George Christopher

Michigan, United States

Sinclair Lewis’ novel Arrowsmith (1925) is a biography of the fictional physician Martin Arrowsmith that chronicles his life from childhood through the transitions of his medical career. The novel spans the protagonist’s years in medical school and subsequent roles as a hospital house officer, clinician in solo practice, public health official, clinical pathologist in a large group practice, and researcher at an independent research institute. The novel was granted the 1926 Pulitzer Prize, but Lewis declined to receive the award. Medical details of remarkable depth and accuracy were provided by Paul de Kruif, a physician and microbiologist.

The novel reflects the reforms of medical education that followed the 1910 Flexner Report, authored by Abraham Flexner and Herman Gates Weiskotten, that critically evaluated medical educational practices in the United States and Canada. Even though the novel was published a century ago, certain items will resonate with present-day readers; these include the description of Arrowsmith’s preclinical curriculum—biochemistry, physiology, pharmacology, microbiology, and anatomy, including the “On Old Olympus Towering Top” mnemonic that many of us relied upon to memorize the cranial nerves. The story also emphasizes the value of mentorship, illustrated by the enduring relationship between Arrowsmith and his microbiology professor, Dr. Gottlieb.

Of note are descriptions of the clinical features of plague (an acute regional lymphadenitis caused by Yersinia pestis that may progress to sepsis and metastatic infection of the lungs, causing a necrotizing pulmonary infection, cough, and respiratory droplet transmission that results in secondary cases of pneumonia); the role of rats as disease reservoirs and the importance of rat extermination in outbreak control; bacteriophage (phage) therapy; and a mention of preclinical research on antibacterial chemotherapy, which later came to fruition with the introduction of sulfonamides in the 1930s and penicillin in the 1940s.

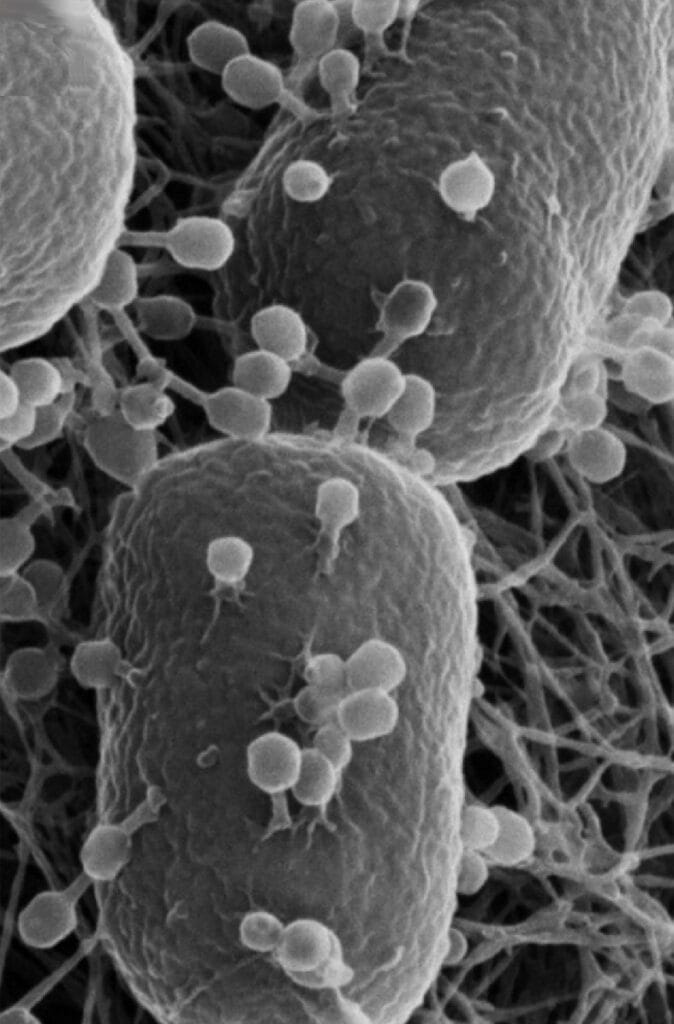

The existence of bacteriophages (viruses that infect and kill bacteria) was first suggested by the independent observations of Frederick Twort and Felix d’Herelle in 1915 and 1917, respectively, that some bacterial culture supernatants could sterilize other bacterial cultures. They ascribed the antibacterial activity to unidentified non-filterable agents (because electron microscopy had not yet been invented, viruses could not be visualized). The novel portrays Dr. Arrowsmith as engaging in phage research and correctly refers to the work of d’Herelle and the controversy as to whether the active agent was a microbe (promoted by d’Herelle) or a bacterial metabolite (“enzyme”; promoted by Twort). D’Herelle introduced phage therapy in 1919 when he treated four patients with dysentery, of whom all survived. In 1927, he utilized phage therapy in a cholera epidemic in India and reported reduced mortality among treated patients vs. those receiving supportive care alone (8% vs. 63%, respectively).

