Eli Daniel Ehrenpreis

Skokie, Illinois, United States

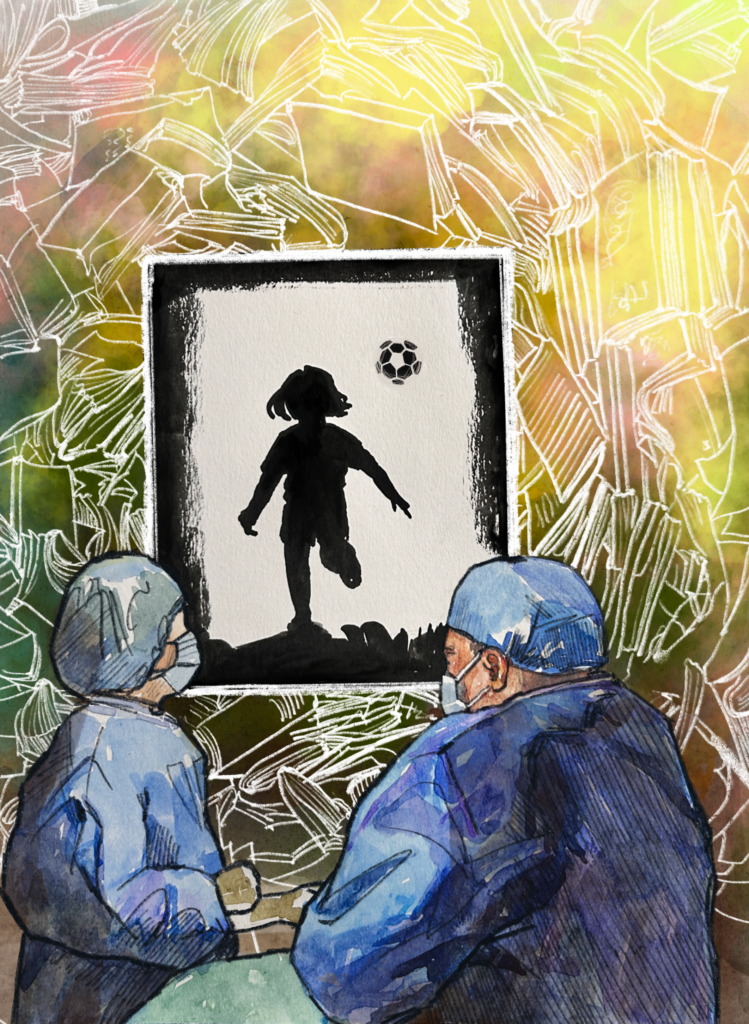

Of course, it was always assumed Morris Blechstein would take his final breaths sitting in his office, surrounded by scientific papers, studying his favorite medical literature to the end. But Morris made a surprise announcement. He was leaving because he always wanted to become a “good soccer dad” for the young daughter from his second marriage.

His plan painted an awkward picture. We imagined Morris hovering over his daughter’s coaches, berating them with the rule book, exhausting the refs with technicalities and obscure rules. Games would be delayed; soccer parents would be the unwilling audiences for long lectures. Eventually, he would be thrown out, much to his daughter’s embarrassment. We pictured him as a quiet spectator for the next game, then getting thrown out again a week or two later, and eventually receiving a lifetime ban. Would that bring him back to the university?

When Morris wasn’t with patients or in the hospital, you could find him at the copying machines in the library. The walls of his personal office were lined with filing cabinets filled with papers. Piles of loose articles were everywhere. A stainless-steel desk, just below a lonely window, was covered with heaps of paper. He read everything he copied and could spit the information back at you at any time. Years before my arrival, Morris’ office was condemned as a fire hazard, and he was forced to clean it up.

Morris published his groundbreaking gastroenterology atlas around the time I joined the faculty. The book transformed the practice of medicine. Before the Blechstein Atlas, endoscopy was learned by apprenticeship. Diagnosing what you saw through the eyepiece at the end of the scope was highly subjective and unreliable. It took him years to accumulate a massive paper file of thousands of pictures of abnormal intestinal structures, then match the microscopic slides from biopsies, and later collate the information with patient charts. Along the way, he also described several new diseases, and created eponyms still used today. To Morris, these accomplishments should have earned a promotion to full professor. He even tried appealing to the dean. But it never happened.

One day, Morris called me into the endoscopy suite. By then, the scopes had a video chip that captured a digital image projected on a screen. A group of trainees was watching him perform a colonoscopy. He questioned them about a collection of thin, yellowish-brown objects that appeared to be moving within the lumen of the colon. A resident suggested pinworms.

“Close,” Morris told them. “Pinworms are tiny and would be hard to see. Let me zoom in. Notice how the front part is long and narrow, moving back and forth, like a whip? These are whipworms, a scourge of mankind. In low-resource countries, whipworm infestations are sometimes diagnosed when an ultrasound shows a moving appendix. It’s called the ‘whipworm dance.’” That is an example of the mind of Morris. His vast knowledge of medicine was also on display at our weekly clinical conference. Cases were presented and he would talk, sometimes for an entire hour. The lecture room was always full.

Morris only gave three weeks’ notice that he was leaving and exited the night of his going away party in mid-April.

What a party it was, the night Morris Blechstein left the university forever!

The farewell celebration took place at the University Club, a spot where professors have enjoyed food and drink for more than one hundred years. I brought my cello and played a couple of movements from the Bach suites. Later, I was joined by a pianist and violinist on Mozart trios.

I was a little intoxicated by the end of the evening because my glass kept getting filled with red wine. I asked Morris his real reason for leaving.

“I think you know why, Eli. Just like me, the time will come when you will also step away.”

ELI DANIEL EHRENPREIS, MD, started life as a musician, then became a physician, educator, writer, and inventor. He stopped seeing patients due to disability. His latest book, The Mesentery in Health and Disease, was published by Springer International. His prose and poetry writing often focuses on his own experiences. He has three adult children, and lives with his wife Ana and two small dogs in Skokie, Illinois.

About the artist:

JR (JE RYONG) was born and raised in Seoul, South Korea and recently has been living in New Haven, Connecticut. She once envisioned herself in the quiet corridors of art museums, restoring timeless masterpieces. Now, she is trying to navigate the field of medicine as an incoming medical student while keeping her countless houseplants alive.

Leave a Reply