JMS Pearce

Hull, England

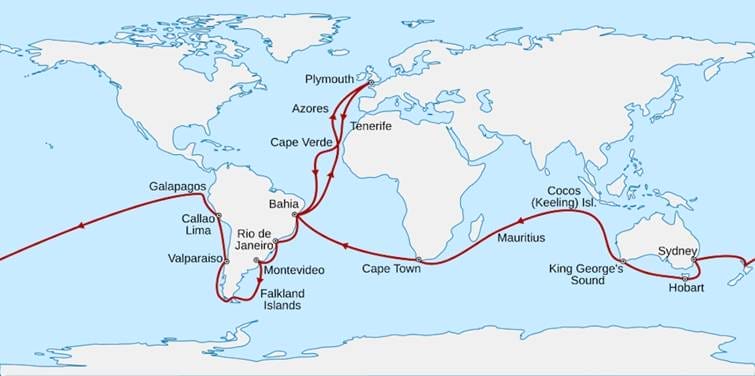

Charles Darwin (1809–1882) for much of his life was subject to illness and periods of invalidity. Their cause has been widely debated.1 Darwin joined the second voyage of HMS Beagle in December 1831. Under Captain FitzRoy, its prime purposes were to study weather systems and to survey and chart new territories. It ended five years later in 1836. During the voyage Darwin was often incapacitated by periods of illness, about which there is surprisingly little published medical detail.

Before the famous voyage of the Beagle, Darwin briefly studied medicine at Edinburgh University from 1825 to 1827, then took a Bachelor of Arts degree at Cambridge in 1831 where he collected beetles and acquainted himself with natural philosophy, botany, and theology. His interests were wide, and he studied assiduously the works of the eminent scientists: John Stevens Henslow, Adam Sedgwick, William Paley, Humboldt, Herschel, and James Stephens.

Henslow, Professor of Mineralogy and Botany at Cambridge, wrote to Robert FitzRoy, captain of HMS Beagle, commending Darwin for his forthcoming expedition2:

I know hardly anyone so well fitted for the undertaking. He is a young man of promising ability, extremely fond of natural history, and well qualified for collecting, observing, and noting anything worthy to be noticed in natural history.

The conditions encountered by Darwin and the crew were far removed from the tranquil walks of Cambridge. During the voyage they had to endure long periods at sea, the hazards of tropical and subtropical South America, and arduous expeditions. The Beagle and its crew visited regions infested with malaria, yellow fever, typhoid, Chagas’ disease (Trypanosoma cruzi), and dysentery.

Darwin suffered recurrent bouts of seasickness and prostrating exhaustion during the voyage. He was often incapacitated for days at a time. What medical attention did he receive?

HMS Beagle’s doctors

Robert McCormick (1800–1890) was a naturalist and a Royal Navy surgeon who joined the Beagle at the start of the voyage (1831); but he felt that Darwin had usurped his role as a naturalist, which caused a dispute with Captain FitzRoy. Consequently, McCormick left the voyage in 1832. Darwin remembered Robert McCormick as a man of “much ability but little sympathy.” He was replaced by Benjamin Bynoe (1804–1865) MRCS (later FRCS by election 1844), a naval surgeon and naturalist. Initially appointed assistant surgeon, he held the post of acting surgeon on the Beagle from April 1832 until the end of the voyage.

Bynoe became Darwin’s friend. He often accompanied him on expeditions. In the Galapagos Islands Darwin made the observations and collections that led to his theory of evolution by natural selection.* He and Bynoe while ashore studied geology, marine and land animals including lizards, tortoises, finches, insects, as well as numerous plants; they both collected and dispatched hordes of specimens, many stored by Henslow, until Darwin’s return in 1836. The shrub Acacia bynoeana and Bynoe Island in Australia were named after him.

Darwin frequently fell ill with seasickness, fever, exhaustion, recurring abdominal symptoms, and a leg abscess; Bynoe treated him with the limited medications then available. In his journals, he described Bynoe as “a most kind-hearted man and an excellent companion.” Writing to FitzRoy he reported: “I shall always remember with gratitude the care of Bynoe during my illness in Valparaiso” (Darwin Correspondence Project, Letter 223, 1834).

Illnesses during the Beagle voyage3

Seasickness

One of the earliest and most consistent symptoms that Darwin records is severe seasickness.4 From the outset in the Bay of Biscay and during years at sea, he wrote, “The misery I endured from seasickness is far beyond what I ever guessed at. If it were not for sea-sickness, the whole world would be sailors,” (Beagle Diary, 24 Dec 1831). In December 1835, he wrote to his sister Caroline: “There is no more Geology, but plenty of sea-sickness; hitherto the pleasures & pains have balanced each other; of the latter there is yet an abundance.” Darwin observed that lying flat in his hammock was his only relief, biscuits and raisins his only tolerated food. It continued intermittently throughout the voyage.4

Fevers and tropical infections

Darwin records various febrile episodes during the voyage. For example (Beagle Diary, 7–12 October 1833) in Bahia: “A violent headache, sickness, and shivering came on, which continued the greater part of the night. I could scarcely crawl the next morning…Mr. Bynoe gave me calomel and opium. I was not able to leave my hammock for three days.”

In Macaé (Brazil) and in Santa Fe (Argentina) he suffered bouts of fever and debility.5 In Valparaiso, Chile: “I was confined to my hammock for nearly a week by a violent fever; Bynoe attended me with his usual kindness.” (Beagle Diary, July 1834). This episode has been interpreted as typhoid fever.

The nature of these febrile illnesses is, however, speculative; they have been variously attributed to malaria, typhoid, or other tropical fevers. There is no mention in his extensive journal notes of the prescription of quinine from cinchona bark, which was available and a well known anti-malarial.6 The Beagle carried quinine, cinchona, opiates, emetics, and antiseptics, which no doubt Bynoe would have prescribed symptomatically. The crew were spared from scurvy by a diet containing pickles, dried apples, and lemon juice.

Darwin also probably suffered from altitude sickness in the Andes near Santiago. The Beagle Diary, 22 March 1835 records: “The ascent was steep and fatiguing. I was affected by shortness of breath and faintness to a degree which quite astonished me…I was compelled to lie down every few minutes; the rarefied air seemed to exhaust my strength completely.”

Gastrointestinal and abdominal complaints

In his many letters he records episodes of “stomach disorders,” loss of appetite, and exhaustion. In Valparaiso, Chile, he related, “I have been for some days unwell with a very severe headache and sickness. The Captain has delayed our sailing for my sake.”9 He wrote to his sister Caroline of this episode: “I believe the illness was caused by eating some bad food at an inn.”

In addition to his seasickness, while in Patagonia he related: “My stomach much deranged, and I feel weak and languid.” (Letter to Henslow, Nov 1833). Even on his journey home in 1836 he complained of persistent abdominal symptoms: “My stomach continues very weak; I dread the return voyage” (Diary, June 1836). During the famous British Association debate at Oxford in 18607 between Bishop Samuel Wilberforce and Thomas Huxley (nicknamed “Darwin’s bulldog”), many expected Darwin to defend his newly published doctrine; he was absent, instead confined to a hydropathic establishment in Richmond, Surrey, his stomach having “utterly broken down,” as he wrote to Charles Lyell on 25 June 1860.

An example of the of vehemence of the debate:

“If I may be allowed to inquire,” said the Bishop of Oxford, “would you rather have had an ape for your grandfather or grandmother?” “I would rather have had apes on both sides for my ancestors,” replied the naturalist, “than human beings so warped by prejudice that they were afraid to behold the truth.”8

Wound infection

In Bahia in Brazil in March 1832, he developed an infection of his leg. Darwin wrote: “I pricked my knee some days since, & it is now so much swollen that I am unable to walk.” There is no record of an abscess being drained by Bynoe in Darwin’s diary5 or in later biographies, only that he was confined to bed.

Nervous symptoms

There were at times arguments with FitzRoy, a deeply religious aristocrat and meteorologist of distinction,† but renowned for his fiery temper. In the Darwin diaries9 are letters from the voyage, which plainly show a sensitive and self-critical man, who in addition to his physical illnesses was prone to anxiety, fatigue, languor, and homesickness.

