Henri Colt

Irvine, California, United States

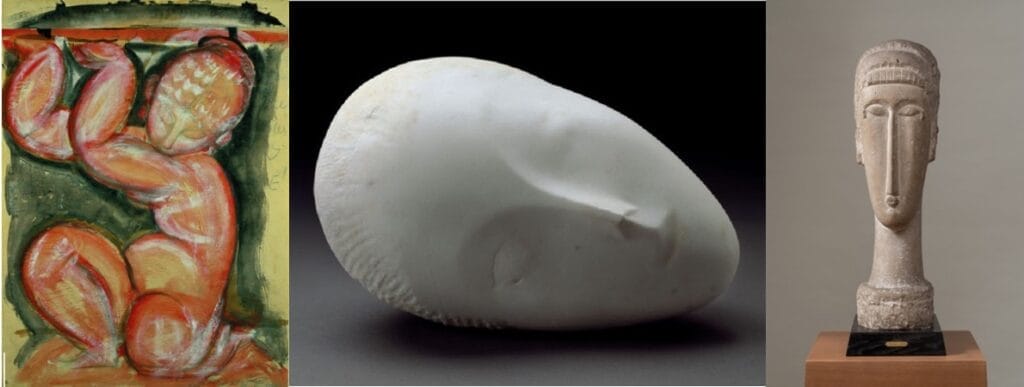

b. Brancusi Sleeping Muse, I. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington D.C.

Photo by Tabbycatlove on Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0.

c. Modigliani Head. 1911/1912. Barnes Foundation Collection, accession #249.

In late 1908, a Parisian dermatologist named Paul Alexandre introduced a struggling twenty-four-year-old Jewish-Italian artist named Amedeo Modigliani to a friend with whom the young Italian would soon develop a close relationship, the Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi (1867–1957). Brancusi found Modigliani a studio close to his own at 14 Cité Falguière, on a small cul-de-sac between the large artist residence La Ruche and the Boulevard Raspail in the increasingly hip neighborhood of Montparnasse. Amedeo occupied this studio for several years, during which he painted less and committed himself instead to carving directly on limestone blocks, many of which he obtained from nearby construction sites.1

Inspired by Cycladic, Egyptian, Khmer, and African tribal art seen during his trips to the Louvre and Trocadéro Museums, Amedeo first embarked on an obsessive quest to architecturally reduce empty space on his drawing paper. Leaving aside his sketches of theater scenes, circus performers, and female nudes, he began drawing women, hermaphrodites, and figures with androgynous features in various austere and geometric positions. Their faces had elegant, elongated forms, expressionless or absent eyes, and long, narrow noses. Drawn in profile, many resembled figures found in the hieroglyphics of ancient Egypt or portrayed in African tribal art, including Baule masks from the Ivory Coast. Some of these he called caryatides, from the Greek word for a woman of Caryae; partly draped figures, usually crouching or standing, that were carved into marble on monuments or holding up roofs of ancient Greek temples, inspired by archaic art during the Cycladic period (2800–2300 BC). The Russian/French sculptor, Ossip Zadkine, recalled seeing some of these masterpieces that were far more than preparatory sketches for Modigliani’s subsequent stone carvings: “I was going to see these large drawings of caryatids,” he said, “in which shapes, children’s bodies were barely supporting the weight of a heavy blue Italian sky.”2

In many of Modigliani’s drawings and ensuing sculptures, the artist incorporated the archaic smile used by Greek sculptors of the sixth century BC to display a sense of repose and gentle well-being. In others, a full upper and lower lip smile is reminiscent of the Khmer smile of hundreds of stone apsaras—celestial dancer statues of the Angkor dynasty in Cambodia, between the ninth and fifteenth century AD. Portuguese sculptor Diogo de Macedo said that “his sculptures really looked like exotic Jain divinities, mysterious and sophisticated.”3 Brancusi’s influence is evident, especially when comparing Modigliani’s series of “Têtes” with Brancusi’s display of exquisite ovoid heads, such as Sleeping Muse, a bronze sculpture of a sleeping head lying on its side with its eyes closed, initially done in marble in 1909.4

Suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis, which Modigliani had contracted as a child, the Italian may have had difficulty working with stone. Less than thirty authentic sculptures are in existence. Dust and debris from sculpting can certainly exacerbate a cough, and continuously wielding heavy tools is tedious and tiresome for anyone in a weakened physical condition. (Amedeo died at the age of thirty-five, presumably from tuberculous meningitis). Although he left no diary and very few notes about his artistic journey, it seems that by 1914, the talented artist had abandoned sculpture altogether and dedicated himself solely to perfecting a distinctive form of portraiture that made him one of the most copied painters in history. His portraits of women with their sensitive features and long swan-like necks, with heads drooping like flowers on their stems, are instantly recognizable. Although Amedeo’s work spanned less than fifteen years (he died January 24, 1920), his paintings are also among the most prized among collectors today. In 2018, a Modigliani “Great nude” was sold at Sotheby’s for a record $157.2 million.5

Regarding Modigliani’s sculptures, few survive.6 Almost all were carved in sandstone or limestone, which is softer and more forgiving than marble. They range in height from twenty-four to sixty-three inches. A few are non-finito and remain unpolished, but some seem more finished than others. Many are elongated “Heads” with androgynous features and minimal facial structures.7 Their long necks and oval-shaped faces have rounded chins and usually straight, arrow-like noses that exaggerate their verticality and occupy a central balancing position in the carvings. Some have closed lips as in a puckered kiss. At night, Amedeo placed candles around them. According to his art dealer, Paul Guillaume, “Modi dreamed of leaving to humanity a temple he had built from his own plans. He was not thinking of a temple to honor God, but of one to honor Humanity.”8

References

- Hochart, C., Genty-Vincent, A., Coquinot, Y., & Menu, M. (2022). Étude des traces d’outils et des pierres de trois sculptures de Modigliani. In Les Secrets de Modigliani: Techniques et pratiques artistiques d’Amedeo Modigliani (pp. 125-135). Éditions invenit, Lille.

- Zadkine, O. (1930). Souvenirs. Paris, Montparnasse, (p. 12).

- Colt H. (2024). Becoming Modigliani (p. 117). Rake Press, Laguna Beach, CA.

- Brancusi, C. (n.d.). La Baronne R.F. Retrieved from https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en/ressources/oeuvre/cpjb5k.

- Sotheby’s. (2018). At $157.2 Million, Modigliani’s Greatest Nude Is Also the Most Expensive Painting Ever Sold at Sotheby’s. https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/at-157-2-million-modiglianis-greatest-nude-is-also-the-most-expensive-painting-ever-sold-at-sothebys

- Ceroni, A. (1965). Amedeo Modigliani: Dessins et Sculptures. Edizioni Del Milione, Milan.

- Buckley, B., Fraquelli, S., Ireson, M., & King, A. (Eds.). (2022). Modigliani Up Close: Carving a niche. The Barnes Foundation (pp. 108, 89-122). Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Werner, A. (1985). Modigliani. Harry N. Abrams, New York.

HENRI COLT is an emeritus professor of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the University of California, Irvine. He is a philosophical practitioner and mountaineer who loves beauty in all its forms. In addition to scientific medical writings, he is the author of 30 Stories About Life & Death and Becoming Modigliani, a biography about Jewish-Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani. Colt’s stories have been published in Hektoen International, Cabinet of Heed, Active Muse, and other journals.