Mikaela Melnychuk

Juhi Patel

Noel Brownlee

Blacksburg, Virginia

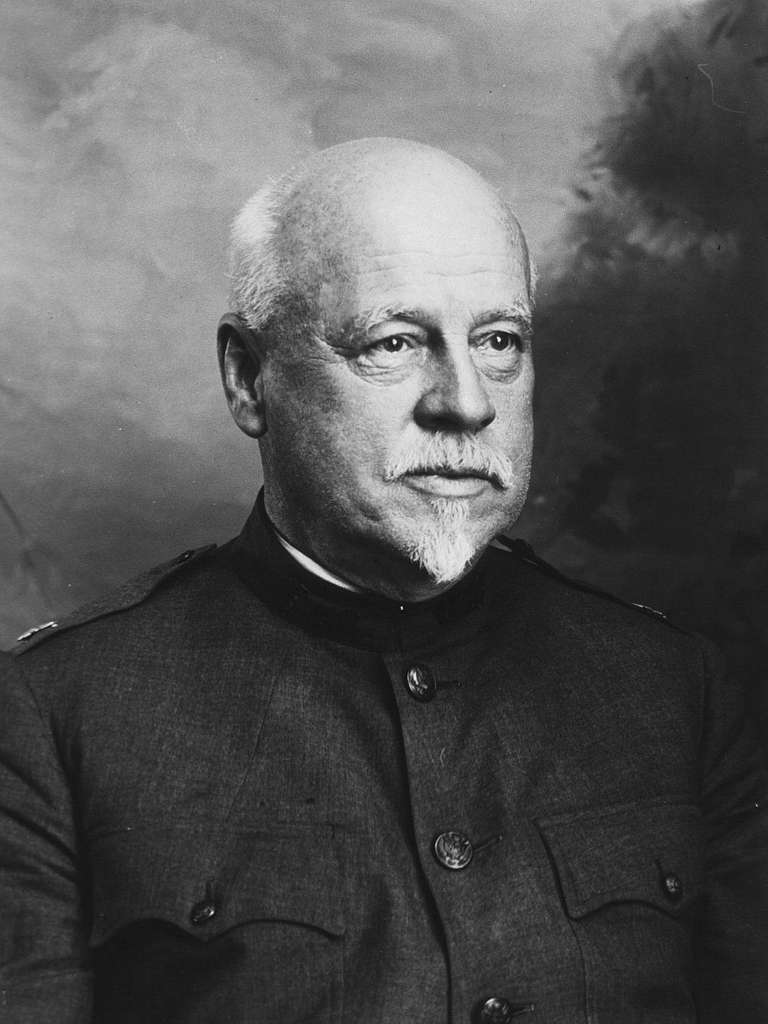

William H. Welch was an American physician renowned for his work in pathology, public health, bacteriology, and as the “father of American medical education.”1,2 He was part of the “Big Four” founding professors at Johns Hopkins Hospital and was the first dean at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.2

Welch was born on April 8, 1850, in Norfolk, Connecticut. His mother died when he was six months old, and his grandmother raised him while his father, a beloved physician, cared for the local community. Welch enrolled at Yale College in 1866; however, he was not initially interested in pursuing medicine. After returning home from teaching at a failed institution, his family encouraged him to follow in his father’s footsteps. In 1872, he entered the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York. This is when Welch experienced the lacking American medical education system, describing his single medical exam at the end of three years as “the easiest … I ever entered since leaving boarding school.”3,4 Yet in the anatomy laboratory, he discovered an enduring fascination with pathological anatomy. After graduating in 1875, he interned in pathology, which was in its early beginnings as a discipline, at Bellevue Hospital in New York.4

American medicine in the late 1800s focused on clinical practice, lagging behind the laboratory-driven practices of Europe.5 Ambitious and unimpressed with the quality of education available to him in the US, Welch’s ambitions took him abroad to Europe, where many physicians studied in Germany and Austria for their renowned medical research.4 Simon Flexner described the results of Welch’s study there as being “perhaps the most important ever taken by an American doctor.”6 After being denied at Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen’s laboratory for knowing “too little,” he studied at universities where he experienced the European model of applied sciences in medical education.4,7 One of his most important interactions was with John Shaw Billings, who was entrusted with selecting faculty for Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. After spending two years learning under notable physicians such as Carl Ludwig, Welch returned to the US to integrate laboratory medicine into American medical education.3

When he returned to New York, Welch was offered an unpaid pathology lecturer position at his alma mater; however, he was uninterested because they could not provide him with a room to start a laboratory. In 1879, he returned to Bellevue Medical College, where he established his laboratory and research. Starting his laboratory came with many obstacles. Bellevue offered him three rooms with tables and $25 for equipment. As a testament to his dedication to the implementation of laboratory science in medical education, Welch gathered antique microscopes and collected frogs himself for teaching his students.3,4 He was known for “leak[ing] knowledge” and his dedication to answering any questions from his students.6 Word of his course spread, and students from other New York medical schools began enrolling in his class to have this unique experience.3,4

Just after Welch graduated from medical school, the first American research university, Johns Hopkins, opened in Baltimore, Maryland.8 Billings officially interviewed Welch in 1884, and thought that Welch was “the best man in this country for the Hopkins.”3 At the age of thirty-three, Welch accepted the first faculty and dean position at Johns Hopkins University and its School of Medicine.4 Before moving to Baltimore, Daniel Gilman, the university’s president, offered him the opportunity to return to Europe for further education. He toured medical laboratories led by revolutionary scientists, including Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur.3 He returned with deeper knowledge of bacteriology, later identifying the organism responsible for gas gangrene, Clostridium perfringens (formerly known as C. welchii), but also with a conviction that American medical schools could match Europe’s if grounded in laboratory science and rigorous education.4

Welch cultivated “a general spirit of research” in his pathology laboratory at Johns Hopkins. He was welcoming to all students regardless of religion, gender, or prior experience. He helped students who were interested in research and education by providing opportunities and an atmosphere to “come not from those who make utility their guiding principle, but from the investigators of truth for its own sake.”4 While Welch may not have had many personal scientific breakthroughs, his influence inspired his students’ curiosity. Some of his students who contributed greatly to medicine and research include Simon Flexner, Walter Reed, James Carroll, and Jesse Lazear.2,6 Though Welch’s pathology laboratory was unique, it was not the only difference that made Johns Hopkins stand out.

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine was the first of its kind in America. Before its establishment, American medical school admissions were primarily based on the ability to pay tuition. In most instances, students were not required to have higher education.9 With Welch’s influence, Johns Hopkins was the first medical school to require a bachelor’s degree with a focus in natural sciences, along with the ability to read Latin and sight-read French or German.10,11 The medical school was closely associated with Johns Hopkins Hospital, which bolstered students’ clinical experience well above the contemporary baseline.5 In addition to Welch, the other “Big Four” founding professors included internist William Osler, surgeon William Stewart Halsted, and gynecological surgeon Howard Kelly.2 These four physicians set a standard in American medical education that would have a ripple effect.

The success of Johns Hopkins slowly drew attention. Over the next decade, some medical schools began to raise their admissions standards. Still, there were no uniform guidelines for medical education, and most institutions remained focused on profit rather than on producing well-trained physicians.3,4 This model changed in 1910 when Abraham Flexner published Medical Education in the United States and Canada, commonly known as “The Flexner Report.”12 Flexner examined the medical education system through a critical lens. He was dissatisfied with inadequacies in laboratory practice, administration, and standard curriculum. Very few schools met his standards; however, he was pleased with how Johns Hopkins Medical School operated, specifically with Welch’s contributions, stating that if he (Flexner) was given one million dollars for medical education, he would “give it to Dr. Welch.”4 He used the school as a paradigm and recommended stricter medical education standards that still have an effect today.12

Decades after helping to found Johns Hopkins and transforming American medical education, Welch was presented with another opportunity that aligned with his passions: creating the first school of public health in the US. The Rockefeller Foundation chose Johns Hopkins to open the School of Hygiene and Public Health in 1916.9 Welch, along with Wickliffe Rose, known for a public health campaign to eradicate hookworm in the Southern US, was chosen to help lay the foundation of the school. Rose emphasized the clinical practice of clinical health, while Welch favored research.13,14 Welch resigned from being a professor at the medical school to take the position as the first Dean of the School of Public Health. Two years later, Welch would aid in addressing one of the world’s major public health threats, the Great Influenza.6

In the fall of 1918, Welch was summoned to Camp Devens to consult on a fatal illness spreading through the United States military.4 He was “worried and disturbed” after witnessing an autopsy of a recently deceased patient and said, “This must be some new kind of infection or plague.”15 He quickly made three telephone calls to help combat further spread of infection and death, which resulted in autopsies being performed to understand the pathology of the infection. Research led to the conclusion that this new infection was caused by a virus, and camp hospitals were expanded for the impending influx of patients.4,15 Without Welch’s quick actions, it is likely that many more lives would have been lost.

