Saty Satya-Murti

Santa Maria, California, United States

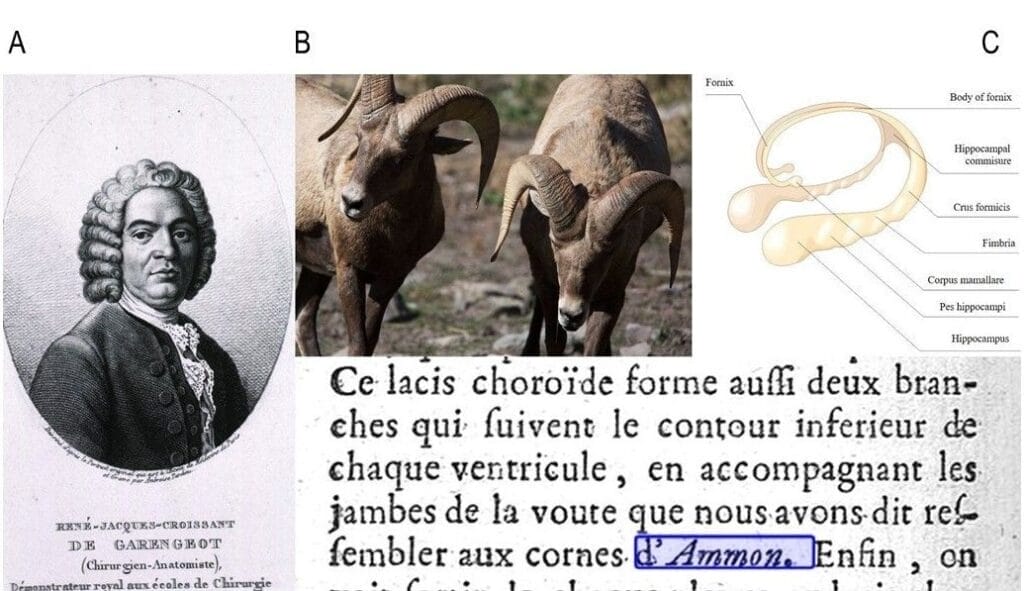

B. Typical curved horns of rams. US Fish & Wildlife Service.

C. Human Ammon’s horn with hippocampus. Graphic by Hariadhi on Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Bottom text: Garengeot’s 1728 description, probably the earliest, of human Ammon’s Horn. From Splanchnologie ou l’anatomie des viscères 1728, p. 468. Internet Archive.

In the transitional decades from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, restrictions against human cadaveric dissection gradually dissipated. This gave Italian and French anatomists an opportunity to break away from rigid dogmas and incorrect Galenic (Galen of Pergamon, 129–216 CE) pronouncements. Religious and moral taboos had long prohibited detailed human dissections,1,2 and Galenic teachings were considered sacred and beyond dispute. However, his descriptions of human anatomy were based on generous extrapolations and analogies drawn from animal dissections, rather than direct observation of human anatomy.3 Obeisance to Galen led to many errors that persisted for centuries.

Animal anatomy is not human anatomy

Two such errors, the rete mirabile and Galenic isomorphism, deserve special mention.4 Galen maintained that animals, including mammals such as humans, have a complex network of arteriovenous connections intracranially or just outside the cranium. Unfamiliar with human anatomy, Galen claimed that this “wonderful net” (rete mirabile) maintained circulatory exchange in the human brain. Regardless of the grave follies of extrapolation from animals to humans, no one contradicted Galen until the 1500s. William Harvey (1578–1657) and Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), alumni of the new school in Padua, posed the earliest redoubtable opposition to Galen’s ideas. They and other European Renaissance-Enlightenment anatomists, relying on direct observation and empiricism, raised strong objections to Galenic teachings.

In the second example, Galenic isomorphism posited that the female body is structured by nature to mimic and contain exact counterparts to male organs. In this system, the ovaries were actually female testicles juxtaposed to the uterus, and the vagina an analogue of the penis. It was considered risqué to acknowledge that female anatomy was not a duplication of male anatomy. Such expositions were considered “an affront [to] ‘Decorum’” in sixteenth-century medical writings.5

Early dissectionists Jacobus Sylvius (1478–1555) and Andreas Vesalius studied human and animal anatomy with a focus on meticulous direct observation and deduction. The prevailing creed at the time was that if anyone, Vesalius included, found human cadaveric structures that differed from Galen’s animal-based anatomy, then “the fault lay not with Galen, but with the corpse.”6

