Joseph Lockhart

Saty Satya-Murti

California, United States

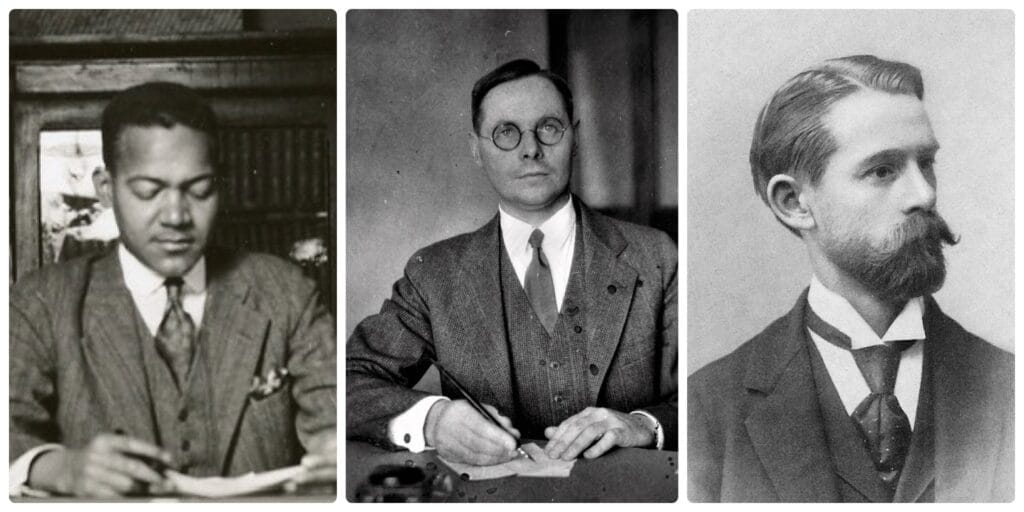

Few adherents of pseudoscientific beliefs have wreaked as much societal and human damage as did the eugenicists during the first half of the 20th century. In America, these beliefs led to large-scale sterilization, immigration controls with flimsy rationales,1 and support of racist education and funding.2 Worldwide, they set the stage for Nazi sterilization under the Nuremberg laws and racial genocide. Although there were many early promotors of eugenics such as Paul Popenoe, scientists such as biologist H.S. Jennings and psychologist Horace Mann Bond (Fig 1) called for a skeptical view of eugenic claims.2,3

Eugenics was racist and classist from its beginning,4-7 yet many eugenicists had scientific training. Why did these scientists have such a difficult time letting go of their eugenic beliefs, which by the late 1920s to 1930s could better be considered a pseudoscience?

It might be argued that in their nascent stage of 1900–1920, eugenic theories had not yet had the opportunity to be disproven by later scientific studies. We examined this question by analyzing the contents of a well-known American pro-eugenic genetics journal of that period. The views of its editor, in contrast to two prominent scientists and mainstream genetics highlight the length to which eugenicists were willing to distort empirical findings.

The Journal of Heredity was overseen by Paul Popenoe (1888–1979) from 1916 to the 1940s.8-10 Popenoe was an ardent eugenicist, later reinventing himself as a TV marriage counselor.11 While purportedly guided by scientific principles, Heredity was a mouthpiece for eugenics until at least the 1930s. (It is now a respected scientific journal, having moved on from its eugenic past.)

In contrast, another American journal, Genetics,12 focused on basic research, using plant or animal models such as drosophila. Genetics and Heredity took drastically different trajectories, one mired in defending pseudoscientific eugenics, the other making steady scientific progress.

Early eugenic beliefs, Heredity, and Paul Popenoe

Eugenicists initially suggested that nearly all biological and psychological differences, ranging from socioeconomic status, intelligence, mental illness, and susceptibility to disease, were attributable to genetic differences.4,13 Beliefs included the “unit-hereditary” assumption, that a small number of genes controlled differences underlying complex traits such as intelligence.4,5,9,14,15 Thus, proscriptions against marriage and childbearing were advocated not just for epilepsy or “feeblemindedness,” but also for tuberculosis or criminal history.

