Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“Maladie dévoreuse de beauté et de vie”1

(“An illness devouring both beauty and life”)

– Edmond Kaiser, founder of the humanitarian organization Fondation Sentinelle

|

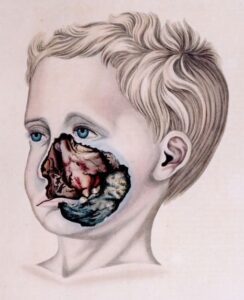

| Noma (gangrenous stomatitis). Illustration by Robert Froriep, 1836. © Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Charité, Barbara Herrenkind. Via Wikimedia. Public domain. |

Noma (also called necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis, gangrenous stomatitis, or cancrum oris), is a disease of extreme poverty. It progresses rapidly and is often fatal. Victims of this infection are usually between two and six years old and live in poor, tropical regions, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, but also in Asia and South America. Noma produces ulcers of the mucous membranes of the mouth, and rapidly leads to painful and deforming tissue loss, including necrosis of the bones of the face. It is infectious, but patients are not contagious. The first sign of noma is a necrotizing gingivitis. The gums are inflamed and bleed spontaneously. Fever may be present. Next, swelling of the lips and cheeks begins, and ulcers form on the oral mucosa. The patient has pain, fever, and swollen lymph nodes. The condition progresses to gangrene of the cheeks, lips, and oral and nasal mucosa. Eating is difficult, and scarring occurs in areas of tissue loss.2 The perineum and vulva may also be involved.3 Hence, the word “noma” comes from the Greek numein, “to devour.”

The condition has been known since antiquity. It was seen in Europe and North America in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Noma was found in the Nazi concentration camps Auschwitz-Birkenau and Bergen-Belsen, as well as in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps and the Netherlands during the “Hunger Winter” of 1944–45.4

Risk factors include the sine qua non of protein-calorie malnutrition (which decreases production of immunoglobulin A, or IgA—needed for mucosal immunity), poor oral hygiene and recent illness, especially measles, but also malaria or severe diarrhea. Dietary deficiency of vitamins A, B, and C and proximity to livestock also predispose one to noma, as well as not having been breastfed or early weaning, a compromised immune system (especially by HIV infection), and cystic fibrosis.5-7

Without treatment, 73–95 percent of patients die, usually from septicemia following the gangrenous stage.8 Current treatment consists of a penicillin-derived antibiotic, plus the antimicrobials gentamicin and metronidazole. Antiseptic mouthwashes are also used. In Africa, treatment has reduced the death rate to anywhere from 0 to 30 percent depending on region.9 Tissue loss is irreversible and requires multi-stage maxillo-facial and plastic reconstruction.

Noma is a polymicrobial infection, often attributed to the combination of Fusobacterium necrophorum and Prevotella intermedia bacteria, in the presence of non-syphilitic treponemata, Staphylococcus aureus, or streptococci. Cytomegalovirus, a herpes virus, has also been suspected of being the infectious agent.10,11

The direct costs of treating and rehabilitating patients with noma have been estimated at USD $30 million per year in Burkina Faso, $31 million per year in Niger. Costs include antibiotic treatment, surgeries, hospitalizations, psychological and social assistance, education, and vocational training.12 The social stigma around noma survivors is enormous, especially when local beliefs include that the disease is contagious, produced by witchcraft, or a punishment from God. There is one dedicated noma hospital in Nigeria.13

“The continued existence of noma is evidence that the most vulnerable children lack the basic right to food.”14

References

- Denise Baratti-Mayer et al. “Noma: An ‘infectious’ disease of unknown etiology.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 3, July 2003.

- Cyril Enwonwu. “Noma: A neglected scourge of children in sub-Saharan Africa.” Bull World Health Organ 73(4), 1995.

- Joseph Morelli. “Disorders of the mucous membranes.” In Robert Kleigman et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18th ed, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

- Elise Farley et al. “Noma (cancrum oris): A scoping literature review of a neglected disease (1843 to 2021).” PLoS Negl Trop Dis 15(2), 2021.

- Wubishet Gezimu et al. “Noma – a neglected disease of malnutrition and poor oral hygiene: A minireview,” SAGE Openmed 10, 2022.

- Farley et al, “Literature review.”

- Enwonwu, “A neglected scourge.”

- George Weaver and Ruth Tunnicliff. “Noma: (gangrenous stomatitis, water cancer, scorbutic cancer, gangrene of the mouth).” Journal of Infectious Diseases 4(1), 1907.

- Baratti-Mayer et al, “An ‘infectious’ disease.”

- Baratti-Mayer et al, “An ‘infectious’ disease.”

- Enwonwu, “A neglected scourge.”

- Emmanuel Mpinga et al. “Economic and social costs of noma: Design and application of an estimation model to Niger and Burkina Faso.” Trop Med Infect Dis 7(7), 2022.

- Enwonwu, “A neglected scourge.”

- Margaret Srour et al. “Noma: Overview of a neglected disease and human rights violation.” Am J Trop Med Hyg 96(2), 2017.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Summer 2023 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply