F. Gonzalez-Crussi

Chicago, Illinois, USA

Of all bodily parts, the head has traditionally enjoyed the greatest prestige. The Platonic Timaeus tells us that secondary gods (themselves created by the Demiurge) copied the round form of the universe to make the head, divinest part of our anatomy. In order to avoid its rolling on the ground like a bowling ball (what an insufferable affront this would be!), the gods furnished it with a body. Thus, the entire body is nothing but a conveyance for the head’s displacements: a mere hackman, so to speak, to His Cephalic Majesty. Inveterate reasoners that they were, the Greeks naturally conferred the highest importance to the head, for it is “the seat of counsel,” i.e., the residence of reason, intellect, and judgment.

The material substratum of these faculties is the brain, which lies inside an osseous receptacle, the cranium or skull. This one had to be an excellent structure: one does not put up a royal guest in second-class accommodations. Accordingly, the skull was shaped as a sphere, which the Greeks deemed the most perfect of geometric shapes. God had to be round: Xenophanes and Parmenides propounded the notion of a rotund deity. The theologian Alain de Lille, (Alanus de Insulis, by his Latin name) re-discovered the idea in the twelfth century and enunciated it in an obscure formula that was repeated (although probably never quite understood) for centuries: “God is an intelligible sphere whose center is everywhere and its circumference nowhere.”

Later ages adopted radically different philosophical schemes, yet in no way diminished the importance of the head. The soul was thought to reside inside the cranium, although precisely where in that spheroidal shelter, no one knew. Scholars often evaded this question. Or else they supplied blurry, imprecise bearings, like “the sensorium commune,” which was like saying that it was nowhere and everywhere inside the brain. Only Descartes had the guts to pin-point it to the pineal gland, using rather interesting arguments that no one cares for anymore.

Before the rise of rationalism, the skull was thought to retain some of the force of the spirit that departed at the time of death. As a consequence, the skull was said to have therapeutic properties. Apothecaries had in stock various skull-based preparations. Powdered skulls of recently executed criminals were held to be most efficacious for the treatment of epilepsy. King Christian IV of Denmark suffered this disease and took the treatment; with what result, I do not know. Best of all were the skulls on which moss and lichen had grown. In 1694, London druggists were selling mossy skulls for 8 to 11 shillings each, depending on the size of the cranial bones and the amount of moss present. The moss scraped off the bone could be used internally or externally. A New England physician wrote toward the end of the seventeenth century that “moss in the skull of a dead man … stops bleeding. Some say if it be held in the hand it stops it like an enchantment.”1 The moss generally sold was of the genus Usnea. A medical dictionary of the English naturalist Robert James (1703-1776) noted, under the entry Usnea Cranii humani, that its virtues are enhanced “when the moon enters Virgo. Others favor Taurus, Gemini, and Pisces.”2 To collect mossy skulls found in cemeteries or other burial sites by the moonlight must have added a note of mystery and esotericism, which assuredly did not mar the popularity of this remedy. Belief in the healing powers of moss- and lichen-covered skulls persisted until the nineteenth century. Incredible as it seems, as late as the early twentieth century, German pharmaceutical handbooks listed “mummy,” i.e., pieces of embalmed cadavers, skull, as well as flesh from Egyptian mummies (but in reality most of them fake), at 17 marks and 50 pfennigs per kilogram.3

The fascination with the skull’s ineffable, preternatural powers has much to do with the horrible practice of decapitation. Soldiers in war have ever decapitated their foes. The greatest injury that could be inflicted upon an enemy is to sever his head. It is to deprive him of his physical identity (the face) and his moral self, for the head is the storehouse of all his dreams, thoughts, and feelings. Historically, the armies of the Ottoman Empire excelled at “cephalic harvesting.” Soldiers of the Ottoman Empire during their campaigns in Eastern Europe decapitated 28,000 foes in one battle, and 40,000 in another. The heads were dumped in front of the pasha’s tent, where they formed “pyramids” or towers “as tall as minarets” that grew gradually as the battle raged on.4

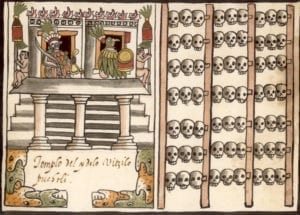

Between the fourteenth and the sixteenth centuries, as the Ottomans were busy lopping off heads, a wholly foreign people in remote lands across the ocean without any connection to the Turkish warriors, engaged in the identical activity. The Aztecs of Mesoamerica decapitated the enemy, peeled the skull, cut holes in each temporal region, and passed through the perforations a long wooden rod on which other skulls had already been equally “skewered.” The long row of skulls thus formed, added to other rows similarly constructed, the notorious Aztec tzompantli or “skull rack.” (Fig. 1) Enemy heads thus displayed by the thousands struck terror in the hearts of the Spanish conquistadors.

