JMS Pearce

Hull, England

In 1924, London’s National Gallery received a bequest from the Mond family, an oil painting titled Portrait of Girolamo Fracastoro, attributed to Titian about 1528. What special attributes of a Veronese physician made him a suitable subject for the renowned artist Titian?

Girolamo Fracastoro or Hieronymus Fracastorius (1483–1553) became famous because his Latin poem Syphilis, sive Morbvs Gallicvs (1530) gave us the name syphilis, which then fell into common usage.

The art historian Vasari confirmed Titian’s portrait in the 1568 edition of his Lives of the Artists. The National Gallery’s description1 tells how before it was conserved, the painting was in poor condition and its attribution to Titian was doubted. It records how recent conservation treatment had revealed Titian’s touch, particularly apparent in the lynx fur collar and in the subject’s pose, looking over his shoulder with his arm resting on a parapet, reminiscent of Titian’s Portrait of Gerolamo Barbarigo (c. 1510), one of Titian’s friends. This posture was to be a model for self-portraits of Rembrandt, Van Dyck, and Joshua Reynolds.

Syphilis

The first known description of syphilis is that of the Venetian military surgeon Marcello Cumano in 1496, who observed soldiers afflicted by painless ulceration on the penis. Sores and pustules then appeared all over the body, accompanied by joint pains. Cumano’s contemporary, Giovanni da Vigo, also described the primary chancre on the genitalia followed by a latent period and the secondary stage of the disease.2

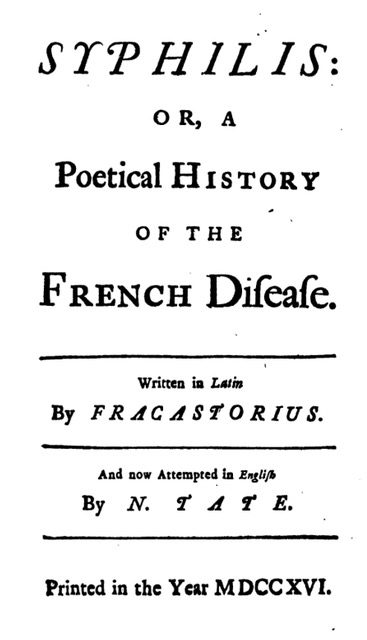

Fracastoro studied at Padua, a contemporary and friend of Nicolaus Copernicus. Immediately after graduating, aged nineteen in 1502, he was appointed Instructor in Logic. An astronomer and poet of Verona, he was also an accomplished physician. His three-volume poem Syphilis, sive Morbvs Gallicvs (1530) was translated by Nahum Tate (Fig 2) in 1686: Syphilis: or, a Poetical History of the French Disease.3

The poem tells of a sailor who sailed westward from Spain to a mighty island in the middle of the sea. The crew shot the birds native to the island of Ophir, which belonged to Apollo, the sun god. Only one bird escaped and prophetically threatened:

Nor end your sufferings here; a strange Disease,

And most obscene, shall on your Bodies seize…

The subject, a shepherd named Syphilus, offended Apollo, who for revenge, afflicted Syphilus with the disease:

Th’all seeing Sun no longer could sustain

These practices, but with enrag’d Disdain

Darts forth such pestilent malignant Beams,

As shed infection on Air, Earth and Streams;

From whence this Malady its birth receiv’d,

And first th’offending Syphilus was griev’d,

Who rais’d forbidden Altars on the Hill,

And Victims bloud with impious Hands did spill;

He first wore Buboes dreadfull to the sight,

First felt strange Pains and sleepless past the Night;

From him the Malady receiv’d its name.

Book III, 321-32.

In the first book, the poem records an incubation period between acts of venery and the onset of the primary genital chancre. In the second book, he describes its infective nature: seminaria contagiosum, and its clinical features4:

Immediately unsightly sores broke out over all the body and made the face horrifyingly ugly, and disfigured the breast by their foul presence: the disease took on a new aspect: pustules with the shape of an acorn-cup and rotten with thick slime, which soon afterwards gaped wide open and flowed with a discharge like mucous and putrid blood…Moreover the disease gnawed deep and burrowed into the inmost parts, feeding on its victims’ bodies with pitiable results.5

He considered treatment with mercurials and guaiac obtained from the sacred wood of the American Indians.

Syphilis in literature

Syphilis was thought to be an infection of ancient Chinese dynasties, others suggested the early Romans. The sailors with Columbus’s fleet were said to have brought the disease to Spain in 1493. During Charles VIII’s Italian War in 1494–95, syphilis infected many French troops in Naples and quickly spread across Europe. The mercenaries in 1496, aided by James IV of Scotland, invaded England; they bore both arms and the “grandgore” (Old French: grand + gorre = syphilis).

The source of the name syphilus is disputed. It has been suggested that it is a corrupted medieval form of Sipylus, the son of Niobe (named after a mountain described by Ovid). Syphilis acquired many other names: the Spanish pockes; the Neapolitan itch; morbus Gallicus, the French disease; grandgore; and pockis or pox. Pock-royal was the satirical name for a pustule of the great pox (syphilis) as opposed to the smallpox. W. Gurnall described the association with intercourse and the notion of sin in 1662: “What a beauty Man was, till he was pock-broken (if I may say so) by sin.” Other euphemisms developed. It is still referred to as Lues from lues the plague and Lues venerea (venereal plague). The coiled spirochetes of Weil’s disease, relapsing fever, as well as syphilis were described in 1876. The more specific name treponema was coined from the word for a thread in 1905. Another euphemism, “specific disease,” was caused by the infection with Treponema pallidum (Spirocheta pallidum). Three stages of syphilis were distinguished, primary, secondary, and tertiary: the first characterized by a chancre in the part infected, the second by eruptions of the skin and mucous membranes, the third by gummata, involving the aortic valve, bones, and brain.

Paul Wassermann (1866–1925) devised the Wassermann Reaction (WR) in 1906, in which antibodies to the organism were detected by complement fixation. Many other tests developed until the more specific flocculation absorption test and the treponemal immobilization tests and variations, which are in common use.

For decades, the nineteenth-century treatment with toxic arsenicals, mercury, and malaria-therapy were in vogue, but of little benefit. Not until 1948 was penicillin used, which revolutionized treatment and offered a means of curing the disease.

Contagion

In the sixteenth century, infectious diseases were thought to result from miasma or bad air. Fracastoro’s major work De contagione… (1546)6 discussed the nature and the spread of infectious diseases, remarkably foretelling the germ theory of disease initiated late in the nineteenth century by Lister, Koch, and Pasteur. He thought rabies was transmitted “when the skin is so lacerated by the dog’s bite that blood is drawn just as though the contagion occurs in the blood itself by the contact of the tooth and spume of the rabid animal.”

He suggested that epidemic diseases could be transmitted by contagion caused by “seeds”—rapidly multiplying minute bodies—either by direct contact or through the air or by soiled clothes or linen, which he called fomites from the Latin fomes meaning tinder.7 This was disputed by Giambattista da Monte, among others, who argued that contagion was caused by the degree of putrefaction caused by direct or by airborne contact.8

His theory of epidemics spread by contagion was wholly neglected.9 Vivian Nutton accurately described him as a man before his time, misunderstood and neglected by lesser writers who did not appreciate the validity of his ideas.8

He made other prescient but unrecognized contributions. For example, in excavations in Verona in 1517, many curious fossil mussels were exposed. Rejecting theories of a “plastic force” or a sequel to Noah’s flood, Fracastoro postulated (following Leonardo da Vinci and anticipating Alfred Russel Wallace [1823–1913] and Darwin) that these fossils belonged to animals, which had formerly lived and multiplied in that place. Like his theories of contagion, his opinions were disregarded.

Fracastoro died of a stroke in 1553 and was buried in Verona, where his statue (Fig 3) stands high above a beautiful arch in the central Piazza dei Signori.

References

- National Portrait Gallery. Portrait of Gerolamo Fracastoro. Titian. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/titian-portrait-of-girolamo-fracastoro

- Tognotti, E. The Rise and Fall of Syphilis in Renaissance Europe. J Med Humanit 2009;30, 99-113.

- Fracastoro, Girolamo, and Nahum Tate. Syphilis, or, A poetical history of the French disease written in Latin by Fracastorius ; and now attempted in English by N. Tate. Oxford Text Archive, 2003. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12024/A40375

- Pearce JMS. A note on the origins of syphilis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998 Apr;64(4):542, 547.

- Eatough G. Fracastoro’s Syphilis. Introduction, Text, Translation and Notes. Francis Cairns Publications, 1984.

- Fracastoro G. De contagione et contagiosis morbis et curatione libri iii, heredes Lucaeantonii Iuntae.Florentini, Venetiis, 1546.

- Dunea G. Fracastorius, the man who named syphilis. Hektoen International Summer 2016.

- Nutton, Vivian. The Reception of Fracastoro’s Theory of Contagion: The Seed That Fell among Thorns? Osiris. 2nd Series, Vol. 6, Renaissance Medical Learning: Evolution of a Tradition. University of Chicago Press 1990;196-234.

- Singer C, Singer D. The Scientific Position of Girolamo Fracastoro. Annals Med. Hist. 1917;1:1-34.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.