JMS Pearce

Hull, England

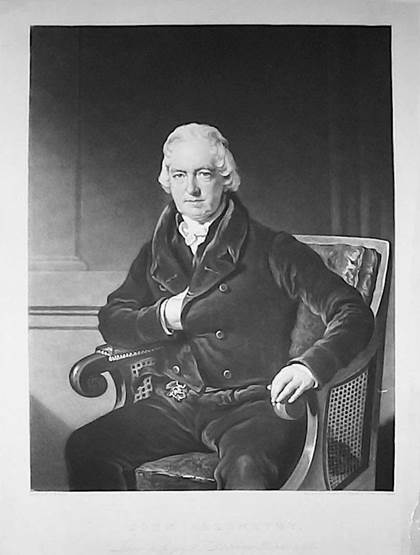

John Abernethy (1764–1831) was renowned more for his brilliant teaching than for his surgical skills, but as an eccentric and gifted communicator, he attracted many students and admirers.1 A stalwart of medical education, he was a founder of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital medical school. Yet, at times he was fractious, peevish, and prone to disputes and controversy.

John Abernethy was born in London in 1764 and attended Wolverhampton Grammar School. Attracted to medicine, he was apprenticed to Sir Charles Blicke at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital and remained there for the rest of his life. His youthful curiosity was heightened by the discoveries and ideas of Blicke and the renowned Percivall Pott (1714–1788) at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, Sir William Blizard at the London Hospital, and by the great anatomist and surgeon John Hunter (1728–1793) whom he revered for his practices of observation and experiment.

In 1787, Blicke succeeded Percival Pott and Abernethy replaced him as assistant surgeon. He was not promoted to full surgeon at the hospital until 1815, retiring in 1827. He was elected FRS in 1796, and professor of Anatomy and Surgery at the Royal College of Surgeons of England (1814–1817). He gave private anatomy lectures at his house in Bartholomew Close. They were highly praised for his direct if at times dogmatic delivery. Sir Benjamin Brodie (1783–1862) in his autobiography commented:

His lectures were full of original thought, of luminous and almost poetical illustrations … and amusing anecdotes . . . Like most of his pupils, I learned to look upon him as a being of a superior order.

He inspired many aspiring young surgeons. His lectures were so popular that the St. Bartholomew’s governors built a lecture theater within the hospital to accommodate the classes. In 1822, he persuaded the Bart’s hospital governors to give formal recognition to the medical school.

Abernethy was strongly influenced by John Hunter. He was reported as a not particularly skillful surgeon, although he secured a thriving lucrative private practice despite his reputed plainness of speech with his patients, and dogmatic and sometimes contemptuous assertions. Perhaps his peers were envious of his prowess, for he was acknowledged as one of the most famous surgeons of the day.2 He cared for the rich and the poor, but not alike: he favored with kindness and attention the poor on the wards because they had no choice in consultants. George Macilwain’s Memoirs of John Abernethy observed, “In everything Abernethy did, we find evidence of the acuteness of his mind, and his general qualifications for philosophical research.”3

Reading his texts, it is obvious that he was a dedicated, thinking surgeon, carefully considering the pathology of the healing processes and their breakdown. His appeal and success were largely attributable to his intellect, strength of character, and persuasive powers of prose and speech. He was most industrious, and it was said that not even on his wedding day did he fail to give his usual daily lecture at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital.

John Hunter performed five operations (three successful) of proximal arterial ligation for symptomatic popliteal aneurysm in 1785. Following his example, Abernethy in 1797 tied the external iliac artery proximal to an aneurysm.6 (pp. 236-50) He also ligated the common carotid artery of a man who was gored in the neck by a bull, though the patient later succumbed to “a stroke.” Abernethy instigated incision and drainage for the treatment of lumbar abscesses, which since he described them as tracking along the psoas muscle from a carious vertebra,4 may have been tuberculous. He wrote papers on many topics, including head injuries, sinusitis, and tumors.

He reported in 1793 an infant with a rare absence or hypoplasia of intrahepatic portal veins, leading to perfusion of the liver via an extrahepatic porto-systemic shunt5; it is known as the Abernethy Malformation.

His surgical experiences were published in his books Surgical Observations on the Constitutional Origin and Treatment of Local Diseases and on aneurisms (1809),6 which adumbrated The surgical and physiological works (1830).7 He published the first classification of tumors based on pathologic anatomy, Surgical observations, containing a classification of tumours, in 1804.

In his Hunterian oration of 1819, Abernethy maintained that the distinction between physic (medicine) and surgery was largely arbitrary: “Medicine is one and indivisible … The physician must understand surgery, and the surgeon the medical treatment of disease.”

Far ahead of his time, he stressed the role of constitutional origin in disease, often choosing the limited conservative treatments then available, before embarking on surgery. Abernethy was one of the first surgeons to treat selected patients expectantly rather than by operation—possibly because he wisely realized the limited success of many surgical procedures in the absence of modern-day anesthesia, antibiotics, and blood transfusion.