Years later, writing to Thomas Rivers, a nurseryman, he stated:

I suffer severely from ill-health of a very peculiar kind, which prevents me from all mental excitement, which is always followed by spasmotic sickness, and I do not think I could stand conversation with you, which to me would be so full of enjoyment. (Darwin Correspondence Project, 1862;10(635))10

What is clear is that the illnesses during the voyage, especially the severe episodes of debilitating languor, fatigue, and gastrointestinal symptoms, were later mirrored in the pattern of his life-long health problems.11 Back at Down House, Darwin continued to suffer from intermittent vomiting, flatulence, fatigue and inertia, eczema, boils, and palpitations, whose origin has been much debated. Speculations have included psychosomatic illness, Chagas’ disease, Lyme disease, lactose intolerance, and cyclical vomiting syndrome. However, as with all his illnesses, there is a dearth of clinical detail so that the possible causes are mere guesswork. He tried hydrotherapy, various diets, and antacids of chalk and magnesia, with limited success.

His symptoms fortunately did not prevent his continuing important biological research and writing. Nor did they stop his fathering ten children. When well, he frequently took walks, enjoyed swimming, and traveled to attend numerous meetings of the Geological Society of London and the Royal Society, as well as often visiting his native Shrewsbury and many friends and colleagues throughout Britain.6 He continued to experiment and to write at Down House where he lived with his wife Emma and their family from 1842 until his death in 1882.

Five years after his death, his son Francis Darwin published The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin in three volumes, which disclosed his massive output of letters. His correspondents included amongst many others: Alfred Russel Wallace, Thomas Henry Huxley, Francis Galton, Adam Sedgwick, John Stevens Henslow, Joseph Dalton Hooker, Asa Gray, Ernst Haeckel, George Eliot, and Charles Kingsley.

From Down House he wrote his major works:

- The Voyage of the Beagle, originally published as Journal and Remarks (1839)

- The Structure and Distribution of Coral Reefs (1842)

- Geological Observations on Volcanic Islands (1844)

- Geological Observations on South America (1846)

- On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1859)

- On the Various Contrivances by which British and Foreign Orchids are Fertilised by Insects (1862)

- The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication (1868)

- The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871)

- The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872)

- Insectivorous Plants (1875)

- The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species (1877)

- The Formation of Vegetable Mould through the Action of Worms (1881)

Darwin died aged seventy-three at Down House on 19 April 1882 with symptoms suggestive of ischemic heart disease.10 He was buried in Westminster Abbey, an honor seldom accorded to any man whose theories had stirred so much controversy. His wife Emma (née Wedgwood) died in 1896. Seven of their ten children survived childhood.

End notes

- * No attempt is made here to retell Darwin’s observations and conclusions about evolution, nor their highly contentious implications for orthodox religious beliefs of the period, which were spectacularly debated by Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford, and Thomas Henry Huxley at the British Association meeting on 30 June 1860 at the Oxford University Museum.

- † In 1863, FitzRoy published Weather Book, where he stated that Darwinian evolution was incompatible with Christian biblical doctrine.

References

- John van Wyhe, ed. The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. 2002. http://darwin-online.org.uk/

- Keynes RD. The Beagle Record: Selections from the Original Pictorial Records and Written Accounts of the Voyage of HMS Beagle. Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Hayman J. Darwin’s illness during the Beagle voyage. Medical Journal of Australia 2009:191.

- Darwin Charles. The Beagle Diary of Charles Darwin (ed. Nora Barlow, Cambridge Univ. Press, 1933). Darwin Online, Darwin’s Beagle Diary and related materials: www.darwin-online.org.uk

- Darwin Correspondence Project, Vol. 1, letters to Henslow, 1834–1835.

- Darwin Online, Darwin’s Beagle Diary and related materials: www.darwin-online.org.uk

- British Association debate. Darwin Correspondence Project. https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/commentary/religion/british-association-meeting-1860

- Reading Mercury, 7 July 1860, p. 10. Cited by: England R. Censoring Huxley and Wilberforce: A new source for the meeting that the Athenaeum ‘wisely softened down’. Notes Rec R Soc Lond. 2017 Dec 20;71(4):371-384.

- Keynes RD (Ed.) Charles Darwin’s Beagle Diary. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Hayman JA. Darwin’s illness revisited. British Medical Journal 2009;339:b4968.

- Desmond A, Moore JR. Darwin. London: Penguin, 1992.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.