However, Vesalius’ human dissections clearly demonstrated the absence of rete mirabile in humans. His daring and successful counterdemonstration against Galenic centuries-old anatomical teaching energized and sharpened the skills of subsequent empirical anatomists. They found human anatomical arrangements were often, but not always, morphologically different from animals. Because they also found mimicry in the shapes and configurations of human anatomy with what they observed among animals, plants, and nature, they borrowed and analogized concepts and terms and applied them to human architecture. Once established as a respectable observation-based science, the subsequent arrival of microscopic observations spawned more anatomical descriptions. Such mimetic medical terminologies flourished from the 1500s onwards. This irrepressible cognitive urge to analogize is recognizable even today in microscopic, molecular, and radiological imaging.7,8

Rams, goats, and sea monsters

Of many animal analogies, rams and goats have an enduring legacy. The Ammon’s horn in the brain and the tragus of the ear are two examples. Adult ram’s horns form an impressive curve with a ridged, broad base and a sweeping C-shaped taper. Ammon (or Amun) was an ancient Egyptian god of power, protection, and virility who was frequently portrayed with ram’s horns. While dissecting the human brain, French anatomist René-Jacques-Croissant De Garengeot (1688–1759) was impressed by the choroid plexus and the nearby C-shaped, tapering, bilateral deep brain structure arising from the temporal horns (the hippocampus) curved around the callosum to end in the fornix and mamillary bodies. On finding this structure, he wrote:

This choroid plexus also forms two branches that follow the lower contour of each ventricle, accompanying the legs of the vault that we have said resemble the horns of Ammon.3,9 (Figure 1)

He went on to label his newfound structure as Ammon’s horn (cornu Ammonis), a term that has gained regular mention in scientific literature for three centuries.3,9,10

The hippocampus, a part of Ammon’s horn, is a neural structure in the medial temporal lobe. It has a distinctive curve and shape that has a striking resemblance to the seahorse (hippocampus) or sea monster in Greek mythology.3,10 (Figure 2) The credit for likening the human hippocampus to the Greek mythological seahorse goes to a Venetian anatomist, Julius Caesar Aranzi (1529–1589).

The etymon for the tragus of the ear traces its droll origin to physician-anatomist Helkiah Crooke (1576–1648). He named the triangular cartilage anterior to the external auditory meatus as “tragus” (τράγος in Greek). Tragos, in Greek, is a goat, and the hair growing near the meatus in older men was thought to bear a resemblance to a male goat’s chin.

Horns and wings

Bottom: Sphenoid bone plate with its wings. Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica (Liber I), 1543, p. 25. US National Library of Medicine.

Whenever anatomists recognized the presence of bilateral, smaller extensions arising from major midline organs, they often labeled them as horns. Jacques Guillemeau (1550–1613), a pioneering French obstetrician, ophthalmologist, and surgeon to French royalty, had commented on the uterus having horns (cornu uteri). In passing, he labeled the ovaries as “The Testicles or Hornes of the Wombe” in 1598. This is an example of Galenic isomorphism, which taught that female anatomy is but a replica of the male.5,11 Horns persist in modern anatomical descriptions, such as the anterior (frontal), posterior (occipital), and inferior (temporal) horns of the cerebral ventricles. The hyoid bone has greater and lesser horns; the spinal cord has its anterior and posterior horns. Renal calculi take on a staghorn shape sometimes.

Flattened lateral extensions became wings, not horns. The shape and beauty of the unfolded wings (ala) of birds in flight drew comparisons to midline bones with side plates. Andreas Vesalius, in his 1543 book De Humani Corporis Fabrica, identified the lateral plates of the sphenoid bone as its wings. (Figure 3) The terms greater and lesser sphenoid wings are still in use today. Equally familiar are the sacral and iliac alae of the pelvis.

Several other anatomical structures and diagnostic nomenclatures have links to animal names because of their morphological verisimilitude. For instance, pathologists speak of an “owl’s eye” microscopic appearance of infected cells with their intranuclear cytomegalovirus inclusions. Other examples are cauda equina (horse tail), leonine facies, elephantiasis, lupus (wolf) erythematosus (facial appearance resembling a wolf bite), cochlea (common snail), and the raccoon eyes of periorbital ecchymosis.

From dissection theaters to imaging suites and genes

In recent times, the novelty of naming anatomical findings has moved away from dissection rooms to the domain of radiology, imaging, and molecular biology. Of historic significance is the “Scottie dog” sign. Before the advent of CT and MRI, this sign on X-ray was helpful in diagnosing spondylolysis because an oblique view of the pars interarticularis defect of the lumbar spine took on the profile of a Scottish terrier with a collar around its neck.12 A recent imaging example is the MRI-based appearance of the “owl’s eyes” or “snake eyes” sign. This imaging feature shows the presence ofbilaterally symmetrical circumscribed bright circular spots of increased signal intensity in the central spinal cord, indicative of intramedullary gliosis. It is noted in multiple conditions including spinal cord infarction. The “hummingbird sign” of brainstem atrophy due to progressive supranuclear palsy is another relatively convincing imaging abnormality. Many other comparisons to animal morphologies, frequent in CT or MRI parlance, however, may stress the imagination of non-radiologists. A listing of such images is available.13

