Nicolas Roberto Robles

Badajoz, Spain

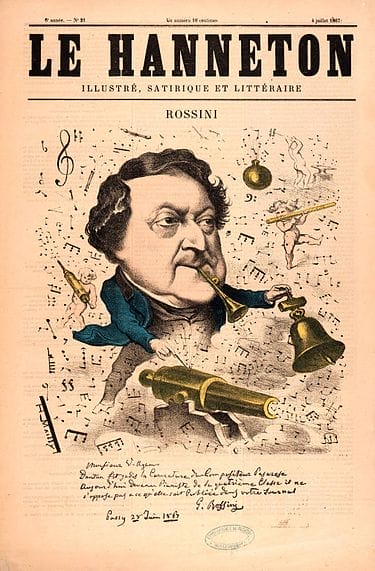

Born in a family of musicians in Pesaro, Italy, Gioachino Rossini1 displayed inordinate talent from an early age, encouraged by his mother Anna, a notable singer, so that by the age of six, he was already playing the triangle in his father’s musical group. In 1799, Rossini’s father was sent to prison for one year for supporting the French Revolution. His mother then took him to Bologna, where she was singing in various theaters. Young Gioachino Rossini entered Bologna’s Philharmonic School and composed his first opera, Demetrio e Polibio, at the age of fourteen subsequently becoming increasingly successful. Between 1815 and 1823 he lived in Naples, where he produced most of his operas, including his most famous masterpiece, The Barber of Seville.2

After writing 38 operas in Italy, Rossini moved to Paris in 1824, and after producing one more opera, dedicated himself to gastronomy, declaring “I know of no more admirable occupation than eating.”3 He rapidly became morbidly obese, as shown in the photos. Richard Wagner, with his caustic sense of humor, said: “He was filled no longer by music which had left him long ago but rather by mortadella”. Several “haute cuisine” dishes were named after Rossini, including “Crema alla Rossini”, “Frittata alla Rossini”, and “Tournedos Rossini”, all rich dishes prepared with truffles and foie gras.4 Of these, Tournedos Rossini is the most famous, not created by him but merely named after Rossini because his butler was made to “tourner le dos” (turn his back) on the diners so as to “hide the secret of the final touches of this dish created by a famous chef, Marie-Antoine Carême, with Rossini’s supervision.”3 Adolphe Dugléré or Auguste Escoffier (famous nineteenth-century French “chefs de cuisine”) have been also suggested as the possible authors of this recipe.5

Rossini contracted chronic gonorrhea around 1830, apparently from a prostitute. He suffered from gonococcal cystitis, which was very painful, and from urethral stricture, for which he was frequently catheterized and washed with sweet almonds, mallow, flower of sulfur and cream of tartar. He also resorted to stays in spas, diets and “magnetic cures.” Finally, he turned to Dr. Jean Civiale, a specialist at the Necker Hospital in Paris, who recommended dilations with Béniqué tin bougies (urethral dilators), which apparently were effective in reducing his symptoms. In the period of convalescence Rossini wrote a series of 180 vocal and instrumental compositions entitled Pechés de viellesse (Sins of old age). Some have such rare titles as “Prélude convulsivf”, “Mon prélude hygiénique du matin”, or “Valse torturée”. Rossini was so grateful to the treatment with the dilatations that it is said that he even had a Beniqué bougie among the objects that decorated his salon and to which he often referred to as the instrument to which he owed his happiness.6 In 1868, he developed a rectal carcinoma and was operated on under chloroform by Auguste Nélaton, personal physician of emperor Napoleon III. He died on November 13, 1868, and was temporarily buried at Père-Lachaise. In 1887 his widow Olympe persuaded the French government to allow his remains to be transported to Italy, where his final resting place is in the church of Santa Croce in Florence.

References

- “Gioachino Rossini.” Famous Composers. https://www.famouscomposers.net/gioachino-rossini.

- Nicholas Till. Rossini: His Life and Times (The Illustrated Lives of the Great Composers). London: Omnibus Press, 1987.

- Tom Huizenga. “Composers in the kitchen: Gioachino Rossini’s Haute Cuisine.” NPR Deceptive Cadence, November 25, 2010. https://www.npr.org/sections/deceptivecadence/2010/11/24/131568241/composers-in-the-kitchen-gioachino-rossini-s-haute-cuisine.

- Note 21 on “Gioachino Rossini,” Wikipedia, from Gaia Servadio, Rossini, London: Constable, 2003, p. 12. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gioachino_Rossini#cite_note-100.

- Ira Braus. Classical Cooks: A Gastrohistory of Western Music. 2006. Bloomington, IN: Xlibris Corp, 2006.

- Joseph Lewis. What killed the great and not so great composers? Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2010.

NICOLAS ROBERTO ROBLES is professor of Nephrology at the University of Extremadura (Badajoz) and member of the Academy of Medicine of Extremadura.