Welch died at the age of eighty-four from prostatic adenocarcinoma. Ironically, someone who was initially hesitant about pursuing a career in medicine became one of the most influential people in American medicine. He received many awards during and after his lifetime, and has a Johns Hopkins library named in his honor.11 Though Welch strived for innovative research, he also saw the importance of studying the past, stating that “the study of the historical and cultural background of medicine and the natural sciences through the ages … helps make better teachers and better doctors.”16 It is fitting that in 1950, the American Association for the History of Medicine created an annual award named the “William H. Welch Medal” for authors of outstanding medical history books.17 Without a doubt, William H. Welch changed the course of medicine not only in the United States, but across the world.

References

- “Physicians Honor Dr. W.H. Welch Here.” The New York Times, April 5, 1930, sec. R.

- “The Founding Physicians.” Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed June 1, 2025. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/about/history/history-of-jhh/founding-physicians.

- Silverman, Barry D. “William Henry Welch (1850–1934): The Road to Johns Hopkins.” Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 24, no. 3 (July 2011): 236–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2011.11928722.

- Hruban, Ralph H, and Will Linder. “William Henry Welch.” Essay. In A Scientific Revolution: Ten Men and Women Who Reinvented American Medicine, 41–61. Pegasus, 2022.

- Turner, Edward Lewis, and Harold Scarborough. “Medical Education.” Encyclopædia Britannica, April 9, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/science/medical-education.

- Barry, John H. “Part I: The Warriors.” Essay. In The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History, 36–87. New York, New York: Penguin Books, 2005.

- Turner, Edward Lewis, and Alan Gregg. “Modern Patterns of Medical Education.” Encyclopædia Britannica, April 9, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/science/medical-education/Modern-patterns-of-medical-education.

- Pant, Anoushka. “Johns Hopkins University.” Encyclopædia Britannica, May 29, 2025. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Johns-Hopkins-University.

- Iacobelli, Teresa. “Early 20th Century Reforms of Medical Education Worldwide.” RE:source, January 10, 2022. https://resource.rockarch.org/story/early-20th-century-reforms-of-medical-education-worldwide/.

- “Medical Education, Course of Study.” Essay. In Medical School, n.d.

- Flexner, Simon. “Biographical Memoir of William Henry Welch.” National Academy of Sciences, 1942. https://www.nasonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/welch-william.pdf.

- Flexner, Abraham. Medical Education in the United States and Canada: A Report to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. New York: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 1910.

- “Wickliffe Rose.” DIMES. Accessed June 1, 2025. https://dimes.rockarch.org/agents/S29da4c4LZop2Y2s3HunTx.

- Fee, Elizabeth. “The Founding of Schools of Public Health.” Essay. In Who Will Keep the Public Healthy?: Educating Public Health Professionals for the 21st Century, 222–31. Washington, District of Columbia: National Academies Press, 2003.

- Podolsky, Scott. “‘Some New Kind of Infection or Plague:’ The 1918 Flu Pandemic & Covid-19.” May 14, 2020. https://info.primarycare.hms.harvard.edu/perspectives/articles/1918-influenza-and-covid19.

- Welch, William H. “Reminiscences of the Early Days of the Medical School.” YouTube, May 13, 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=emGPMVfad1M.

- “William H. Welch Medal.” American Association for the History of Medicine. Accessed June 1, 2025. https://histmed.org/william-h-welch-medal/.

- “William H. Welch.” NIH National Library of Medicine: 101431676, http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101431676.

MIKAELA MELNYCHUK earned her BS in chemistry from the University of North Georgia in 2017. She is currently a fourth-year medical student pursuing her doctorate in osteopathic medicine at VCOM.

JUHI PATEL earned her BS in microbiology and classics from the University of Tennessee in 2019 and her MA in History of Medicine from Newcastle University in 2020. She is currently a fourth-year medical student pursuing her doctorate in osteopathic medicine at VCOM.

DR. NOEL BROWNLEE earned his PhD in cancer biology at the Medical University of South Carolina and his MD from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine, followed by graduate medical education in anatomic and clinical pathology at Duke, Wake Forest, and Johns Hopkins. He is currently Professor and Chair of Pathology at VCOM.