Lenny Grant

Syracuse, New York, United States

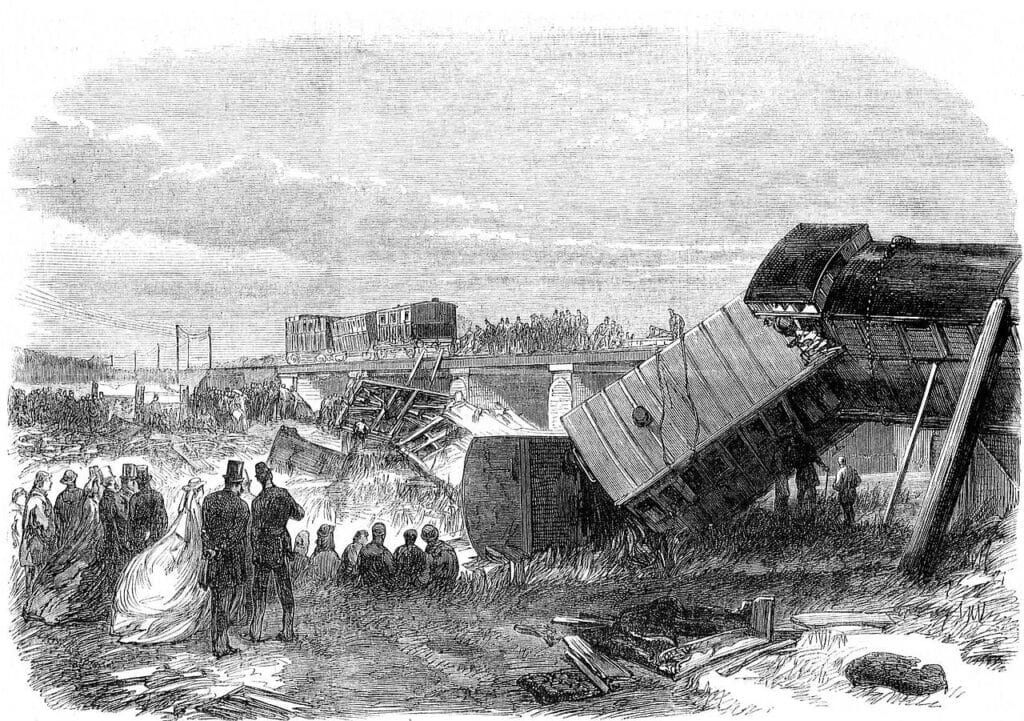

By 1864, British railways were responsible for 36 deaths and 700 injuries annually.1,2 Yet the most perplexing cases were not the visibly wounded, but those passengers who walked away apparently unharmed, only to develop debilitating symptoms days or weeks later.

These survivors experienced what the Lancet described as “disturbed and diminished sleep, frequent starting when dozing, dreams of collisions, noises in the ears, feverishness, feeble pulse, much pallor.”3 Others suffered paralysis, tremors, memory loss, and personality changes so profound that their families scarcely recognized them. One victim who reported no injury at the time of collision was forced to abandon work the following day because “the countenances of his fellow-passengers, with terrified eyes, would come before him whenever he attempted to do any reading or writing.”4 Perhaps the most famous sufferer was Charles Dickens, who survived the 1865 Staplehurst rail disaster and documented his subsequent anxiety, nightmares, and phobic avoidance of train travel in letters to friends—symptoms that never fully abated.5

When these individuals sought compensation from railway companies, they created a legal and medical conundrum. The Campbell Act of 1846 had established that railway companies bore responsibility for passenger safety, and an 1864 amendment strengthened these protections.6 British courts were equipped to adjudicate visible injuries but utterly unprepared for claims involving invisible wounds. Judges and juries needed expert guidance: Were these passengers genuinely injured, or were they malingerers exploiting wealthy corporations? The courts called upon surgeons to answer, and in doing so, created the conditions for “railway spine” to emerge as a formal diagnosis.

Dueling theories

The medical community split bitterly. Surgeon Frederic C. Skey, lecturing at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in 1857, was skeptical. He lamented that legal courts were ill-suited for adjudicating medical facts and worried that lawyers’ “forensic power” could “make the worse appear the better reason.”7 Skey introduced a figure that would haunt trauma medicine for generations: the malingering opportunist. He described a man struck by a baggage cart who demanded compensation for “concussion of the brain and spine,” yet subsequently went snipe shooting and rowing on turbulent seas. Despite Skey’s skeptical testimony, the plaintiff recovered £2,000.8

The tide turned in 1866 when John Eric Erichsen, surgeon at University College Hospital London, published On Railway and Other Injuries of the Nervous System. Erichsen’s approach was rhetorically brilliant. Rather than dismiss railway spine as fraud, he argued it was merely a modern manifestation of an ancient condition called “concussion of the spine.” He traced the diagnosis back to 1766, when a French military officer’s carriage tumbled down an embankment; the Count de Lordat walked away but developed progressive neurological symptoms over four years until his death.9 By connecting railway accidents to pre-industrial trauma, Erichsen removed the taint of modernity and compensation-seeking. Railway spine victims belonged to an ancient lineage of trauma survivors.

To explain how minor jolts produced major symptoms, Erichsen deployed memorable metaphors. He compared the body to a pocket watch: “A watchmaker once told me that if the glass was broken, the works were rarely damaged; if the glass escapes unbroken, the jar of the fall will usually be found to have stopped the movement.”10 External appearance bore no relationship to internal damage. Even more evocatively, he compared the nervous system to a magnet struck by a hammer, its invisible force “jarred, shaken, or concussed out.”11 This appeal to scientific mystery acknowledged medicine’s limits while asserting the condition’s reality.

Erichsen’s somatic theory—that microscopic lesions to the spinal cord caused psychological symptoms—proved extraordinarily difficult to challenge. No technology existed to examine a living patient’s spinal cord. He could posit invisible “molecular derangements,” and no opponent could definitively prove him wrong. His theory crossed the Atlantic, where American courts cited On Railway and Other Injuries extensively in compensation cases. As the New York Times reported in 1866, railway spine had become “a new disease” of considerable interest to “every railway director, manager and working official, as well as to the multitude of passengers.”12

The functional challenge

Not everyone accepted Erichsen’s organic explanation. Herbert William Page, surgeon to the London and North-West Railway, proposed in 1885 that railway spine was a functional disorder—a problem of how the nervous system operated rather than structural damage to tissue.13 Page argued that fear alone could produce all the symptoms Erichsen attributed to spinal lesions. He described a railway employee found in “a state of collapse” after supposedly having his foot run over by a train. Upon examination, “the only damage was the dexterous removal of the heel of his boot by the wheel of a passing engine.”14 The man’s terror, not physical injury, had produced his symptoms.

This debate between somatic and functional explanations—between those who located trauma in damaged tissue and those who traced it to psychological processes—proved remarkably durable. The same controversy would erupt during World War I, when physicians confronted thousands of soldiers exhibiting “shell shock.” Early neurologists hypothesized that proximity to explosions caused microscopic brain lesions, echoing Erichsen. Only when battlefield psychiatrists demonstrated that soldiers who had never been near explosions developed identical symptoms did psychological explanations gain ground.15

The railway spine debate awaited technological resolution. When Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays in 1895, physicians became able to visualize the spine in living patients. Francis X. Dercum, a prominent American neurologist, used autopsy studies and the new radiographic technology to investigate railway spine systematically. His research helped dispel the notion that functional symptoms necessarily indicated structural spinal damage. In two detailed case studies, Dercum found that despite years of debilitating symptoms, “careful microscopic examination of the brain and cord gave no decided result”—no lesions, no inflammation, nothing to support Erichsen’s theory.16 The diagnosis that had dominated medico-legal discourse for decades began its slow fade.

