Richard de Grijs

Sydney, Australia

Heavy manual labor was part and parcel of the daily routine on eighteenth-century sailing ships. Although simple mechanical aids such as capstans (winches), blocks, and pulleys reduced some of the burden, shipboard life relied largely on enormous physical strain and exertion. Lifting heavy casks, or tubs of seawater for washing the decks, or hauling lines, sheets, halyards, braces, shrouds, and other ropes on pitching and rolling decks inevitably put significant pressure on one’s lower abdomen.

A flawed movement was easily made, and an abdominal rupture might occur. During the Age of Sail, such hernias were the most common occupational injury afflicting naval servicemen and merchant sailors alike. Sailors described the condition rather more graphically, as a “bursten belly”1 or a “burstened rupture.”2 In the Monty Python sketch “Up Your Pavement” (1974), ruptures were condemned by Michael Palin’s character, Rear Admiral Humphrey De Vere, Royal Navy Surgeon, as “the menace of long naval patrols.”

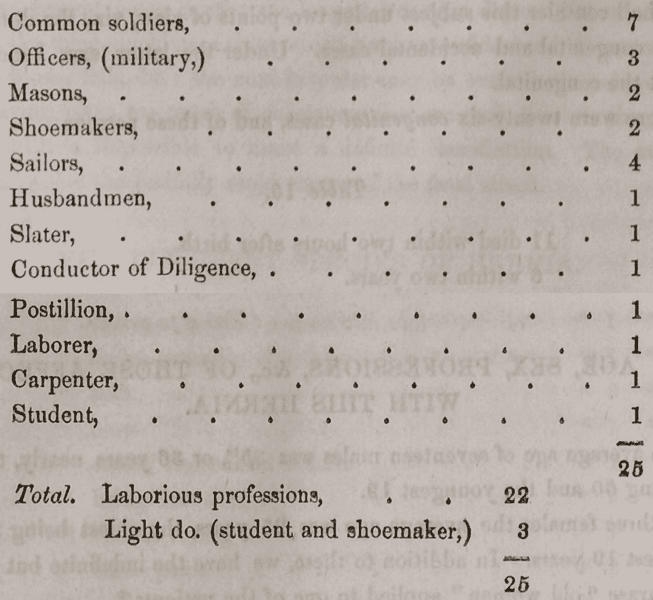

These injuries occurred frequently to workers in many professions that required heavy lifting and strenuous exertion—including coal miners, quarry laborers, stevedores, dock workers,3 engineers, and general laborers.4,5 This was clearly illustrated by the American physician Henry Ingersoll Bowditch (1808–1892) in a tabulated summary of all recorded hernia cases as of 1847 (Table 1), presented to the Boston Society for Medical Observation.6

Ruptures continued to plague sailors as long as heavy lifting and physical strain were routine aspects of shipboard life.7 As recently as 1999, the British Maritime and Coastguard Agency advised:

The abdominal cavity is a large enclosed space lined by a sheet of tissue. The abdominal wall muscles resist … changes of pressure … Increased pressure may force a protrusion of a portion of the lining tissue through a weak spot in the muscles … This forms a pouch and usually, sooner or later, a part of the abdominal contents will be pushed into the pouch. … The weakness may … be brought on by a chronic cough or strain. … [The patient] should be removed from heavy work. … If the hernia is painful, the patient should be put to bed. … Keep him in bed until he can be seen by a doctor at the next port.8

Most strain-induced ruptures are inguinal or groin hernias. They can be recognized as a soft, walnut-sized rounded swelling in the lower abdomen. Small ruptures usually do not affect one’s quality of life beyond minor discomfort or a dragging sensation. The protrusions can usually be pushed back into the abdominal cavity; such ruptures are known as “reducible hernias.” However, once a weak spot has been established, pushing the swelling back might not be viable in the longer term: the protrusion could recur and become an “irreducible hernia.”

Once a sailor had become “ruptured,” British Navy surgeon John Atkins (1685–1757) recommended “laying the patient on his back with his buttocks raised; and then … gently repressing [the swelling] with your hands.”9 He also advocated a change in diet, prescribing warm, nourishing meals of mutton, veal, lamb, or pullet while activities involving bowel exertion—walking, running, leaping, riding, coughing, sneezing, and inordinate laughter—“must be forbid.”10 Alternatively, patients should be relaxed by giving them a warm bath and, every eight hours, a grain of opium.11 If neither method worked, purging and bleeding were considered treatments of last resort. Once the patient had become limp from blood loss, the abdominal protrusion was to be rearranged manually. If all else failed, William Hunter (1718–1783), the Scottish anatomist and physician, suggested that

… making the patient stand on his head and throw his legs over the shoulders of a strong man who may give him a shake or two sometimes answers the [problem].12