Paul Popenoe gained an outsized influence in eugenics as editor of the Journal of Heredity. Although not a formally trained scientist, Popenoe’s interest in plant and animal breeding spurred his eugenic advocacy of forced sterilization in humans.16 In 1916, he changed the journal’s name to reflect increased interest in eugenics. Heredity’s purpose was “…promoting a knowledge of the laws of heredity and their application to the improvement of plants, animals, and human racial stocks.” Popenoe remained on the editorial board throughout the 1940s.10

1924: The weight of anti-eugenic evidence

When should Heredity have realized the weight of evidence was against them, but still decided to publish pseudoscientific eugenics articles? We suggest a potential inflection point occurred in 1924. At that time, the respected biologist H.S. Jennings (1869–1947) wrote a seminal article in Scientific Monthly (later Scientific American).3 Earlier, Jennings had courageously pointed out unscientific racial assumptions of immigration policy to the U.S. Congress.16 In Scientific Monthly, Jennings drew from cytology, embryology, and psychological studies. He undercut the idea of examining traits outside of their environment, attacking the unit theory of inheritance for intelligence and other traits. Jennings argued that genes and environment were deeply intertwined, with no “bright line” to distinguish their differential effects. He called prevailing eugenic ideas regarding immigration policy “empty and idle.”

In 1924, Horace Mann Bond (1904–1972) was a young African American psychologist (and later social scientist and college administrator).7 Bond effectively challenged the validity of the Yerkes Army IQ testing and its racist conclusions.2 He did this by highlighting the vast educational and environmental disparities between the White and Colored educational systems. Bond suggested that by 1924, Popenoe’s science was flawed and not worthy of serious consideration. Yet despite Jennings’ and Bond’s devastating criticisms of eugenics, Heredity made little attempt to moderate their most extreme claims.

Heredity before and after Jennings and Bond

The May 1923 issue of Heredity discusses the danger of low birth rates among college-educated, showing a picture of a large White college-educated family, titled: “No racial suicide here” (see Fig 2). Other articles include a review of differential fertility among social groups,17 bemoaning couples that “from a eugenic point of view, ought to be parents but are not.”

That Jennings’ 1924 article had little impact on Heredity is demonstrated in a 1935 issue. The December issue includes a lengthy, positive review of the first year of German sterilization,18 p. 485 chillingly dismissing concerns of genocide:

While there is no way to prove that such may not be the case, a certain amount of indirect evidence has been obtained which strongly supports the view that the German authorities have made a sincere attempt to apply the principles of the sterilization law in a just and enlightened manner. No serious evidence that it has been used improperly as a “racial purifier” has been noted.

By 1939, interest in eugenics had waned enough19 so that Heredity relegated eugenics to a quarterly section. Still, some of the most racist eugenics articles remained to be published.

The April 1942 edition of Heredity (with Popenoe and his father still at the helm) details Tage Ellinger’s visit to the German Institute of Anthropology, whose purpose was “…eliminating from that nation the hereditary attributes of the Semitic race.”20 p. 142 Ellinger goes on to say:

What I saw in Germany often made me wonder whether the subtle idea behind the treatment of the Jews might be to discourage them from giving birth to children doomed to a life of horrors. If that were accomplished, the Jewish problem would solve itself in a generation, but it would have been a great deal more merciful to kill the unfortunates outright.

Eugenic ideas after the 1940s

Over time, Heredity shed its eugenic past and embraced basic science. Yet, these early missteps corrupted scientific knowledge and promoted false information, allowing eugenicists to falsely claim their ideas were still “scientific.” In contrast, journals like Genetics made significant advances through their focus on fundamental science. Following World War II, public advocacy for large-scale sterilization fell out of favor, and was replaced with calls to promote childbearing among eugenically “fit” couples and decrease dysgenic divorce.11 Popenoe went on to host Can This Marriage be Saved? and established the American Institute of Family Relations in California.

It is tempting to suggest that eugenic ideas never fully died, and that veiled eugenic policies and racist research continue to this day.6,21–25 Several experts have cautioned against a return to misappropriation of science in misusing modern genetic techniques. While these new arguments may be couched in different language, the underlying assumptions and core motivations appear eerily similar to errors highlighted by Bond and Jennings a century ago.

References

- Brigham CC. Intelligence Tests of Immigrant Groups. Psychological Review. 1930;37:158.

- Bond HM. Intelligence Tests and propaganda. The Crisis. 1924;28(1):61-64.

- Jennings HS. Heredity and environment. The Scientific Monthly. 1924;19(3):225-238.

- Cravens H. The Triumph of Evolution: The Heredity–Environment Controversy, 1900–1941. Johns Hopkins University Press; 1978.

- Galton F. Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope, and Aims. American Journal of Sociology. 1904;10(1):1-25. doi:10.1086/211280

- Gould SJ. Mismeasure of Man. WW Norton & company; 1996.

- Urban WJ. The black scholar and intelligence testing: The case of Horace Mann Bond. J Hist Behav Sci. 1989;25(4):323-334. doi:10.1002/1520-6696(198910)25:4<323::AID-JHBS2300250403>3.0.CO;2-J

- Journal of Heredity | Oxford Academic. OUP Academic. Accessed August 4, 2024. https://academic.oup.com/jhered/jhered

- Popenoe P, Johnson R. Applied Eugenics. Macmillan; 1918.

- Spitzzeri P. The Slippery Slope of Social Engineering: The Case of Paul B. Popenoe, 1915-1930. The Homestead Blog. February 28, 2020. Accessed July 31, 2024. https://homesteadmuseum.blog/2020/02/27/the-slippery-slope-of-social-engineering-the-case-of-paul-b-popenoe-1915-1930/

- Ladd‐Taylor M. Eugenics, sterilisation and modern marriage in the USA: The strange career of Paul Popenoe. Gender & History. 2001;13(2):298-327.

- Genetics | Oxford Academic. OUP Academic. Accessed August 4, 2024. https://academic.oup.com/genetics/genetics

- Davenport CB. Heredity in Relation to Eugenics. Holt; 1911:Pp. xi+, 298. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.29389

- Paul DB, Spencer HG. The hidden science of eugenics. Nature. 1995;374(6520):302-304.

- Benjamin L. The birth of American intelligence testing. Monitor on Psychology. 2009;40(1):20.

- Barkan E. Reevaluating progressive eugenics: Herbert Spencer Jennings and the 1924 immigration legislation. Journal of the History of Biology. Published online 1991:91-112.

- Popenoe P. Medical Eugenics. Journal of Heredity. 1923;14(2):64-64. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a102276

- Cook R. A year of German sterilization: 205 Eugenics Courts Yield 84,526 Sterilization Order in 1934. Journal of Heredity. 1935;26(12):485-489.

- Forbes A. Is eugenics dead? Journal of Heredity. Published online 1933:143-144.

- Ellinger T. On the breeding of Aryans: And Other Genetic Problems of War-time Germany. Journal of Heredity. 1942;33(4):141-143. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a105152

- Bird KA, Jackson JP, Winston AS. Confronting scientific racism in psychology: Lessons from evolutionary biology and genetics. American Psychologist. 2024;79(4):497-508. doi:10.1037/amp0001228

- Meloni M, Moll T, Issaka A, Kuzawa CW. A biosocial return to race? A cautionary view for the postgenomic era. American J Hum Biol. 2022;34(7):e23742. doi:10.1002/ajhb.23742

- A Dangerous Idea Eugenics, Genetics and the American Dream. bullfrogfilms; 2016. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/live/7kWC-M9BB1s?si=BVl3gwH74JI1Ggjm

- Sear R. Demography and the rise, apparent fall, and resurgence of eugenics. Population Studies. 2021;75(sup1):201-220. doi:10.1080/00324728.2021.2009013

- Gold M. Trump’s Long Fascination With Genes and Bloodlines Gets New Scrutiny. The New York Times (Digital Edition). Published online December 22, 2023.

JOSEPH (JERRY) LOCKHART, PhD, ABPP, is board certified in forensic psychology. Jerry has extensive experience in clinical and forensic psychology. He has published and presented on the reliability of forensic assessments, including bias reduction in clinical and forensic decision-making.

SATY SATYA-MURTI, MD, FAAN, is a clinical neurologist and health policy consultant. Following retirement, Saty has spent time researching cognitive biases, the social underpinnings of clinical medicine, Progressive Era medicine, and forensic sciences.