The patient’s silence

What railway spine sufferers themselves thought of these debates remains largely obscured. Victorian medical literature privileged physicians’ expertise over patients’ self-knowledge; case reports filtered experience through professional interpretation. Newspaper accounts focused on accidents and legal proceedings rather than phenomenology. Dickens’s letters offer rare glimpses of subjective suffering, but even literary genius struggled to explain the strange persistence of terror long after danger had passed.

This epistemic asymmetry—doctors theorizing, patients testifying, courts adjudicating, but no one quite capturing the experience itself—would characterize trauma medicine for the next century. The diagnosis emerged not from pure scientific observation but from negotiations between suffering passengers, expert physicians, skeptical corporations, and institutional demands. Railway spine was constructed as much as discovered.

Legacy

By the early twentieth century, railway spine had largely disappeared, overtaken by shell shock and Freudian psychiatry. But its influence persists. The diagnosis established precedents for how we think about psychological trauma today: that invisible injuries deserve legal remedy, that symptoms may appear long after precipitating events, and that the circumstances of injury matter as much as the injury itself.

When the Lancet ran “Discarded Diagnoses: Railway Spine” in 2001, mere weeks before the events of September 11, the author noted that historians “like to see railway spine as part of the historical continuum that stretches through shell shock to post-traumatic stress disorder.”17 Thousands of survivors would soon navigate legal systems requiring medical validation of psychological suffering—systems whose foundations were laid by Victorian surgeons arguing about train wrecks.

Railway spine reminds us that every diagnosis has a biography. The passengers who walked away from nineteenth-century accidents, only to find their lives shattered by invisible wounds, bequeathed us a complex inheritance: the recognition that psychological trauma is real, that it deserves acknowledgment, and that proving its existence requires persuasion as much as science.

References

- Winn C. First fatalities. History Today. 2012;62(9).

- Camps W. Railway Accidents or Collisions. London: H.K. Lewis; 1866:6.

- The influence of railway travelling on public health. Lancet. 1862;79(18 January):79-84.

- “The influence of railway travelling,” Lancet, 155-158.

- Trimble MR. Post-Traumatic Neurosis: From Railway Spine to Whiplash. London: John Wiley & Sons; 1981:27.

- Schivelbusch W. The Railway Journey. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1986.

- Skey FC. Clinical lecture on concussion of the spine. Lancet. 1857;69(1741):27.

- Skey, “Clinical lecture,” 28.

- Erichsen JE. On Railway and Other Injuries of the Nervous System. Philadelphia: Henry C. Lea; 1866:24-26.

- Erichsen JE. On Railway and Other Injuries. 1866:73.

- Erichsen, On Railway and Other Injuries, 73.

- “The ‘Railway Spine’—A new disease.” New York Times. October 15, 1866:2.

- For a detailed biography of Page, see: Davidson J. Herbert William Page and the railway spine controversy. Hektoen International Summer 2022.

- Page HW. Injuries of the Spine and Spinal Cord without Apparent Mechanical Lesion. 2nd ed. London: J. & A. Churchill; 1885:162.

- Jones E, Wessely S. Shell Shock to PTSD: Military Psychiatry from 1900 to the Gulf War. Hove: Psychology Press; 2005.

- Dercum FX. “Two cases of ‘railway-spine’ with autopsy.” Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 1895;20(8):481-496.

- Bynum B. “Discarded diagnoses: Railway spine.” Lancet. 2001;358(9278):339.

LENNY GRANT is an assistant professor of writing and rhetoric at Syracuse University, where he teaches technical writing, medical rhetoric, and health humanities. He is the founder of the Resilience Writing Project, which teaches the healing modalities of writing. His monograph, Diagnosing Justice: Psychological Trauma and the Rhetoric of Repair, is forthcoming from University of Alabama Press.

Leave a Reply