Eelco Wijdicks

Rochester, Minnesota, United States

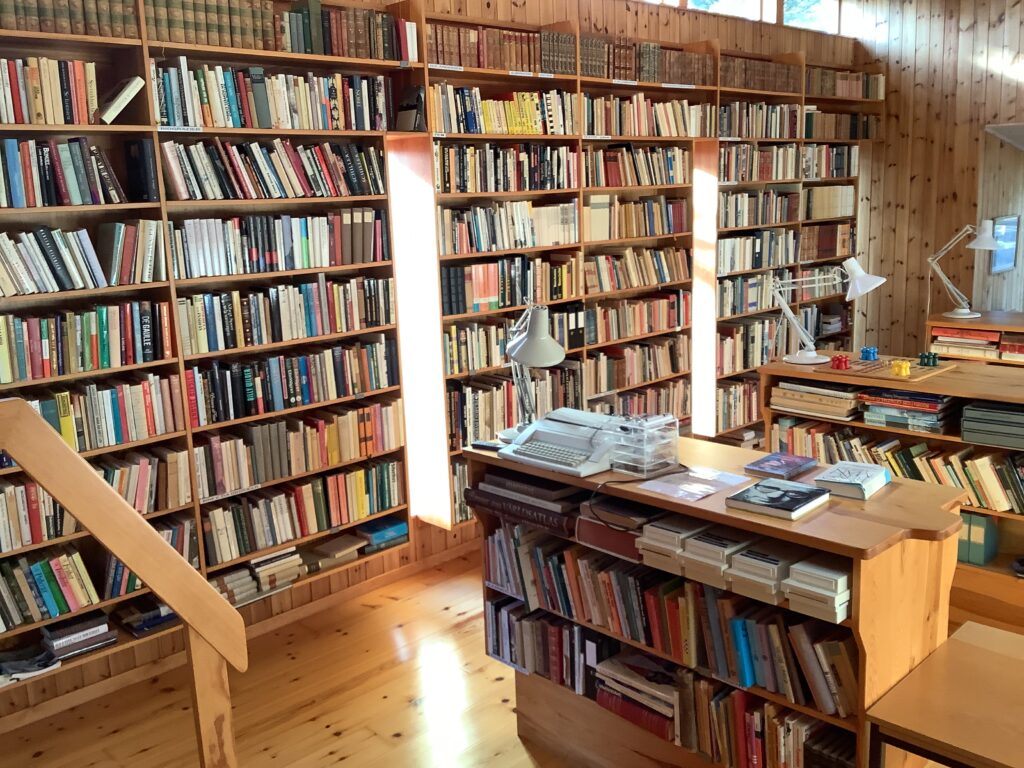

Ingmar Bergman’s films are existentialist cinema. Cineastes revere his work, despite its allegedly problematic treatment of women and his unapologetically misogynistic and sexist protagonists. His personal life was just as complicated as his films; he married five times and had problematic, intense working relationships with his actors, including sexual affairs. His personal possessions, including reading material, may offer clues to his sources of inspiration. The curators of his home in Hammars, Fårö Island, where Bergman moved in 1967 and lived until his death in 2007 at the age of eighty-nine, have made available the catalog of his extraordinary library. In addition to books on geography, gardening, art, architecture, ballet, theater, photography, and film, it includes a collection of books on psychology and psychiatry separately shelved under Psykolgi (Figure).

A book by Sigmund Freud (Sigmund Freud Fallstudier) may have inspired Wild Strawberries as well as other Bergman films. Freud wrote extensively in Die Traumdeutung on the so-called examination dream: “Everyone who has received his certificate of matriculation after passing his final examination at school complains of the persistence with which he is plagued by anxiety dreams in which he has failed or must go through his course again…These are the ineradicable memories of the punishments we suffered as children.” Wild Strawberries (1957) shows a key dream sequence where the protagonist, Dr. Isak Borg (Victor Sjöström), is unable to perform a simple medical test or read the letters on the blackboard. The examiners pronounce him “incompetent.” Dreams of failing medical exams are common among physicians, but these nightmares also occur in artists, from concert performers to filmmakers. In a Time magazine interview,2 Woody Allen said that Bergman had similar dreams; for instance, showing up on the set and not remembering where to place his camera.

Carl Jung’s classic work Människan och hennes symboler (Man and his Symbols, 1968) is also in Bergman’s collection. This book posits that events revealed to us in dreams are symbolic images. For Jungians, the unconscious mind sees patterns that the conscious mind does not see. Bergman’s Wild Strawberries nightmares were full of symbolic images (such as a clock with no hands and empty streets), but its true meaning in the film has always remained elusive and surrealistic.

The library also includes the 1973 book Anatomie der menschlichen Destruktivität (The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, 1973) by the psychoanalyst Erich Fromm. (Parenthetically, Liv Uhlmann plays Anna Fromm in Passion of Anna.)This work is of interest because Fromm presents a new type of malignant character, the “necrophilous,” who is driven by a strong urge for unmitigated destruction. We may speculate whether this inspired Bergman to create the scenes from The Life of Marionettes (1980) in which the protagonist rapes and murders a prostitute.

The collection contains books by Kazimierz Dąbrowski, Psychoneurosis Is Not an Illness (1972) and The Dynamics of Concepts (1973). Dąbrowski was a Polish psychologist, psychiatrist, and physician best known for his theory of “positive disintegration” as a mechanism in personality development. In this theory, he postulates that personality development progresses through accumulated difficult experiences. “Disintegration” refers to the removal of prior attitudes. The resulting shift, if there is one, may be positive when the process has created a personality with the increased capacity to incorporate experiences and gain new perspectives.