Most hernias eventually require minor surgery. Although a routine operation today, in the eighteenth century herniotomy was rarely practiced. Instead, sufferers were fitted with a hernia “truss,” a padded belt designed to apply pressure to the weak abdominal area and prevent the swelling from deteriorating (Figure 1). Trusses contained a cloth, leather, or metal belt that was wrapped around the lower abdomen and kept in place by straps or springs. A second strap was fastened to the belt from the sailor’s back to his front, passing underneath the groin.13 Once a truss had been fitted, the British Sick and Hurt Board advised that patients “should not be obliged to hand or reef because the pressure they must meet with in that service would be very apt to force the intestines into the scrotum” again.14

Spurred by requests from captains in charge of pressed sailors, from 1744 metal trusses became the Royal Navy’s hernia treatment of choice.15 Eventually, the Navy Board distributed five trusses per one hundred men—one double truss and two each for the right and left sides—“ready to apply when sailors meet with accidents which occasion ruptures.”16 Between 1745 and 1747, the Royal Navy’s supplier delivered a grand total of 1,366 trusses.17 A few years later, between 1808 and 1815, the navy provided as many as 29,712 trusses across the fleet.18 And although navy trusses were “one size fits all,” they remained the most effective remedy for hernia treatment until surgery became the norm.

Mortality rates associated with inguinal hernias have historically been low. If a rupture was sustained during a voyage, sailors were usually assigned light duties. Nevertheless, they always ran the risk of the hernia growing, eventually preventing the men from working altogether and being sent back home as invalids. The debilitating consequences of ruptures were not always appreciated by those in charge, however, as we learn from a ruptured sailor in 1835, whose ship’s surgeon’s main consideration was to ensure that the man could work:

[Ship’s surgeon] Dr. James Brown [was summoned] to give an opinion on a seaman’s double rupture, … James confirmed that the man was indeed ruptured “on both sides—these I found properly secured by trusses.” He also “found that he had been labouring under inflammation of some of the viscera [intestines] …, but did not take any particular notice as Mr. Hill, Surgeon […], was well aware of this disease and had bled him for it—my opinion being only requested [to say] if he was fit for duty. … Dr. Brown … gave his professional opinion that the man “was not fit for work, in consequence of the state of his bowels—but fit as far as Hernia was concerned.”19

In serious cases, the swelling could cause intestinal blockage and evolve into a “strangulated hernia,” with the risk of a patient dying from gangrene increasing exponentially.20 Under such circumstances, the Maritime and Coastguard Agency explains,

… the contents of the hernia pouch may occasionally become trapped and compressed by the opening and it may be impossible to push them back into the abdomen. The circulation of blood to the contents may be cut off and if a portion of intestine has been trapped, intestinal obstruction may occur. This is known as a strangulated hernia and unless attempts to return the abdominal contents through the hernia weakness are successful, surgical operation will become urgently necessary. Get RADIO MEDICAL ADVICE.21

Although urgent hernia operations could be undertaken on board if the condition was life-threatening,22 prior to the nineteenth century—before the routine application of anesthesia—surgery was considered hazardous. Herniotomy was a last resort, given the risk of infection and the nigh inevitability of death:23,24 “recurrence was frequent and mortality was high.”25 Eighteenth-century civilian physicians hence considered hernias chronic and inoperable.26 The naval establishment, however, was loath to human wastage, specifically as regards their valuable servicemen.

Ruptures were particularly prevalent among pressed sailors,27 who were usually recruited from other manual labor trades. In the early nineteenth century, as many as one in seven British sailors may have suffered from hernias. For the general population, contemporary estimates suggest that 10 percent may have been ruptured28; today’s figures are closer to one in twenty. Sailors’ exposure to heavy physical exertion was most acutely felt on merchant, fishing, and whaling vessels, which often operated on the basis of minimal crewing to yield maximum profits.29 In the Royal Navy, on the other hand, ships were adequately crewed, but crew recruitment was subject to stringent assessment. The Directions for the Examination of Officers, Men, and Boys for Admission into the Royal Navy and Marines (1879) explicitly state:

When a Medical Officer is directed to examine any person for admission into the Naval Service, or into the Royal Marines, … The abdomen is next to be examined for the purpose of detecting any enlargement or disease of the contained viscera, or predisposition to hernia from whatever cause.

…

Persons of whatever class, or age, who are found to be labouring under any of the undermentioned physical defects or infirmities, are to be considered unfit for Her Majesty’s Service:

…

9. Swelling or distension of the abdomen, …, Rupture, weakness or distension of the abdominal rings; ...30

Navy ratings (recruits) who developed large or recurrent hernias were discharged as unfit for duty. Admiral George Brydges Rodney (1718–1792) was particularly outspoken on the occurrence of hernias as a nuisance, writing to the Admiralty that his men were “extremely liable from the various exertions of their duty to the disorder called ruptures,” and that “these men [were] discharged … because the trusses now sent on board ships hardly ever prove[d] of the smallest benefit.”31 Nevertheless, navy sailors were markedly less affected by hernias than the country’s general population,32 possibly because of their stringent selection process. Yet, despite surgeons’ best efforts, hernias remained a major naval health hazard while heavy physical strain continued to dominate shipboard life.