Phage therapy was adopted in Eastern Europe, where it is still practiced today. It was also used in Western Europe and the US to treat intestinal, respiratory, skin, and urinary tract infections during the 1920s into the 1940s. However, it was beset by incomplete understanding of phage biology, inconsistent skill in phage cultivation, the marketing of phage preparations with little to no phage content and poor performance, and a paucity of available clinical trial data. Phage treatments were supplanted by antibiotics but have generated renewed interest in the context of antimicrobial resistance. Phage preparations have received regulatory approvals and are in use as food additives to vegetables, fruit, cheese, and cooked meats to prevent food-borne infections and are also utilized as environmental disinfectants and in water purification. Their potential use as anti-infective therapeutics is supported by previous clinical experience, case reports, small case series, and limited clinical trial data; larger controlled clinical trials are underway to evaluate their potential roles as alternatives or adjuncts to antibiotic therapy.

The novel reaches a climax when an outbreak of plague strikes the fictitious Caribbean island of St. Hubert. Arrowsmith leads a team to test the efficacy of a phage preparation targeting Y. pestis, intending to conduct a controlled trial in locations experiencing a low plague incidence, but with an option for unrestricted access (compassionate use) in areas with high incidence. However, despite the urging of other characters, he initially withholds unrestricted use. His wife, Leora, accompanies Martin, but in the most tragic episode of the novel, she contracts plague, becomes septic, and dies alone in their lodge without obtaining a therapeutic phage dose. As delirium and coma set in, her husband supervised a clinical trial site in a distant village.

The novel illustrates Dr. Arrowsmith’s torn loyalties between clinical medicine and microbiological research, and underscores the competing financial interests of producing highly marketable products vs. developing “niche” treatments for uncommon diseases vs. funding other unmarketable yet basic research. Especially germane is his difficulty in conducting a proper controlled clinical trial in the midst of an epidemic, and the conflict between the urge to give unrestricted access to an unproven but potentially life-saving therapy vs. the ethical imperative to determine efficacy by withholding said drug from a control group. This conflict is emphasized when, after Leora’s death, Martin abandons the controlled trial design and offers phage to all who request it (except at one remote study site, though its villagers travel to ensure receipt of the phage and avoid the risk of being assigned to the control group), thus jeopardizing the accrual of adequate study data. Although the phage therapy appears to save lives, the final statistical analysis of available clinical trial data and conclusions regarding efficacy are never reported in the novel, but are ambiguously presented as incomplete or inconclusive:

His first task was to check the statistics of his St. Swithin treatments and the new figures still coming in from Stokes. Some of them were shaky, some suggested that the value of the phage certainly had been confirmed, but there was nothing final. He took his figures to Raymond Pearl the biometrician, who thought less of them than did Martin himself.

Martin becomes embittered as the institute’s director publishes a final report claiming success while omitting statistical analysis. The director also fails to challenge press reports that sensationalize the phage treatment as a medical wonder, prioritizing publicity over integrity.

The conundrum of clinical trial enrollment vs. unrestricted compassionate use of promising but unproven therapies has surfaced multiple times during the HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics and the 2014–2016 Ebola hemorrhagic fever epidemic in West Africa. It will continue to resurface given the open-ended challenge of emerging diseases. Controlled clinical trials are necessary as drug activity in preclinical experiments does not guarantee clinical safety or efficacy. In the present day, risks to study participants are minimized by ethical reviews of research protocols, adaptive trial designs that reduce the size of control groups, the use of comparator drugs of known efficacy (if available) in non-inferiority trials, and interim analyses of incoming data by independent study monitors; clinical trials can be halted early if analyses show either a statistically significant benefit or medical futility. Compassionate use and expanded access to investigational drugs are offered on a case-by-case basis to patients unable to enroll in clinical trials and for whom no alternatives are available.

Dr. Arrowsmith epitomizes many virtues as he strives to altruistically contribute to medicine. As a creative and courageous free-thinker, he counters the inertia arising from avarice, closed-mindedness, medical rivalries, and professional jealousy. However, Arrowsmith’s flaws, particularly those linked to interpersonal relationships and alcohol use, culminate in the novel’s disappointing conclusion. He abandons his second wife and their infant son to conduct experiments as a recluse (with one colleague) in a remote, secluded location, emerging as a self-absorbed anti-hero. Interpretations of the story may suggest that clinical practice and research can be complementary rather than antagonistic; that there is more to life than a medical career; that vocations are not obsessions; and that empathetic medical practitioners and researchers can engage others and build, rather than hinder, lasting relationships.

GEORGE CHRISTOPHER is a retired physician who specialized in infectious diseases. He lives in Michigan with his lovely wife Linda, near their two grown sons and their families.