Genetics is also a rich source of naming conventions that relate to animals. The family of “hedgehog” genes were so named because mutations were found to cause spiky projections on the larvae of fruit flies.14 “Sonic hedgehog” is a vital gene whose protein product is essential for embryonic development.14,15 It is named after 1990s video game character Sonic the Hedgehog, a blue anthropomorphic hedgehog with superspeed. Several developmental disorders such as holoprosencephaly are attributable to this gene malfunction. Another is the NOTCH 1 gene. Its mutation causes indentations, or notches, on the wings of fruit flies. Human NOTCH gene mutations also produce developmental disorders in humans.16

There is a strong human tendency to link apparently unlike entities because of physical resemblance or functional commonality. Analogies connect perceived novelties (the new target) to established constructions (known sources). We tend to perceive what is new in terms of what we know and have seen already. This process aids in understanding, promotes creativity, and fosters communication.17 From antiquity to current times, this process of creating anthropic analogies has taken varying forms across scientific fields, including medicine and healthcare, and continues to provide us with rich mnemonic vocabulary and creative repertoire.

References

- Ghosh SK. Human cadaveric dissection: A historical account from ancient Greece to the modern era. Anat Cell Biol. 2015;48(3):153-169. doi:10.5115/acb.2015.48.3.153

- Pretterklieber ML. Nomina anatomica-unde venient et quo vaditis? Anat Sci Int. 2024;99(4):333-347. doi:10.1007/s12565-024-00762-w

- Iniesta I. On the origin of Ammon’s horn. Neurología (English Edition). 2014;29(8):490-496. doi:10.1016/j.nrleng.2012.03.024

- Lanska DJ. Evolution of the myth of the human rete mirabile traced through text and illustrations in printed books: The case of Vesalius and his plagiarists. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 2022;31(2-3):221-261. doi:10.1080/0964704X.2021.2024406

- Richards J. Reading and Hearing The Womans Booke in Early Modern England. bhm. 2015;89(3):434-462. doi:10.1353/bhm.2015.0081

- 6. Porter R. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. W.W. Norton & Company; 1999, p. 171.

- Maryenko N. “Arbor Vitae Cerebelli: Fractal Properties and Their Quantitative Assessment by Novel ‘Contour Scaling’ Fractal Analysis Method (an Anatomical Study).” Translational Research in Anatomy 37 (November 1, 2024): 100352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tria.2024.100352.

- Satya-Murti S. Mimetic medical terminologies inspired by the plant world. Hektoen International, Winter 2025. https://hekint.org/2025/02/03/mimetic-medical-terminologies-inspired-by-the-plant-world/

- de Garengeot RJC. Splanchnologie ou l’anatomie des viscères. Paris, G. Cavellier; 1728. Accessed March 10, 2025. http://archive.org/details/BIUSante_31858

- 10. Pearce JMS. Ammon’s horn and the hippocampus. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2001;71(3):351. doi:10.1136/jnnp.71.3.351.

- Oxford English Dictionary. Horn, noun: Meaning and use. s.v. Jacques Guillemeau. The Frenche chirurgerye; or, All the manualle operations of chirurgerye, 1st edition, 1598. Trans. A.M. https://www.oed.com/dictionary/horn_n?tab=meaning_and_use#1267768

- Baig M, Byrne F, Devitt A, McCabe JP. Signs of Nature in Spine Radiology. Cureus. Published online April 10, 2018. doi:10.7759/cureus.2456

- Animal and animal produce inspired signs. Radiopedia. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/animal-and-animal-produce-inspired-signs?lang=us radiopedia

- Feng R, Xiao C, Zavros Y. The Role of Sonic Hedgehog as a Regulator of Gastric Function and Differentiation. Vitam Horm 2012; 88:473-489. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-394622-5.00021-3.

- National Library of Medicine. SHH gene sonic hedgehog signaling molecule. MedlinePlus, https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/shh/. Accessed August 28, 2025.

- NOTCH Receptor I. OMIM® An Online Catalog of Human Genes and Genetic Disorders – Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man®. https://www.omim.org/ Accessed August 28, 2025.

- Pena GP, De Souza Andrade-Filho J. Analogies in medicine: valuable for learning, reasoning, remembering and naming. Adv in Health Sci Educ. 2010;15(4):609-619. doi:10.1007/s10459-008-9126-2

SATY SATYA-MURTI, MD, FAAN, is a clinical neurologist and health policy consultant. Following retirement, he has spent time researching cognitive biases, the social underpinnings of clinical medicine, Progressive Era medicine, and forensic sciences. He enjoys grandparenting, solar cooking, and volunteering.