Kingston Bridges

London, United Kingdom

|

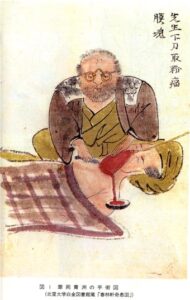

| Hanaoka performing the first operation with tsūsensan. University Hospital Medical Information Network Center. |

Since time immemorial, humans have sought to alleviate illness and suffering through surgical interventions. Amputations with improvised tools took place in the Upper Paleolithic period over 30,000 years ago, and skeletal evidence of trephining has been found in excavations on several continents. Throughout the centuries, as an understanding of the human body developed, the reality of the pain of surgery hindered medical progress. Before the advent of modern anesthesia, surgery was a terrifying experience and had to be performed with almost reckless speed. To mitigate pain, surgeons in Europe began testing the effectiveness of substances such as alcohol, coca, and opioids, but results were limited—until on March 30, 1842, Crawford W. Long administered what is known as the first successful general anesthetic, using diethyl ether. Yet another date in the history of anesthesia predates this: in 1804, Japanese doctor Hanaoka Seishū administered what is arguably one of the world’s first general anesthetics, allowing him to perform operations that until then would have been impossible.

Hanaoka Seishū (1760–1835) descended from a family of physicians in the Wakayama Prefecture of Japan during the Edo period (1603–1867). Serving as his father’s apprentice placed him on the path to a successful medical career. Relocating to the city of Kyoto at the age of twenty-two, he studied with Dr. Nangai Yoshimasu, a distinguished Chinese medical practitioner. He learned Chinese herbal medicine and created his own anesthetic formula, which he called “tsūsensan” (soo-sen-sahn). Tsūsensan was a mixture of several botanical substances such as datura (Datura metel), which contains the anticholinergic alkaloids scopolamine and atropine; these alkaloids also have a sedative effect, causing amnesia and making them useful as anesthetics. The mixture also contained angel’s trumpet (Brugmansia suaveolens) from the same biological family as datura and containing similar alkaloids, as well as Japanese monkswood (Aconitum carmichaelii) that possessed analgesic aconitine. Tsūsensan was prepared by processing and combining these botanical ingredients, extracting their active components, and dissolving them in alcohol to create the final anesthetic formulation. The quantities and ratios of the ingredients likely played a crucial role in determining the potency and safety of tsūsensan as an anesthetic.

What many believe made tsūsensan a success where other remedies had failed was Hanaoka’s incorporation of a variety of regionally different disciplines of medicine. Among them were Dutch surgical techniques carried to Japanese students through the policy of Rangaku, where scientific knowledge was traded between the two nations during this period. Hanaoka, while studying in Kyoto, had learned the latest western techniques of surgery obtained from Holland, which rivaled speedy English surgeons such as John William Hunter (1728–1793). Hanaoka experimented on dogs with various formulas over several decades until he achieved a formulation that he could administer to humans. He included his wife in his first human trials, reporting her to be in a state of “desensitized paralysis” for as long as six to twenty-four hours before waking up. Patients undergoing surgery with tsūsensan experienced minimal discomfort. In 1804, he applied his knowledge of Chinese and Dutch medicine, as well as tsūsensan, in performing a mastectomy upon a sixty-year-old patient, which is believed to be the first successful use of a general anesthetic.

|

| Botanical components of tsūsensan (click to view). Illustration from International Museum of Surgical Science, Chicago, IL. |

While tsūsensan proved effective in eliminating the pain of surgery, this presented certain challenges and ethical concerns. The complex preparation of the anesthetic made it difficult to administer precise dosages, leading to potential toxic reactions. This led Hanaoka, in his further teachings in Japan, to insist that his students kept his formula strictly confidential. He did this to keep his methods out of the hands of practitioners who would be unaware of its potentially dangerous properties. This secrecy, as well as the isolationist nature of pre-Meiji restoration Japan, meant that this valuable discovery would remain in Japan for decades.

By way of contrast, at about the same time, Abigail Adams Smith, daughter of the second US president John Adams, underwent mastectomy without anesthesia. She suffered agonizing pain during half an hour of surgery and another hour to dress the wound. It is difficult to compare the outcomes of Hanaoka’s patients with those of other surgeons, as their clinical course after procedures were not recorded. We can be sure, however, that Hanaoka’s patients experienced no pain during surgery, while others around the world were not so lucky.

Hanaoka laid the foundation for modern anesthesia in Japan. His discovery allowed him to perform over 150 procedures for breast cancer, as well as others that were previously too painful to perform, such as anovaginal fistula repair or lithotomy. The use of tsūsensan is now recognized as one of the earliest instances of general anesthesia, cementing Hanaoka’s legacy as a medical pioneer.

References

- “Stone Age Surgery: Earliest Evidence of Amputation Found,” The University of Sydney, 2023, sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2022/09/08/stone-age-surgery-earliest-evidence-of-amputation-found-archaeology.html.

- Andrea Estrada, “Ancient Cranial Surgery,” The Current, Dec 19, 2013, news.ucsb.edu/2013/013852/ancient-cranial-surgery.

- Roger Thomas, “Crawford W. Long’s Discovery of Anesthetic Ether: Mesmerism, Delayed Publication, and the Historical Record,” The University of Georgia, 2003, uga.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/LongEther16March2016.pdf.

- “The Art of Anaesthesia,” London Science Museum, 2018, sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects-and-stories/medicine/art-anaesthesia.

- Drew Kotler, Hitoshi Hirose, Charles Yeo, Scott Cowan, “Dr. Seishu Hanaoka (1760-1835): surgeon, pharmacist, and anesthesiologist,” Thomas Jefferson University, 2014, jefferson.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=gibbonsocietyprofiles.

- Tomio Ogata, “Seishu Hanaoka and His Anaesthesiology and Surgery,” 1973, https://associationofanaesthetists-publications.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2044.1973.tb00549.x.

- “Made for This Moment | Anesthesia, Pain Management & Surgery,” American Society of Anesthesiologists, 2023, asahq.org/madeforthismoment/anesthesia-101/types-of-anesthesia/.

- “John Hunter (1728-1793),” National Records of Scotland, May 31, 2013, nrscotland.gov.uk/research/learning/hall-of-fame/hall-of-fame-a-z/hunter-john.

- Helle Mathiase, “Mastectomy without Anesthesia: The Cases of Abigail Adams Smith and Fanny Burney,” The American Journal of Medicine, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.01.004.

KINGSTON BRIDGES is a high school senior at the American School in London with a passion for medicine and history. He worked at Carling Dental as a summer intern and at the US embassy to the United Kingdom. He is excited to continue his studies into university in the US. The author wishes to thank Dr. James L. Franklin for mentoring him in the composition of this article.

Summer 2023 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply