. There are similarities between the 1918 influenza pandemic and COVID-19, including parallels in the role of art. Understanding the response of artists from a century ago is crucial as we look to draw lessons for the present day.

While the 1918 influenza pandemic transformed everyday life, artists struggled to visualize its true impact. On October 6, 1918, a newspaper spread appeared in cities across the United States that conflated science, art, nationalism, and war. The layout combined scientific diagrams of the human respiratory system with a reproduction of a 1900 painting of a bubonic plague victim by British artist John Maler Collier, a late follower of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood.3 His work featured a finely dressed woman collapsed on the floor of the luxurious interior of a house bathed in oblique light from a large, multi-paned window. A man in the background backs away from the scene, steadying himself against a large tapestry. The woman, beautiful and unmarred, looks as though she has simply fainted rather than fallen victim to contagion. This image of a swooning maiden eradicates from memory the grotesque reality of death by plague, which in reality was rapid, violent, and visually horrid.4 The image, which accompanied an article about the 1918 influenza pandemic by physician Gordon Henry Hirschberg, had a caption that read: “Such Epidemics as [the Plague] which ravaged England and almost all of Europe in the seventeenth and earlier centuries are now impossible, modern medical science having devised infallible means of coping with them. The influenza, bad as it is, is a slight disorder compared to ancient pestilences that followed wars!”5

The use of such a painting in place of a representational image was intended to contain and neutralize public fear, safely encapsulating the disease within medical spheres and relegating it to the distant past. Published nearly one month before the conclusion of World War I, the article nevertheless provided a glimpse of the human costs of a terrifying illness sweeping rapidly across the globe that tested the limits of turn-of-the-century medicine and the efficacy of public health initiatives in increasingly crowded cities.6

Today the world is witnessing yet again how the outbreak of a virulent disease fundamentally changes the way people interact with the urban environment, affecting not only cultural institutions but everyday visual experience. Within days of the World Health Organization declaring COVID-19 a pandemic on March 11, 2020, New York City’s museums, galleries, and theaters closed in rapid succession, followed by the shuttering of school buildings and suspension of all nonessential businesses in the state.7 A century earlier, however, New York had refused to go this far in its public health response. In place of a shutdown, New York launched a public education campaign, flooding the city with circulars, newspaper spreads, magazine articles, posters, and brochures, placing the responsibility on citizens to halt the spread of disease. The Health Commissioner of New York, Royal S. Copeland, refused to close entertainment centers, particularly those “big, modern, sanitary theatres.”8 They remained open both for the morale of the city and for the additional opportunity to share public health information. As Copeland pointed out in a New York Times article, theatrical productions were preceded by announcements explaining how influenza spread and the measures audience members could take to protect themselves. Copeland argued that keeping theaters open would “protect the public from a condition of mind which would predispose it to physical ills.”9 He was one of many who viewed cultural institutions and activities as a way to prevent the spread of influenza by maintaining the psychological health of the population.

Conversely, current mitigation measures are aimed at preventing physical interaction. Museums and theaters have transferred many of their programs to digital spaces with the aim of calming the minds of a troubled population. Easily accessible, low-cost therapeutic activities such as art therapy that promote self-care and a healthy outlet for heightened emotions are essential. Art therapy may reduce feelings of isolation, acknowledges the inherent need for autonomous expression, and creates an outlet for such expression and an opportunity for deep introspection.10 When exposure to outside elements is limited and isolation hinders social interactions, such expression is all the more useful in creating routines for self-care and mindfulness, as well as healthy outlets to cope with symptoms of trauma. These emotional outlets and routines to build self-awareness “can proactively help support individuals who are inclined toward depression/ depressive episodes.”11

In the annals of cultural history, the flu of 1918 is little more than a historical footnote. The most commonly cited reason for this is the enormous impact of World War I. The flu took hold in January 1918, about ten months before the war ended. Although the highest estimates for the number of dead from the disease (around 50 million) outnumber the high estimates for those killed in the war (around 40 million), the far-reaching political and social implications of the global conflict have taken precedence in the macro-history of the twentieth century.12 Artists, too, were more drawn to depictions of the war and their paintings speak to an almost universal fascination with its cataclysmic impact.

There are only a few notable artworks recording the influenza pandemic. Edvard Munch, one of the most recognizable names to have been infected, had long been fascinated with terminal illness. Tuberculosis traumatized Munch’s early years and fueled his lifelong journey through the vagaries of the human condition. He made two noteworthy depictions of the effects of influenza: the disquieting Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu (1919) and the more macabre Self-Portrait after the Spanish Flu (1919–20).13 In the second painting the tormented painter appears to be both judge and victim of this pandemic killer. The terse yet unsteady demeanor, the puffy discolored glare, and the quivering lines of fever and chills highlight the despair and isolation of the “grippe” patient in his oppression, weakness, malaise, lack of air, stupor, and hopelessness. These paintings, with their queasy colors and undulating lines, hollowed-out faces and undefined or unfocused eyes, are arguably more about Munch’s psychology and self-mythologizing than the painful experience of the flu itself.14 No cyanosis is visible, no implements of care are seen; indeed, one would not know that Munch was infected were it not for the titles.

More compelling is a quick portrait sketch that Egon Schiele made of his wife, Edith, the day before she died of the flu, and a few days before the artist’s own death of the same at age twenty-eight.15 Edith’s face is gaunt and drawn, the shading of her cheeks and lips perhaps a sign of cyanosis. Yet again, while the pictorial treatment is slightly less romanticized than Munch’s, the young woman’s soulful eyes and chaotic strands of hair signal that this is a psychological portrait rather than a clinical reflection of a rapidly debilitating disease. One might substitute any cause of suffering, much as plague replaced influenza in Collier’s painting.16 Egon Schiele’s 1918 painting The Family, which depicts the artist, his wife, and a baby was never finished: Schiele and his spouse died from the flu before he could complete the work. Schiele was at the peak of his career in 1918—“he had his first really successful exhibition in March of that year, his wife was pregnant with their first child, and he had rented a big studio in the summer.”17

A special exhibition called “Spit Spreads Death” has gained newfound resonance as people look to draw lessons for today.18 Trevor Smith, a curator at the Peabody Essex Museum, commissioned a collective called “Blast Theory” to commemorate the 1918 pandemic. He organized a 500-person parade, which took place on Broad Street in Philadelphia in September 2019. Marchers held signs with the names of victims and healthcare workers who died, referencing a parade of 200,000 people that took place in the city in 1918 and greatly exacerbated the number of cases in the city, leading to an untold number of deaths.19

When the performance took place, Smith says he reflected on “just how lucky we were to not be facing that crisis.”20 In a matter of months, however, the situation had drastically changed. While it is still too early to say how new art will reflect the current pandemic, art has nonetheless been flourishing. From performers tapping into their creativity to relay health guidelines and share messages of hope, to neighbors singing to each other on balconies, to concerts online—creativity abounds. Even the Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci’s most famous masterpiece, has been re-imagined as self-isolating in the Louvre Museum or covering her enigmatic smile with a surgical mask.21

Paying tribute to the solidarity shown by artists and institutions at a time when “art is suffering the full force of the effects of a global health, economic and social crisis,” UNESCO Director General Audrey Azoulay flagged this time of confinement as “a period of openness to others and to culture, to strengthen the links between artistic creation and society.”22 The coronavirus pandemic has closed museums and canceled concerts, plunging many cultural institutions into uncertainty and immediate financial loss while also threatening a long-term effect on the arts. Keeping art alive requires a twofold approach: supporting cultural professionals and institutions, and promoting access to art for all. These challenges require far-reaching cultural policies and it will be necessary to “listen to the voices of the artistic world in their globality and diversity.”23

The wide-reaching effects of the current pandemic will be felt for years to come, and many people are in need of reassurance and comfort in this time of uncertainty and change. This urgently requires creativity, reimagining, and innovation. People have produced great works of art throughout history, and the same will happen today. There are far more questions than answers right now, but the persistent “strong impetus for culture” will prove that even in a period of personal distancing, “art brings us closer together than ever before.”25

Notes

- Albert Camus. The Plague. (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1948).

