Richard de Grijs

Sydney, Australia

In the suffocating hold of the William Nichol, twenty-year-old Sarah Dorrett lay dying. For over a year she had been “subject to cough,” but the voyage from England to Australia had hastened her decline. Surgeon-Superintendent Peter Leonard (1801–1888) watched helplessly as she passed through “every indication of tubercular disease of the lungs.”1 On November 20, 1839, after two slow months of lingering illness, she succumbed.

Sarah’s fate was far from unusual. The disease that claimed her life—known then as phthisis or consumption, the “white death”—haunted emigrant ships, convict transports, and navy vessels alike. Today, we know it as tuberculosis, a term coined by Johann Lukas Schönlein in 1834. The naval surgeon Leonard Gillespie (1758–1842) considered it one of the two deadliest afflictions aboard ship, rivaled only by rheumatism.2 From Europe to Australia, countless mariners, soldiers, convicts, and emigrants wasted away en route on their months-long voyages.

Consumption took its name from its most harrowing effect: it appeared to consume the body from within. The disease typically began with a bloody cough, advancing to fever, night sweats, emaciation, and eventually death3:

Most of them were affected by these diseases in the following manner; fevers accompanied with rigors, … constant sweats, … extremities very cold, and warmed with difficulty; bowels disordered, with bilious, scanty, unmixed, thin, pungent, and frequent dejections. The urine was thin, colourless, unconcocted, or thick, with a deficient sediment. Sputa small, dense, concocted, but brought up rarely and with difficulty; and in those who encountered the most violent symptoms there was no concoction at all, but they continued throughout spitting crude matters.4

Tuberculosis can occur in any organ, but it is best-known and infectious in the lungs, from where it can spread as a bloodborne disease. It could manifest in various forms; phthisis, phthisis pulmonalis (pulmonary tuberculosis), tabes mesenterica (mesenteric tuberculosis), and scrofula (mycobacterial cervical lymphadenitis) were all recognized as related but distinct conditions, although contemporary medical practitioners rarely connected them as variations of the same disease. So confused was its pathology that Lloyd and Coulter omitted its discussion from their authoritative Medicine and the Navy, 1200–1900, stating the “diagnosis … was so confused, and the treatment so elementary, … that worthwhile comment is impossible.”5

But for surgeons at sea, consumption was all too real: patients coughed up blood, complained of chest pains and side aches, and suffered from fevers and night sweats. Faces became florid with fever, and the classic “hectic flush” marked their cheeks. The afflicted were tormented by sleepless nights, difficulty breathing, and gradual wasting of the flesh.6

In children, tuberculosis often presented as either scrofula—swollen lymph glands in the neck—or tabes mesenterica, an abdominal form causing wasting and diarrhea. Aboard the William Nichol, Leonard recorded two-year-old toddlers with tabes mesenterica and “scrofulous habit of body” whose “puny” appearances, “much emaciated with a pale sickly countenance,” signaled both chronic infection and the harsh shipboard conditions hastening their decline.7

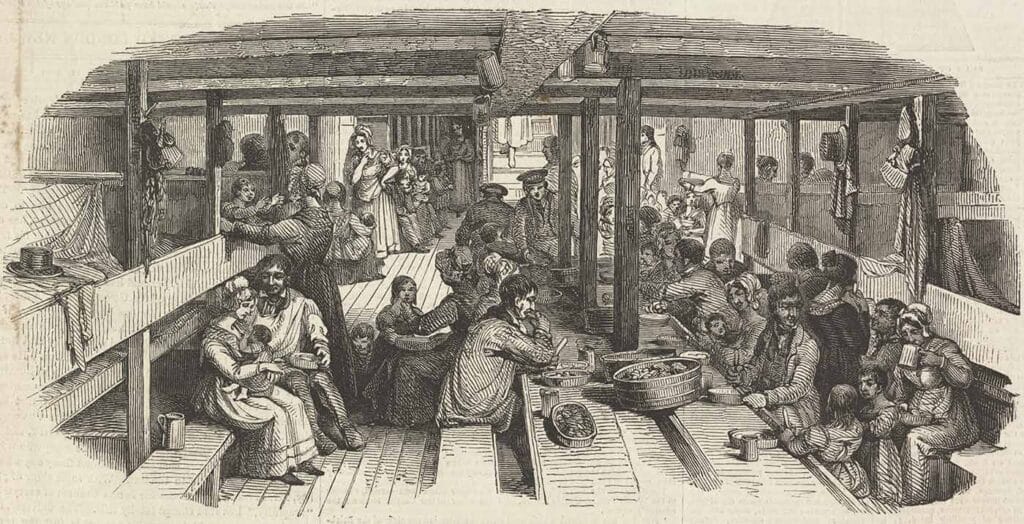

Ships became incubators for tuberculosis. The disease’s airborne transmission—through microscopic droplets expelled by coughing, speaking, or sneezing—remained unknown. Below decks, where damp bedding and crowded conditions prevailed, tuberculosis spread unseen from berth to berth. Surgeons believed that consumption was hereditary, constitutional, or the result of cold and wet conditions. Gilbert Blane (1749–1834), Scottish reformer of naval health practices, for instance, believed that “many pulmonic [afflictions] are caught by men falling asleep in the open air, on their watch.”8

Thomas Trotter (1760–1832) experimented by placing consumptive patients in the lower, oxygen-poor holds of his vessel, arguing the warmer air might help. He also identified supposed physical predispositions, noting that “persons with narrow conformation of the chest, high shoulders, long neck, smooth skin, etc.” were more likely to suffer from consumption.9 Such observations reflect the confusion of medical knowledge in the pre-bacteriological age.

Emigrant and convict vessels carried their own medical paradox. Those already infected often boarded without detection, since pre-embarkation inspections were rudimentary. In fact, sea voyages were considered beneficial to infected patients, not least because of the perceived advantages of frequent purging caused by seasickness.10 The idea that long sea voyages might cure tuberculosis sufferers was taken to its extreme in 1864, when the Brompton Hospital for Consumption and Diseases of the Chest launched its “Madeira Project.” The hospital authorities embarked some twenty infected patients on the Maria Pia destined for Madeira, in the hope that the island’s favorable climate would ease symptoms and accelerate remission. Before long, however, the hospital’s doctors concluded the voyage had not delivered on their expectations.11

The long incubation period of tuberculosis meant that many shipboard cases remained latent until physical stress and poor nutrition accelerated bodily decline. Conversely, those infected en route might only manifest symptoms months or even years later. Nonetheless, death from consumption was so common, it was routinely and dispassionately recorded in surgeons’ logs.

Amid the stifling, crowded spaces below deck, the disease found fertile ground to spread. On better-managed ships and in fine weather, bedding was aired and cleaned with a mixture of vinegar and chloride of lime. Yet, straw bedding often remained soaked in storms, and cracks in the wooden berths frequently housed lice, cockroaches, fleas, and even rats and mice. In such crowded and damp environments, influenza, pneumonia, and tuberculosis thrived.12 For many, sea voyages that were supposed to offer new life became slow passages to death.

The disease’s human toll was hidden in plain sight. Surgeon-superintendents’ journals reveal tuberculosis as a consistent, yet often unremarked, killer. On voyages to Australia, 14–19% of all deaths among convicts and emigrants were attributed directly to tuberculosis or related forms such as scrofula or tubercular meningitis; other deaths attributed to “atrophy,” “marasmus” (protein-energy malnutrition leading to chronic starvation), “convulsions,” and even “neglect” may have been linked as well. Among infants, death from tabes mesenterica was common.13

Tuberculosis in early nineteenth-century Britain killed more patients than cholera and smallpox combined.14 Poor nutrition worsened matters: underfed emigrants and convicts were highly susceptible to contracting the disease. The vicious cycle of poverty allowing the conditions to develop that facilitated the spread of tuberculosis, and of tuberculosis causing the poor health outcomes leading to further poverty was as evident aboard ship as on shore.15

Case studies from convict voyages give tuberculosis a human face. Michael McDaniel, aged fifty-four, a convict aboard the North Briton, entered the ship’s sick book in January 1843 as suffering from phthisis confirmata. He died less than a month later, with the surgeon’s journal recording his wasting body and inevitable demise.16 Nor was tuberculosis confined to convicts and emigrants. Soldiers, sailors, and firemen fell victim, too.

In early 1909, fireman (stoker) Sheikh Ebrahim Sheikh Mahomed died aboard the steamer Singapore, after months of illness, initially thought to be acute rheumatism but diagnosed post-mortem as consumption. Around the same time, another stoker, Man Kai, died of phthisis aboard the steamer Peleus after only six weeks at sea on a voyage from Liverpool to Japan. Neither man had been isolated, and medical examinations before boarding had failed to detect their infections.17 Naval surgeon Gillespie lamented that consumption and rheumatism accounted for the greatest number of invalids or mortalities in the fleet, particularly among older sailors.18

In settler communities, tuberculosis remained endemic. In early America, a deep, “hacking” cough was as common as gray hair among the elderly. Before Robert Koch (1843–1910) identified Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 1882, the disease’s origins were so mysterious that New Englanders suspected vampirism; villagers exhumed the dead and mutilated their corpses in futile attempts to halt familial outbreaks of consumption.19

Aboard ship, such superstitions had little influence. Treatments were limited to ingesting cod liver oil, tobacco smoke or turpentine vapor inhalation, and dubious dietary remedies such as consuming thick, boiled-down onion stew. Until the development of the antibiotic streptomycin in 1946, the only effective treatment of infected patients was quarantine. But as the disease was not considered contagious, patients typically remained among their fellows until death. As a case in point, after Captain James Cook’s violent death in 1779, Lieutenant Charles Clerke (1741–1779) was made captain, but he soon succumbed to consumption:

… his very gradual decay had long made him a melancholy object to his friends; yet the equanimity with which he bore it, the constant flow of good spirits which continued to the last hour, and a cheerful resignation to his fate afforded some consolation. The vigour and activity of his mind had in no shape suffered from the decay of his body.20

The decline of tuberculosis during the nineteenth century was not because of improved treatment, but rather from rising living standards, better nutrition, and changes in public health. Emigrant and convict ships, however, lagged in these improvements. Crowded, poorly ventilated, and populated by the undernourished, they remained hotbeds of the disease well into the late nineteenth century.

In surgeon’s logs and death registers, tuberculosis appears as a recurring yet unremarkable entry. But for patients like Sarah Dorrett and Michael McDaniel, the experience was anything but mundane. Wasting slowly in the dark holds, tormented by cough and fever, they died far from home, watched over by surgeons who could only document their decline. Tuberculosis sailed with them from Britain’s ports. It lingered in the damp bedding, breathed in the stale air of crowded berths, and claimed its victims quietly, steadily, as ships crept towards their far-flung destinations.

Consumption, aptly named, consumed not just bodies but hope itself. Among sailors and emigrants, it became known as the robber of youth, the graveyard cough, and the king’s evil.21 It was, as one poet later wrote, the “Captain of all these men of Death.”

References

- Leonard, P. Surgeon-superintendent’s journal on board the government emigrant ship Orestes, 1839. Australian Joint Copying Project (AJCP); Public Records Office (PRO), Nos. 3189–3214. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales (SLNSW).

- Brockliss, L, Cardwell, J, and Moss, M. Nelson’s Surgeon. William Beatty, Naval Medicine, and the Battle of Trafalgar (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 101.

- Convertito, C. The Health of British Seamen in the West Indies, 1770–1806 (PhD Thesis, University of Exeter, UK), 82.

- Hippocrates (460–370 BCE). “Book 1. Of the Epidemics.” In: Adams, F (transl.), The Genuine Works of Hippocrates (London: The Sydenham Society, 1849); facsimile edition (Birmingham, AL: The Classics of Medicine Library, 1985), 352–354.

- Lloyd, C, and Coulter, JLS. Medicine and the Navy 1200–1900, 3 (Edinburgh: E&S Livingston, 1961), 348.

- Convertito, The Health of British Seamen, 82.

- Roberts, G. Surgeon-superintendent’s journal on board the government emigrant ship William Nichol, 1839. AJCP PRO 3189–3214, SLNSW.

- Blane, G. Observations on the Diseases of Seamen (London: John Cooper, 1789), unpaginated.

- Finlayson, R. An Essay Addressed to Captains of the Royal Navy, and those of the Merchants’ Service; on the Means of Preserving The Health Of Their Crews (London: Thomas and George Underwood, 1824), 4.

- Haines, R. Doctors at Sea: Emigrant Voyages to Colonial Australia (Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 42.

- Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, Royal Brompton Hospital. https://guysandstthomas.shorthandstories.com/royal-brompton-hospital/index.html. Accessed July 17, 2025.

- Immigration Museum, Journeys to Australia, 1850s–70s (Museums Victoria, 2025). https://museumsvictoria.com.au/immigrationmuseum/resources/journeys-to-australia/. Accessed July 17, 2025.

- Staniforth, M. “Diet, disease and death at sea 1837–39,” Int’l J. Maritime Hist., VIII, 119–156 (1996).

- Smith, FB. The People’s Health 1830–1910 (London: Croom Helm, 1979), 79.

- Staniforth, “Diet, disease and death at sea,” Op. cit.

- Oldman, D. North Briton 1842/43, Redcoat Settlers in Western Australia 1826–1869. https://redcoat-settlerswa.com/ships/north-briton-1842-43/. Accessed July 17, 2025.

- UK Parliamentary Debates (Hansard), vol. 10, cc2309–15: September 16, 1909. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1909/sep/16/asiatics-in-mercantile-marine. Accessed July 17, 2025.

- Brockliss et al., Nelson’s Surgeon,101.

- Tucker, A. “The Great New England Vampire Panic,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2012. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-great-new-england-vampire-panic-36482878/.

- Snell, WE. “Captain Cook’s surgeons,” Medical History, 7, 43–55 (1963), 53.

- Frith, J. “History of Tuberculosis. I. Phthisis, consumption and the white plague,” J. Military Veterans’ Health, 22(2), 29–35 (2014).

RICHARD DE GRIJS, PhD, is a professor of astrophysics and an award-winning historian of science at Macquarie University (Sydney, Australia). With a keen interest in the history of maritime navigation, Richard is a volunteer guide on Captain Cook’s (replica) H.M. Bark Endeavour at the Australian National Maritime Museum. He also regularly sails on the Museum’s replica Dutch East Indiaman, Duyfken.