JMS Pearce

Hull, England

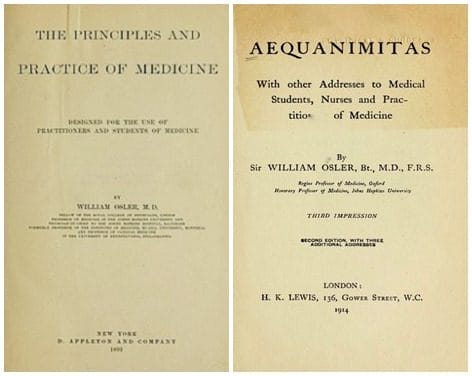

Amongst many books and essays devoted to the ideology and practice of medicine in its widest sense, William Osler’s Aequanimitas1 stands out as a classic. Influenced by Sir Thomas Browne’s Religio Medici, published in 1686, Osler’s Aequanimitas with Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine was published in 1904. It was based on his farewell address in 1889 at the Pennsylvania School of Medicine, before his appointment as Physician-in-Chief at Johns Hopkins, and later as Regius Professor of Physic at Oxford.2,3

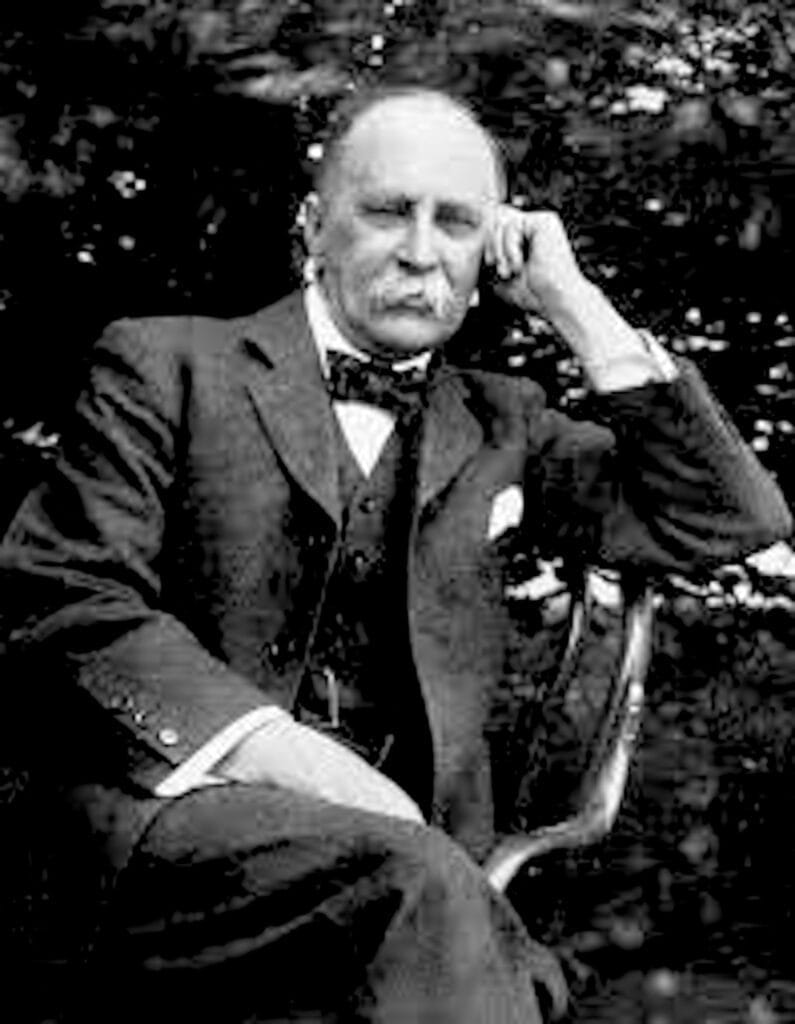

Trained at Toronto and McGill Universities, William Osler (1849–1919) was one of the most exalted of physicians, a superb clinician and bedside teacher. Just two words are the essence of these elegantly penned essays: aequanimitas and imperturbability. He set out the principles of a rational and questioning clinical approach to patients’ illnesses. He stressed the need for humanity, integrity, and the singular importance of the physician’s appearance and behavior. His demeanor should appear serene and imperturbable—“a bodily endowment”—in order to avoid emotional involvement, which might impair his judgment:

Coolness and presence of mind under all circumstances, calmness amid storm, clearness of judgment in moments of grave peril, immobility, impassiveness, or, to use an old and expressive word, phlegm.

Aequanimitas—“the mental equivalent of imperturbability”—embodied a degree of detachment,4 a balance between compassion and resilience. He realized the difficulties of always maintaining such standards, and candidly admitted, “While preaching to you a doctrine of equanimity, I am, myself, a castaway. Recking not my own rede [advice], I illustrate the inconsistency which so readily besets us.” His use of the phrase “imperturbability with a tender heart” appeared paradoxical but signified an emotional strength necessary in the doctor. Aequanimitas was occasionally criticized for preaching in a snobbish, portentous fashion. But this was the conventional authoritarian style of doctors of his day, and his fundamental wisdom is inescapable.5

In Aequanimitas he advocated the principles not only to doctor-patient encounters but also to the doctor’s behavior in his private life. Osler was outwardly urbane, cheerful, and witty, but those who knew him well2 were aware of his many personal difficulties, not least his prolonged grief at the death of his son, Edward Revere Osler, in the First World War.

At a farewell dinner in 1905, he shared his personal ideology:

I have three personal ideals. One, to do the day’s work well and not to bother about tomorrow…The second ideal has been to act the Golden Rule, as far as in me lay, toward my professional brethren and toward the patients committed to my care. And the third has been to cultivate such a measure of equanimity as would enable me to bear success with humility, the affection of my friends without pride, and to be ready when the day of sorrow and grief came to meet it with the courage befitting a man.

The twenty-two addresses in this book, he observed, were delivered at sundry times and in diverse places. They tend to paternalism, but deal with the many daily problems and competing attitudes of medical practice, laden with erudite literary and classic quotations, wisdom, and clinical acumen. So many issues such as mental health, euthanasia, and non-medical practices resound today. His titles included: Teacher and student; Physic and physicians as depicted in Plato; Teaching and thinking; Unity, Peace and Concord; Internal medicine as a vocation; Books and men; and The master-word of medicine.

It is difficult to write about Osler without quoting his aphorisms,3 many contained in Aequanimitas:

The good physician treats the disease; the great physician treats the patient who has the disease.

He was cautious of adhering too much to written dogma when he said:

He who studies medicine without books sails an uncharted sea, but he who studies medicine without patients does not go to sea at all.

Inclined to therapeutic nihilism, he said:

The person who takes medicine must recover twice, once from the disease and once from the medicine.

For Osler, the practice of medicine was “an art, not a trade; a calling, not a business; a calling in which your heart will be exercised equally with your head.” Reflecting the attitudes of the time, he said, “Often the best part of your work will have nothing to do with potions and powders, but with the exercise of an influence of the strong upon the weak, of the righteous upon the wicked, of the wise upon the foolish.”

One marvels at how he made time in such a busy life to explore so deeply his favorite authors: Plato, Marcus Aurelius, Epictetus, Montaigne, Shakespeare, Emerson, Keats, and Shelley. He was a curator of the Bodleian Library and bequeathed his vast personal collection of books to McGill University. He compiled a large number of biographical essays of medical and literary figures.6 Of many unrivalled contributions to medicine and medical education was his textbook, The Principles and Practice of Medicine, completed single-handedly within two years, which reached a sixteenth edition in 1947.7,8

Osler was an exceptionally skilled physician, teacher, and humanist. He died after surgery for empyema complicating pneumonia four days after Christmas in 1919. Countless honors bestowed on him reflected the adulation of his colleagues and pupils. His inspiration advanced medicine far beyond Canada, the USA, and Britain. He showed an engaging modesty, love of practical jokes, kindly humor, and an unswerving humanity.9 The Lancet described him as “the greatest personality in the medical world at the time of his death.”

The motives that inspired Aequanimitas were revealed when he said, “I desire no other epitaph than the statement that I taught medical students in the wards, as I regard this as the most useful work that I have been called upon to do.”

References

- Osler W. Aequanimitas, With Other Addresses to Medical Students, Nurses and Practitioners of Medicine. London: HK Lewis, 1904.

- Cushing, H. The life of Sir William Osler, vols. 1 & 2. London, New York, & Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1940.

- Dunea G. William Osler. Hektoen International, Fall 2021.

- Rodin AE, Key JD. William Osler and Aequanimitas: an appraisal of his reactions to adversity. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 1994;87:758-63.

- Bliss M. William Osler: A Life in Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Garrison FH. Sir William Osler’s Contributions to Medical Literature. Ann Med Hist. 1919;2(2):184-7.

- Osler W. The principles and practice of medicine. New York & London: D. Appleton and Co, 1892.

- McGehee Harvey A, McKusick VA, eds. Osler’s Textbook Revisited: selected sections with commentaries. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1967.

- Brown GH. Munks Roll: Inspiring Physicians, the Royal College of Physicians, vol IV. 1849-1919: 295.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.