- Kostas Kostarelos. “Nanoscale nights of COVID-19”, Nature Nanotechnology, 15 (2020): 343 -344.

- Audrey Knox. “The Spanish Influenza transformed everyday life. But artists struggled to visualize its impact”, Art in America,

- Knox.

- Knox.

- Knox.

- Knox.

- “Epidemic Lessons Against Next Time: Dr. Copeland Tells Why New York Got Off Easier Than Other Cities—Pays Tribute to Predecessors,” New York Times, Nov. 17, 1918, p. 42.

- Letter from Royal S. Copeland to National Association of the Motion Picture Industry, quoted in Aimone, “The 1918 Influenza Epidemic,” (December 1918): 77.

- F Ceausu. “Fine arts: The healing power of art-therapy”, Review of Artistic Education, 16 (2018): 203–211. https://doi.org/10.2478/rae-2018-0022

- Mallory Braus and Brenda Morton. “Art Therapy in the Time of COVID-19”, Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12 No 1 (2020): 267-268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tra0000746

- Taylor Dafoe. “The 1918 Spanish Flu Wreaked Havoc on Nearly Every Country on Earth. So Why Didn’t More Artists Respond to It in Their Work?”, Art Net News, 2020 https://news.artnet.com/art-world/spanish-flu-art-1836843

- Dafoe.

- Jay A. Clarke, “Creating a Reputation, Making a Myth,” Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety and Myth, exhibition catalogue, Art Institute of Chicago, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009).

- Michael Lobel. “Close Contact”, Artforum,

- Dafoe.

- Dafoe.

- Dafoe.

- Dafoe.

- Dafoe.

- Eric Ganz. “Even during COVID-19, art ‘brings us closer together than ever’ – UN cultural agency”, Culture and Education,

- Audrey Azoulay. “RESILIART Artists and Creativity beyond Crisis”, UNESCO,

- Azoulay.

- Azoulay.

Bibliography

- Azoulay, Audrey. 2020. “RESILIART Artists and Creativity beyond Crisis”, UNESCO, 2020.

- Braus, Mallory and Morton, Brenda. 2020. “Art Therapy in the Time of COVID-19”, Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12 No 1: 267-268.

- Camus, Albert. 1948. The Plague. (London: Hamish Hamilton).

- Carr, Susan. 2020. “Art therapy and COVID-19: supporting ourselves to support others”, International Journal of Art Therapy, 25 No 2: 49-51.

- Ceausu, F. 2018. “Fine arts: The healing power of art-therapy”, Review of Artistic Education, 16: 203–211. https://doi.org/10.2478/rae-2018-0022

- Clarke, J.A. 2009. “Creating a Reputation, Making a Myth,” Becoming Edvard Munch: Influence, Anxiety and Myth, exhibition catalogue, Art Institute of Chicago, (New Haven: Yale University Press).

- Dafoe, Taylor. 2020. “The 1918 Spanish Flu Wreaked Havoc on Nearly Every Country on Earth. So Why Didn’t More Artists Respond to It in Their Work?” Art Net News. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/spanish-flu-art-1836843

- Ganz, Eric. 2020. “Even during COVID-19, art ‘brings us closer together than ever’ – UN cultural agency”, Culture and Education.

- Knox, Audrey. 2020. “The Spanish Influenza transformed everyday life. But artists struggled to visualize its impact”, Art in America.

- Kostarelos, Kostas. 2020. “Nanoscale nights of COVID-19”, Nature Nanotechnology, 15: 343 -344.

- Lobel, Michael. 2020. “Close Contact”, Art Forum.

MARIELLA SCERRI, BSc, BA, PGCE, MA, is a teacher of English and a former cardiology staff nurse at Mater Dei Hospital, Malta. She is reading for a PhD in Medical Humanities at Leicester University and a member of the HUMS program at the University of Malta.

VICTOR GRECH, MD, PhD, FRCPCH, FRCP, DCH, is a consultant pediatrician to the Maltese Department of Health, and has published in pediatric cardiology, general pediatrics, and the humanities. He has completed PhDs in pediatric cardiology and English literature. He co-chairs the HUMS program at the University of Malta.

Leave a Reply