Michael Ellman

Wilmette, Illinois, United States

|

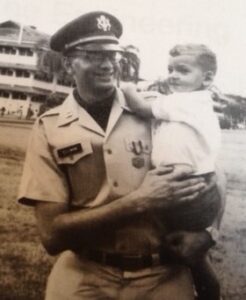

| Captain Michael and son at the medal ceremony, 1968. |

In 1965, I became the Chief Preventive Medicine Officer of the United States Southern Command. One of the eleven unified commands of the Department of Defense, the Southern Command was headquartered in the Panama Canal Zone and represented our interests in South America, Central America, excluding Mexico, and the Caribbean—but not Cuba.

The Army had paid for my senior year of medical school, and, in return, I would serve for three years instead of two, have priority with assignments, and be able to complete my medical training. I guess I had not read the fine print. Drafted immediately after my internship, I was enrolled in the Army’s preventive medicine school in San Antonio, Texas, and then sent to the Canal Zone, where I would oversee mosquitoes, heat related disorders, snakes, sanitation, and venereal diseases.

Colonel Bob was the Chief Medical Officer. He was a regular Army doctor, a quietly competent administrator practicing no medicine, a Purple Heart awardee from a battle wound in Korea. He was easy going comfortable with daily military life, and he took a kind hand in helping me with my responsibilities.

“Colonel Bob,” I said. “I received a phone call from General Franklin’s office telling me to see him tomorrow at 8 AM to discuss the venereal disease problem.”

The Canal Zone had the second highest venereal disease rate in the U.S. Military.

I was on my own. There was no good blood between the General and Colonel Bob. It was a longstanding problem but exacerbated by a recent event.

The General, whose headquarters were only a mile away, would helicopter to our clinic and offices whenever he needed us. He had arrived for a new pair of glasses, something we could not manufacture there. The General had sustained a facial wound and required a special lens for his right eye. The specifications were forwarded to an Army facility in Colorado, and the new pair was sent by military plane to our Howard Air Force Base.

We gathered around as instructed by Colonel Bob after the General’s helicopter arrived, and the Colonel presented him with his new glasses.

General Franklin handed his old pair to his Sergeant, carefully adjusting the new one around his ears, a brief smile sneaking out from his stiff military conceit, while stopping to appraise the gathering. Then he removed the glasses, stared at them for a moment before throwing them into the lobby wall, where the plastic and glass shattered in disarray. The right eye lens had been inserted in the left side.

“What the f—!” he said, pointing his finger at Colonel Bob and stomping out to his waiting helicopter.

* * *

“Captain,” the General said to me, “let’s talk about preventing venereal disease.” The General was resplendent in combat fatigues. His steel helmet and holstered .45 caliber pistol were layered on his desk such that I needed to look over the paraphernalia to see him.

“There’s a ruckus in downtown Panama City and ‘Be prepared’ is my motto,” he said pointing to his pistol. “When I took this assignment, I promised myself to help the boys and reduce their venereal disease burden. It’s not just the high rate,” he said, “it’s the worry that my boys will go home to their family with destroyed brains and faces and all the stuff down below.”

It was clear that the General was probably confusing syphilis with leprosy, but I was instructed by Colonel Bob to say “Yes, sir” to everything.

“Sir,” I said, “we have been thinking about this problem, and Colonel Bob and I thought offering free supplies of condoms to the troops might reduce the number of infections.”

“F—, no,” the general said, “Encouraging the boys to f— the natives was not what I had in mind. That is why, thanks to me, we have free movies during the weekends, baseball tournaments, ping pong tables, and the new bowling alley. Have you tried bowling? Eight lanes. Those should be keeping the boys busy on weekends.”

“Yes, sir,” I said.

I was charged with lecturing the troops about the consequences of going home without a nose, becoming sterile, and being brain dead. Everyone attended my presentations. Colonel Bob and the pathologists at Gorgas Memorial Hospital, our civilian and military hospital, supplied me with glass projection slides of genital cancers, scrotal infections, and leprosy disfigurements that I passed on to the troops as photographs depicting sexually acquired diseases. I could not view them without cringing, although my talks captured the boys’ attention like Betty Grable’s iconic showing of her “Million Dollar Legs” during her World War II visits to the troops.

Our VD rate doubled in the first month. I assured the General that was temporary. But our VD rate did not decline in the second or third month. My second visit to the General was not as congenial as the first one.

“Sir,” I said, “the good news is that now the troops are now receiving first-rate medical care by Army doctors with important and comprehensive follow-up for their disease. Many of them had been treated in downtown Panama City, where the pharmacies provided over-the-counter chloramphenicol, an oral antibiotic that we can’t use because of potential side effects, such as bone marrow depression.”

The troops bought into my exhortation that by seeing Army doctors, they would be tested for other venereal diseases such as syphilis, guaranteed that their privates and brains wouldn’t fall out, and there would be no need to tell their wives or girlfriends that they were unable to have children.

This new influx of patients had boosted our VD rate.

“Captain,” the General said, “if you ever lecture to the boys again, you will be reassigned. You are an embarrassment. Go back and tell Colonel Bob that the two of you have failed me. Dismissed!”

“Yes, sir,” I said, and I saluted and made an about face. I did not see the General again until my departure from the Canal Zone and return to civilian life.

* * *

Remembrance is a private thing, and some memories refuse to stay in their box. A catalog of fungible Army topics other than VD prevention would sometimes interrupt my sleep. Snakes for instance—our public service announcements advised those bitten to bring the snake with them. Seeing a fer-de-lance, or a bushmaster, or a coral snake in the emergency room was bad dream worthy.

There also was the “ruckus” in Panama City that morphed General Franklin into George Patton. Anti-American riots occurred monthly in Panama and all of them had the same modus operandi: no one was injured, advance notice was provided, space for photographers was cordoned off, and the angry but cautious Universidad students met at the intersection of Calle 50 and Avenida Balboa, a popular location, where a preselected car would be burned. Photographs of these events would appear in our hometown newspapers and were sent to us from family and friends with heart-felt pleas to be careful. The Panama Canal Zone, except for the snakes and the VD, was the safest place to be in the Western Hemisphere.

The April medal ceremony was near the end of my Army career. The dry season was ending and everything was so brown it ached. All the recipients of medals except me were Vietnam returnees receiving Purple Hearts, Bronze Stars, and awards of that ilk. They were heroes, but the General stopped in front of me, surrounded by his coterie of sycophants, and pinned the Army Commendation Medal on my chest. That medal was awarded soldiers for such valor as coming to work every day.

“Captain,” the General said, “I hope you were more successful preventing malaria than you were stamping out VD.”

“Sir,” I wanted to say, “wait until you see my report about the drug resistant falciparum malaria strains from Asia that are now showing up in the Canal Zone,” but he did not give me the opportunity.

MICHAEL ELLMAN, MD, is a retired professor of medicine at the University of Chicago and a writer. His collection of short stories, Let Me Tell You About Angela, was well received and was an Eric Hoffer Award Finalist. His novel, Code-One Dancing, is also worth reading.

Summer 2023 | Sections | War & Veterans

Leave a Reply