References

- e.g., Chipperfield, WN. 1862. “Notes upon Certain Surgical Applications, and upon Some Minor Points in Surgery.” The Madras Quarterly Journal of Medical Science, 5, (1862): 238–259; Rice, GW. A Fatal Herniotomy and the Medical Libel Case of 1886: Dr Nedwill’s Pursuit of Dr McBean Stewart. (Christchurch, New Zealand: Hawthorne Press, 2021), 7.

- Reid, P. A Boston Schooner in the Royal Navy, 1768–1772: Commerce and Conflict in Maritime British America. (Martlesham, UK: Boydell and Brewer, 2023), 205.

- Banks, WM. “On the Radical Cure of Hernia, by Removal of the Sac and Stitching Together the Pillars of the Ring. The British Medical Journal, 2, (1882): 985–988.

- Heaton, G. “Radical Cure of Hernia (Case IV).” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 31, (1844): 260–262.

- Parker, R. “Discussion on the Radical Cure of Hernia. The British Medical Journal, 2, (1893): 1037–1044.

- Bowditch, HI. “Peculiar case of Diaphragmatic Hernia, … (concluded).” Buffalo Medical Journal and Monthly Review, 9, (1853): 65–99 (Table 14, pp. 79–80).

- Parker, op. cit.

- Maritime and Coastguard Agency (Great Britain). The Ship Captain’s Medical Guide, 2nd ed. (London: The Stationary Office, 1999): 148.

- Atkins, J. The Navy-surgeon: Or, a Practical System of Surgery. (London: Caesar Ward and Richard Chandler, 1734).

- Convertito, C. 2011. “The Health of British Seamen in the West Indies, 1770–1806.” (PhD Thesis, University of Exeter (UK), 2011): 88.

- Goddard, JC. “Genitourinary Medicine and Surgery in Nelson’s Navy.” Postgraduate Medical Journal, 81, (2005): 413–418.

- Quoted by Mills, PR. 2007. “Privates on Parade: Soldiers, Medicine and the Treatment of Inguinal Hernias in Georgian England.” In: Hudson, GL (ed.), British Military and Naval Medicine, 1600–1830. (Leiden: Brill, 2007): 149–182: see p. 159.

- Wells, TS. The Scale of Medicines with which Merchant Vessels are to be Furnished, By command of the Privy Council for Trade. (London: John Churchill, 1861); Convertito, op. cit., 116.

- Quoted by Mills, op. cit., 162.

- Convertito, op. cit., 116.

- National Maritime Museum (UK), 1 March 1744. Letter from the Admiralty to the Sick and Hurt Board. ADM/E/11.

- Mills, op. cit., 161.

- Thomas, E. John Paul Jones. Sailor, Hero, Father of the American Navy. (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2010).

- Druett, J. Rough Medicine: Surgeons at Sea in the Age of Sail. (New York: Routledge, 2001): 192. For a similar attitude, see also the case study of “Morris vs. United States” on p. 792 of Gionis, TA., “Paradox on the High Seas: Evasive Standards of Medical Care – Duty Without Standards of Care; A Call for the International Regulation of Maritime Healthcare Aboard Ships.” John Marshall Law Review, 34, (2001): 751–801.

- Rice, op. cit., 8.

- Maritime and Coastguard Agency (Great Britain), op. cit., 148.

- Hamerton, JR. Correspondence. The British Medical Journal, 2, (1935): 1025.

- Rice, op. cit., 8.

- Van de Burgh, CF. The mariner’s medical guide. Comprising various diseases, with their general symptoms and most appropriate treatment, clearly and plainly stated, suitable to any capacity; also, the different causes and preventives of each depending upon change of climate. (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1819).

- Ewing, EG. “History of the Treatment of Inguinal Hernia.” MD Thesis, (University of Nebraska, 1935): 19.

- Mills, op. cit.; Convertito, op. cit., 88.

- Convertito, op. cit., 116.

- Hilaire-Pérez, L. and Rabier, C. “Self-Machinery? Steel Trusses and the Management of Ruptures in Eighteenth-Century Europe.” Technology and Culture, 54, (2013): 460–502.

- Thomas, op. cit.

- Navy List, 1879. Article 4: Directions for the Examination of Officers, Men, and Boys for Admission into the Royal Navy and Marines. Addenda to the Queen’s Regulations, p. 132. https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~pbtyc/genealogy/Navy_List_1879/Medicals_Entry.html [accessed January 2, 2024].

- Rodney, GB. 7 December 1781. Letter to the Admiralty, ADM 1/314. Kew: UK National Archives.

- Stephens, HER. “Abdominal Hernia in the Royal Navy.” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine (War Section), 22, (1927): 493–501.

RICHARD DE GRIJS, PhD, is an astrophysicist and an award-winning science historian at Macquarie University (Sydney, Australia). He has a keen interest in the history of maritime navigation. Richard is a volunteer guide on Captain Cook’s (replica) H.M. Bark Endeavour at the Australian National Maritime Museum. He also regularly sails on the Museum’s replica Dutch East India Company vessel, Duyfken.