|

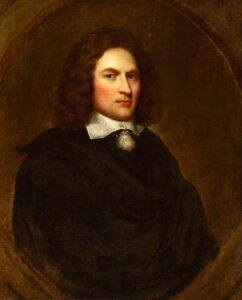

| Richard Wiseman. Photo by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. Hunterian Museum, London. Via ArtUK. |

Richard Wiseman lived in the turbulent seventeenth century that devastated Western Europe by its internecine conflicts. Germany was torn apart by the Thirty Years War, France by the rebellion known as the Fronde, and England by the Civil War that culminated in the execution of its monarch in 1649. In 1665 London was devastated by an outbreak of the plague that killed 1,000 persons each week and some 100,000 over its entire course. It ended a year later with the famous Great Fire. The century is also remembered for its great literary figures John Milton and John Locke, the scientists Isaac Newton and Robert Boyle, William Harvey who described the circulation of the blood, and Thomas Sydenham who reigned supreme as the greatest practicing physician of his time. And it was to him that Richard Wiseman has been compared as the “Father of English Surgery.”

Nothing is known about Wiseman’s early life except that he was born around 1622 and may have been the illegitimate son of a nobleman. Apprenticed to a barber-surgeon at age fifteen, he learned his craft largely in the navy and on the battlefield. He first served in the Dutch navy, and then his life became inextricably linked with that of Prince Charles, the future King Charles II. Serving as his surgeon in France, Holland, and Scotland (1646–1650), he took part in several battles and was taken prisoner in 1650 by the forces of Oliver Cromwell. Paroled and released, he spent the ensuing decade mainly in London. Several times he was arrested—apparently for involvement with royalist causes—yet was able to set up a successful surgical practice near the Old Bailey. For a brief time in the late 1650s, he worked as naval surgeon for Spain in the West Indies.

In 1660, within a few days of the Restoration, he was appointed surgeon extraordinary to King Charles II, rising to positions of increasing prestige, and eventually being elected Master of the Company of Barber- Surgeons. He practiced surgery successfully even though increasingly troubled by ill health, which included shortness of breath and coughing up blood (presumably from tuberculosis) even while operating. He promoted cleanliness and proper wound care to reduce post-operative infections. He devised new procedures to suture intestinal wounds and introduced the use of silk threads for stitching wounds. By virtue of the many dissections he performed during his life, he also became a skilled anatomist.

In 1672 Wiseman wrote A Treatis of Wounds, expanded in 1676 to Several Chirurgicall Treatises. He covered surgical techniques, wounds, fractures, tumors, gunshot wounds, and syphilis. He also relates the many and varied clinical situations he was called upon to treat: a man who developed pain above his left hip after standing in the cold to watch a play, one who developed pain in his upper jaw after cracking open an apricot stone, one impaled in the wrist while also trying to watch a play, and one thrown off his frightened horse when someone emptied a chamber pot out of the window.

Though well-educated and familiar with Latin and with the works of Hippocrates, Galen, and Celsus, Wiseman emphasized that he based his book on his own experiences and observations in the “Armies, Navies and Cities, not in Universities.” He explained he was “not much conversant in Books, his constant employment leaving little leisure from his profession.” His surgical work was published posthumously in 1676 after he died suddenly at Bath. He is remembered as the greatest surgeon of his generation.

Further reading

- Review: Richard Wiseman, Surgeon and Sergeant-Surgeon to Charles II by T. Longmore. BMJ Jan 23, 1892;1:176.

- Alan DeForest Smith. Richard Wiseman: His Contributions to English Surgery. Bull NY Academy of Medicine March 1970;46(3):167.

- Michael McVaugh. Richard Wiseman and the Medical Practitioners of Restoration London. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences April 2007;62(2):125.

- Richard Wiseman as a naval surgeon. BMJ Sept 29, 1917:431.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Leave a Reply