American soldiers decapitated the enemy, mostly the Japanese, during the Second World War.5 Unable to build skull pyramids, minarets, or tzompantli, they settled for collecting teeth, fingers, ears, etc. as take-home war trophies. But now and then they honored the ancient head-severing tradition. To believe anthropologists and historians, at one time or another all societies in the world, without exception, have practiced decapitation.

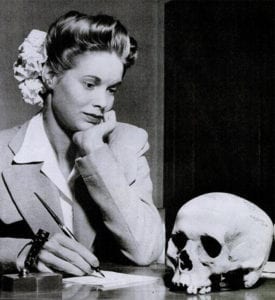

An American soldier sent the cranium of a dead Japanese foe to his fiancée. Allegedly, he had promised it to her, however unlikely this choice may seem as a token of amorous devotion. The popular magazine Life published a photograph of the young lady sitting by the gift and writing a thank you letter to her beau. A young, pretty woman next to a human skull makes an unusual image. Art has accustomed us to expect instead a gaunt, emaciated male mystic doing penance. Yet a young female side-by-side with a skull constitutes a well-known motif in pictorial representations of the repentant Magdalen, among which the incomparable work of Georges de la Tour (1593-1652) deserves a special place. I cannot resist comparing it to the Life photograph. (Fig.2).

La Tour’s Magdalen (here shown one of the three he painted) is immersed in a fantastic gloom. It is a play of lights, which lacks the vividness, the fire, or the genial savagery of Caravaggio’s gripping chiaroscuro. Instead, La Tour’s darkness confers to the scene a certain dignity, an imposing gravity uniquely fitting to spiritual meditations. The skull is placed on her lap, and she poses her right hand upon it. We feel drawn into Magdalen’s lacerating inner drama of self-denial and repentance.

1944 issue.

The American young lady, in contrast, is fully illuminated. The scene is clearly contrived. She is posing, dressed to the nines in the fashion of the 1940s: not one hair out of place. Who can believe that she was surprised while spontaneously writing a letter to her boyfriend? The photograph caused a furor in Japan. The Nippon press thundered against the barbaric brutality of Americans, who so insensitively publicized the human remains of a vanquished foe, in callous disregard of international agreements and of elementary decency. Truth to tell, the Japanese were no paragons of warfare chivalry themselves: their active role in heinous war crimes has been amply documented. But the message of the American photograph was plain. The well illuminated, well focused skull proclaimed: “This is what happens to whosoever challenges us or what we stand for.”

La Tour’s Magdalen conveys a different message: one of renunciation and repentance. The unspoken voice of art rises in the night, amid the silence, to remind us of the brevity of our lives and the futility of our strivings. A critic once remarked that “great art says something that is said nowhere else, not in another century, or in another country.”6 But perhaps it is not the “message” that counts, for the “content” is always conjectural (our conjecture). La Tour’s painting moves us because it makes us feel that the scene is about to say something extraordinary that grows from the fourfold root of piousness, misfortune, suffering, and repentance. Only this something is like music, which cannot be articulated with words. Or like something about to be said, but which never breaks forth. Borges wrote that this “imminence of a revelation, which is not produced, is the true esthetic fact.”

References

- Frances Larson: Severed. A History of Heads Lost and Heads Found. Liveright Publishing Corporation. London. 2014, pp. 152-153.

- P. Modenesi: “Skull lichens: A curious chapter in the history of phytotherapy.” Fitoterapia 80: 145-148. 2009.

- Frances Larson: Severed (Loc. cit.), p. 154.

- Paul-Henri Stahl: Histoire de la Décapitation. Paris. Presses Universitaires de France. 1986,

- Simon Harrison: “Skull Trophies of the Pacific War. Transgressive Objects of Remembrance.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, new series, 12: 817-836; 2006.

- André Fermigier: “Un dieu de la peinture pure.” Le Nouvel Observateur no. 392: 1972.

- Jorge Luis Borges: In “La muralla y los libros” Chapter 1 in: Otras Inquisiciones. Alianza Editorial. Madrid, 2002, p. 13.

FRANK GONZALEZ-CRUSSI, MD, now retired, is Emeritus Professor of Pathology of Northwestern University Medical School. He has authored numerous publications of both medical and literary character, as listed in Wikipedia.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 11, Issue 4 – Fall 2019

Leave a Reply