Atara Messinger

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

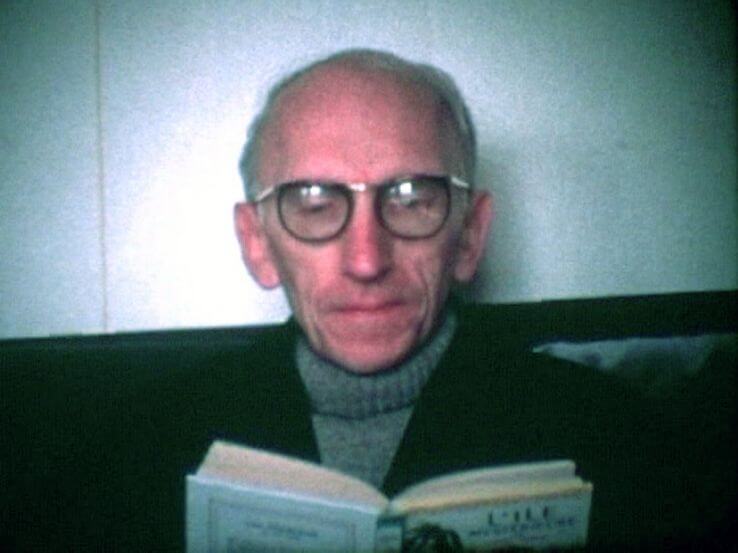

Maurice Blanchot (1907–2003)

I wheeled the patient through the double doors into the operating room. As I parked the hospital bed next to the operating table, I quickly glanced at the patient’s chart. NAME: ‘J.’ AGE: 28. HISTORY: Progressive headaches, visual changes, and right-sided weakness. IMAGING: MRI of the brain shows contrast-enhancing mass with hypointense core.

Lying on the operating table waiting to be put to sleep, the patient looked surprisingly calm. I wondered if I was more nervous than he. I was a third-year medical student scrubbing for my first craniotomy. My role was minimal, but I was terrified: of making a mistake, of not knowing enough, of betraying my fear. The knot in my stomach eased as I gave myself over to the intense reality of the scene.

As the anesthesia team prepared their equipment, I watched the patient as he talked with one of the nurses. Although I could not make out what he was saying, his voice was steady and his expression confident.

Once the set-up was complete, the anesthesiologist injected a milky white solution into the patient’s left arm. Within seconds, a previously sturdy and aware young man went limp. With a concerted effort, the anesthesiologist took hold of the patient’s head and extended it backwards, then downwards. Applying pressure to the jaw, she popped open the mouth and inserted the breathing tube connected to the machine that would function as his lungs.

I was given the initial task of shaving off a patch of hair on the left side of the patient’s head. I stepped to the side as the neurosurgery resident followed the path of my razor blade with his scalpel, cutting into the skin overlying the skull. The path completed, he turned over the flap of skin, and picked up the drill. Several minutes later, the brain was exposed.

“Wow,” said the resident.

My eyes widened; I had never seen a brain before. “What?” I whispered.

The resident switched into another gear, speaking and moving with alacrity. “Take a look at that. Let’s get a biopsy. My guess is GBM.”

Glioblastoma multiforme. It is one of the most aggressive forms of brain cancer with no definitive cure and an estimated fourteen-month survival rate.

In that moment, I looked at the patient lying on the operating table: with part of his brain exposed to the world, he could not have appeared more vulnerable. Strangely, this sight drew me in. Not unlike Leontius who, as Plato recounts in the Republic, finds himself lured by the sight of dead bodies next to an execution ground, I looked, again and again, at the sight of J. lying like a corpse on the operating table, and focused on the exposed lump of cells with mysterious curiosity.1 I remember this vividly because in that moment, I felt nothing.

Susan Sontag, in her work Regarding the Pain of Others, writes that “Shock can become familiar. Shock can wear off. Even if it doesn’t one can not look.”2 It is paradoxical that in some sense, modern medicine has enhanced our ability “to look” at our patients in remarkable ways. From MRI scans to surgical lenses, medical technology has given us the power to quite literally see through our patients, to visualize everything from their inner organs to their individual cells. At the same time, one might ask if we have zoomed in too far. In gaining the ability to see into the innermost reaches of the body, have we lost sight of the bigger picture—have we stopped seeing the whole person in front of us?