Bergman also read Karen Horney’s classic 1968 book Self-Analysis. She was a German psychoanalyst who immigrated to the United States during her later career. Her theories questioned traditional Freudian views and she originated the academic field of feminist psychology. Horney is a neo-Freudian member of “the cultural school,” which also includes Eric Fromm, Harry Stack Sullivan, Clara Thompson, and Abraham Kardiner. Horney felt that men envied a woman’s ability to bear children. The degree to which men strive to succeed may be merely a substitute for the fact they cannot carry, bear, and nurture children. However, in Self-Analysis Horney considers the necessity of self-analysis and attempts to interpret the driving forces in neuroses.

Johan Culberg’s books are Creating Crisis (1992) and The Psychic Trauma: About Crisis Theory and Crisis Psychotherapy (1971). These publications introduced the psychiatric crisis as an entity and inspired other psychiatrists to introduce crisis psychotherapy in psychiatric clinics. Culberg felt that the patient should not repress this crisis but rather heal while going through the crisis with psychiatrists and psychologists in support.

Celia Green is a philosopher and psychologist best known for her pioneering research on perceptual phenomena such as lucid dreams and out-of-body experiences. The Decline and Fall of Science (1976) concerns the nature of society, which Green claims holds back its members from achieving their potential. The second part of the book consists of reports of paranormal events collected by Green’s Institute for Psychophysical Research including lucid dreams, apparitions, and psychokinesis.

Two books by the anti-psychiatrist RD Laing are included: Self and Others and Sanity and Madness in the Family written with Aaron Esterson. Bergman (and fellow filmmakers, including Ward, Litvak, Wiseman, and Fuller) were interested in the civil liberties argument, which postulates that people are committed for convenience.

Clarence Crawford, a psychiatrist trained as a psychoanalyst with a focus on Freudian group psychotherapy and family therapy at Svenska Psychoanalytical Institute, was a personal friend of Bergman’s. He authored books on general topics: Människan är en berättelse (Man is a Story, 1994), Barndomens återkomst (The Return of Childhood, 1994), and others, but these books postdated Bergman’s major films.

Oluf Martensen-Larsen with Kirsten Sørrigwrote Forstå dit ophav og bliv fri (Understand Your Origin and Be Free). Martensen-Larsen was a psychiatrist best known for developing apomorphine because he thought aversion therapy against alcoholism was flawed. The book, based on his material from almost forty years of psychologically oriented genealogical research, stated that the location of parents, grandparents, and even great-grandparents can influence development and the partners, friends, education, and professions we choose, just as parents’ perceptions of their own parents can come to influence the children.

Mihaly Robert Csikszentmihalyi wrote Flow Den optimala upplevlespsyklog (The Psychology of Optimal Experience). Csíkszentmihályi was a Hungarian American psychologist who proposed that people are happiest when they are in a state of flow—a state of concentration or complete absorption with the activity at hand. This creates a feeling of great, engagement, fulfillment, and skill during which other concerns diminish or temporarily disappear.

Finally, a 1970 book by Arthur Janov, Primalskriket (Primal Scream). Janov was popular in Sweden, and his books “flew off the shelves” in Swedish bookstores. Janov asserted that repressed pain from the childhood trauma of lacking parental love resulted in neurosis, physical disorders, and an inability to have authentic feelings.

Notably absent from his library is the Swedish translation of Finnish philosopher Eino Kaila’s Personoonalisuus (1934), proclaiming that man must live according to his needs, which Bergman mentioned as influential in his screenplay writing over thirty years later.3

Some of these books contain discredited theories and dubious treatments, and we can only speculate how his surviving library (as well as any discarded works) influenced his plays and films. Bergman’s thematic films did not emerge from a vacuum. Bergman used assaults on identity and other confrontations in his films, and he could have found inspiration in each of these books. There is no common thread in the books in his library, and we do not know whether he purchased them or received them as gifts. Many fall into the category of “self-help” books.

Childhood experiences (real or fantasized) are also resources for filmmakers and writers, and Bergman grew up with fears of punishment and humiliation. The relationship to one’s own childhood, a search for meaning, faith, and family relationships have all been major themes in his work. However, Bergman likely wove the imaginative and fictive into his life story. Bergman received treatment for depression following the death of his wife Ingrid in 1995. In the documentary Bergman Island, filmed when he was eighty-five, he listed his demons: the worst was the demon of disaster (he had been highly prepared for that day), followed by fear (animals, “several kinds of people,” and “large crowds”), rage (“irascible”), and grudges. The demon he said he did not have, which he was “profoundly grateful” to have avoided, is the demon of nothingness (“when my creativity of my imagination abandons me” and “things go totally silent, get totally empty and there is nothing there”). We should not discount the possibility that the books in his library may have been used to manage his wistfulness, as well as for self-analysis and understanding of his own failings.

References

- Wijdicks E. The bedside manners of Ingmar Bergman’s celluloid physicians. Hektoen International, 2020. https://hekint.org/2020/08/13/the-bedside-manners-of-ingmar-bergmans-celluloid-physicians/.

- Corliss R. Woody Allen on Ingmar Bergman. TIME. New York: TIME USA, LLC; 2007.

- Bergman I. Introduction. Four Screenplays of Ingmar Bergman Smiles of a Summer Night, The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries & The Magician. 1st ed. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1960: 330.

EELCO WIJDICKS, MD, PhD, is a Professor of Neurology and History of Medicine at Mayo Clinic with subspecialty interest in Neurointensive Care and the author of Cinema MD: A History of Medicine on Screen (Oxford University Press 2020), and Neurocinema: The Sequel (CRC Press, 2022). This essay is an extract from his upcoming work, Frames of Mind: The History of Neuropsychiatry on Screen (Oxford University Press, 2024).

FUNDING STATEMENT: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Leave a Reply