His texts are thoughtful, critical of others, but also of himself; they insisted on experience of individual cases rather than ill-founded speculation in proving a general principle or rule. Many ailments he related to poor personal habits, diet and lifestyle, which (unusually at that time) he attempted to correct.8 He noted: “The proposition is this: —I say that Local disease, injury, or irritation, may disturb the whole system, and conversely, disturbance of the whole system, may affect any part.” (Surgical Lectures)3

In a much-publicized Abernethy–Lawrence controversy, Abernethy philosophically invoked an immaterial principle of vitality pervading the organism. This was opposed by William Lawrence (1783–1867), a surgeon ophthalmologist (President of the Royal College of Surgeons and Serjeant Surgeon to Queen Victoria), who believed in a more organic materialism of these vital phenomena, though both men preached and practiced localization of function and pathology.

A disputatious saga arose when in 1824 Thomas Wakley, editor of the newly established Lancet, published Abernethy’s lectures without his permission. Abernethy took umbrage and sought an injunction to prevent the Lancet from publishing the lectures. The Lord Chancellor refused. A second application was successful and the Lord Chancellor then decreed that lectures could not be published for profit. This formed the precedent for subsequent copyright rulings. The controversy between Abernethy and Wakley represented a struggle between traditional medical practices and reformers advocating openness, accountability, and modernization, especially in the Royal College of Surgeons. Wakley campaigned against apprenticeship and pupillage based on nepotism and patronage.

Abernethy lost his Royal Appointment to George IV after refusing to attend the King’s bedside until after he had completed giving his lecture at Barts. Abernethy tried to get his son appointed as a future lecturer, which provoked a scandal at Barts.

In spite of his controversial reputation, he became president of the Royal College of Surgeons in July 1826 shortly after Thomas Wakley’s attack on the celebrated Astley Cooper and on the College:

[We deplore the] State of society which allows various sets of mercenary, goose-brained monopolists and charlatans to usurp the highest privileges…. This is the canker-worm which eats into the heart of the medical body. (Wakley T. Lancet 1838–39, 1, p 2–3.)

The College housed John Hunter’s impressive collection. Abernethy appointed Robert Willis as Librarian in 1828 and Richard Owen (1804–1892), the eminent comparative anatomist, as second Assistant Conservator in the Hunterian Museum.

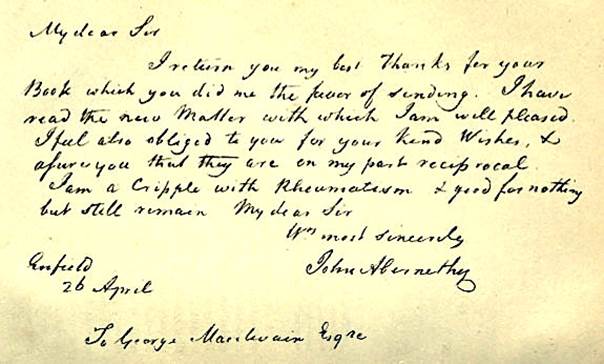

He retired in 1827 and resigned as an examiner at the Royal College of Surgeons two years later. Essentially, he was a benevolent man of great moral integrity, kind and generous to those in need of help, though quick to refute ill-considered ideas and humbug.3 By 1829, his health deteriorated and he wrote to his biographer, George Macilwain, declaring himself a cripple with rheumatism:

He retired to Enfield, where he died on 28 April 1831. He was buried at Enfield parish church, and was survived by his wife Anne (née Threlfall) and their three daughters.

The Duke of Sussex, president of the Royal Society, portrayed him in his address in November 1831:

Mr Abernethy was one of those pupils of John Hunter who appears the most completely to have caught the bold and philosophical spirit of his great master … As a lecturer, he was not less distinguished than as an author. He enjoyed more than an ordinary share of public favor in the practice of his profession; and, though not a little remarkable for the eccentricities of his manner and an affected roughness in his intercourse with his ordinary patients, he was generally kind and courteous in those cases which required the full exercise of his skill and knowledge, and also liberal in the extreme when the infliction of poverty was superadded to those of disease.

References

- King L. Saints and Sinners: John Abernethy. The Royal College of Surgeons of England Bulletin, vol. 94, no. 6, 2012.

- Lawrence, S. Charitable Knowledge: Hospital Pupils and Practitioners in Eighteenth-Century London. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. p. 327-31.

- Macilwain G. Memoirs of John Abernethy, with a view of his lectures, his writings, and character; with additional extracts … London: Hatchard & Co. 3rd edition, 1856.

- Abernethy J. Surgical observations on tumours, and on lumbar abscesses. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown 4th edition 1817.

- Abernethy J. Account of two instances of uncommon formation in the viscera of the human body. Phil Trans Royal Society. 1793, 83: 59-66.

- Abernethy J. Surgical Observations on the Constitutional Origin and Treatment of Local Diseases and on aneurisms London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1809.

- Abernethy J. The surgical and physiological works of John Abernethy. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1830.

- Thornton JL. John Abernethy: A Biography. London: Simpkin Marshall Ltd., 1953.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Leave a Reply