The results of J.’s biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of GBM, and J. was kept in hospital post-operatively for a short-term stay. My task was to assess him every morning. On my second visit, I noticed a thin book resting on his lap. Notes from Underground by Dostoevsky.

“Dostoevsky?” I asked inquisitively.

“Dostoevsky . . .” He repeated and turned to look at me with a gentle smile. “He teaches us about suffering. About the possibility of accepting, even embracing, suffering.”

I knew what he was saying, but I asked: “Why would we want to do that?”

He sighed, folded his arms, and leaned back in the hospital bed. “Because in suffering . . . you meet yourself. You peel away the layers, and you come out of hiding. I am in pain, and I know I am going to die. But instead of running, of becoming numb, I am allowing myself to feel.” I took his hand, and held it for a moment before I left his room.

I wished I had been able to convey some aspect of who J. really was when reporting on his “status” to the neurosurgery team. Instead, I found myself mechanically reciting my clinical observations: The GBM in Room 9 appears vitally stable. Persistent headache, 8/10 intensity. Some nausea, no vomiting. Urine output 40 cc.

In his text “Literature and the Right to Death,” French literary theorist and philosopher Maurice Blanchot writes about the objectifying power of language—an idea that can shed light on the role of diagnosis in clinical medicine. Blanchot theorizes that “When we speak, we gain control over things with satisfying ease.”3 He proposes that the act of naming—of defining a being through words—cannot adequately capture a being’s inherent essence. In this way, “A word may give me its meaning, but first it suppresses it.”4 Blanchot provides an example: the process of naming a being “this woman,” for instance, means that “this person who is here right now, can be detached from herself, removed from her existence and presence, and suddenly plunged into a nothingness.”5 In this way, in the process of naming her, I “take her flesh-and-blood reality away from her, cause her to be absent, annihilate her.”6

Blanchot’s ideas raise interesting questions about the relationship between diagnosis and identity in clinical medicine. In today’s medical era, the boundary between the patient and the diagnosis is sometimes blurred. This is reflected, among other ways, in the language we use to describe patients—“the diabetic,” “the schizophrenic,” or in our case, “the GBM in room 9”—as if the patient and the disease become one. One problem with this type of approach is that it can serve to dialyze the humanity and particularity out of the patient in front of us. In my own case, in defining J. through his disease, in paying more attention to his symptomatology than to his humanity, did I not “retain nothing of [him] but [his] absence, what [he] is not”7 and thus render him “an objective, impersonal presence?”8

My experience with J. opened my eyes to the possibility that today’s medical education system may be reinforcing strategies that help us “not look” at the whole patient, that help the shock wear off. Indeed, as medical trainees, we are often warned, in both the formal and “hidden” curricula, about the importance of remaining detached and about the dangers of feeling too much. This approach, no doubt, has merit. If we were to constantly see our patients as whole beings, if we were to ceaselessly take on their suffering, we might become overwhelmed, experience compassion fatigue, and ultimately burn out.

But what is curious to me is why we are far less readily warned about the opposite side of the coin: about the dangers of not feeling enough, and how not feeling and not looking can lead to burnout, too. While making room to look at and listen to the individual who lies beneath the diagnosis may disrupt our “ease and security” in medicine, and may insert confusion and ambiguity into an otherwise structured and categorized system, it may also help doctors regain a sense of meaning, if not feeling, in the practice of medicine.9

Ten months after being discharged from hospital, I learned that J. passed away in his home. If I could write J. a note from above-ground, it would read:

Thank you, J., for reminding me to feel.

The details of this story have been changed to protect patient confidentiality.

Notes

- Republic, trans. C.D.C Reeve (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2004), 440a-b.

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), chap. 5.

- Maurice Blanchot, “Literature and the Right to Death,” in The Work of Fire Charlotte Mandel (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995), 322.

- Blanchot, “Literature and the Right to Death,” 322.

- Blanchot, “Literature and the Right to Death,” 323.

- Blanchot, “Literature and the Right to Death,” 322.

- Blanchot, “Literature and the Right to Death,”

- Blanchot, “Literature and the Right to Death,” 325.

- Blanchot, “Literature and the Right to Death,” 322.

ATARA MESSINGER is currently a medical student at the University of Toronto. She obtained her BArts &Sci. from McMaster University and recently completed a Master’s degree in Philosophy at Tel Aviv University. Her research interests include the history and philosophy of medicine, and the role of the humanities in medical practice and education.

Leave a Reply