Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

“[If] men could menstruate…menstruation would become an enviable, boast-worthy, masculine event.”1

– Gloria Steinem, journalist and political activist

Ancient history has shown us that men sometimes looked upon women’s menstrual periods with perplexity, wonder, and fear.2 While it has been suggested that some men have “vagina envy” and “womb envy,” and feel left out of the processes of pregnancy and childbearing,3 many cultures and religions have historically stigmatized menstruation and menstruating women as being unclean.4 Menstruating women were once thought to have a “dangerous supernatural power,” and men therefore created taboos to avoid women during their menses.5 A 1974 survey6 of forty-four cultures worldwide showed that in thirty of thirty-three for which there was information, menstrual fluid was believed to be “contaminating or dangerous.”

Some writers have maintained that for men, the beginning of menstruation (called menarche), as well as subsequent menstrual periods, are disgusting and ugly. Portrayals of menarche in horror films suggest that the onset of menstruation may lead to one of two outcomes for women: accepting the biology of femaleness and preparing for sexuality, reproduction, and motherhood (the “normal” path); or, if things go terribly wrong, becoming involved in the supernatural.7 In such portrayals the adolescent girl may become telekinetic, a monster, or a victim of diabolic possession. These portrayals would suggest major societal problems, since “normality is threatened by the monster,” according to Robin Wood, a pioneering film critic.8

Carrie9,10

|

| Carrie (1976) theatrical poster. Via Wikimedia. Fair use. |

The film Carrie (1976) tells the story of Carrie White, a shy girl lacking self-confidence who is the high school scapegoat, universally disliked by all the other students. The film starts in the girls’ locker room. We see well-proportioned adolescent girls (“nymphs”11) drying themselves, joking with each other. Carrie is still under the shower and she sees that she is bleeding. She had never been told about menstruation. Her mother is a religious fanatic and has never discussed sex or reproduction with her daughter. Carrie is terrified, has no idea of what is happening, and runs out of the shower, asking the other girls for help. They turn on her, jeering, “Plug it up!” As she sits sobbing in a corner, they pelt her with tampons and sanitary napkins. Suddenly, an overhead lightbulb breaks. The physical education teacher hears the uproar, enters the locker room, and calms Carrie down. In the principal’s office, the principal keeps calling Carrie by the wrong name. An ashtray flies off the desk and onto the floor. Carrie goes home and looks for comfort from her mother, who tells her that her period started as a result of the sin of masturbation. She smacks her with a Bible, makes her repeat statements of guilt, and locks her in the “prayer closet.”

The teacher punishes the girls for their cruelty to Carrie and one girl vows revenge. Another girl feels sorry for Carrie and convinces her handsome athlete boyfriend to ask Carrie to the prom. Carrie starts wondering about the broken lightbulb and the flying ashtray, reads up on telekinesis, and understands that she has had that power since her menarche. This telekinesis may represent a “displaced eruption of the sexual repression enforced by her mother.”13 She eventually agrees to go to the prom. Her mother calls her a witch in “Satan’s power.” Carrie sews a pretty dress, and with the help of her teacher learns about lipstick and mascara. This would be an attempt to take the path of “culturally sanctioned femininity.”

Carrie is delighted to be at the prom with her handsome and attentive date. “It’s like being on Mars,” she says. A rigged election makes her date and her “King and Queen of the Prom.” They are invited up to a platform, where the radiant Carrie receives a large bouquet of flowers. At this point, a bucket of pig’s blood set up in the rafters is dropped upon Carrie, drenching her in blood. In her rage and sorrow, she telekinetically locks the doors, has the fire hoses flood the room, causes some of her tormentors to be electrocuted, and sets the building on fire. She leaves the school, comes home, and asks, “Mamma, please hold me.” Her mother says, “I should have given you to God when you were born.” She raves about her own sexual guilt because she enjoyed the intercourse with her then-husband by whom Carrie was conceived.14 She stabs Carrie, and Carrie telekinetically sends a number of knives into her mother. Carrie then sets the house on fire and it collapses. Both women die. Carrie has been described as the film that is the best “touchstone for the association of evil with menstruating women.”15

Ginger Snaps16

|

| Ginger Snaps (2000) theatrical poster. Via Wikimedia. Fair use. |

The film Ginger Snaps (2000) also takes place in a homogenous suburb, this time in Ontario, Canada. Ginger Fitzgerald, age sixteen, and her sister Brigitte, fifteen, are also outsiders, but by choice. They dislike the superficial, sex-obsessed kids they go to school with, they dress in baggy, dull dresses, and are obsessed with death. There have been some unexplained killings and maulings of dogs in their town. On night, during a full moon, the sisters are crossing a wood and Ginger begins to menstruate for the first time, which would be considered medically late for menarche. Ginger is attacked and by bitten by some animal. Brigitte wonders if it was attracted by the smell of her sister’s menstrual blood. The animal is run over and killed by a car. Ginger starts growing some hair on her chest. The sisters visit the chirpy, insincere school nurse who explains menses and the bodily changes that accompany them and assures Ginger that everything is fine.

Their mother sees Ginger’s bloody underwear in the laundry and bakes a cake with red sauce to congratulate her daughter. The girls’ father, a nonentity, cannot tolerate the idea of even discussing menses during dinner.17 Younger sister Brigitte suspects that Ginger was bitten by a werewolf and is slowly turning into one. Ginger denies the possibility, but her canine teeth are lengthening and she kills and partly eats a neighbor’s dog. This movie has been called the first one in which the werewolf “has a feminine perspective.”18 (The word “werewolf” derives from the Old English wer, meaning man.) As Ginger’s condition progresses, she becomes more interested in boys and specifically in sex. At her first sexual intercourse she practically attacks the boy she is with. She also bites him, which transfers the werewolf infection to him. She needs to shave the fur off her legs. Her nails are becoming claws, and a tail appears. Her gradual transformation is unlike that in more typical werewolf stories, where the infected victim “can control the animal side as long as the moon is not full.”19 During the course of the film, Ginger kills the school guidance counselor and the school janitor. She tells Brigitte that it feels good to kill people, “like touching yourself.” When Brigitte brings up the possibility of a cure, Ginger responds, “You think I want to go back to being a nobody?” Finally, werewolf-Ginger attacks Brigitte and is killed by her. Like Carrie, Ginger did not menstruate “normally,” nor did she successfully negotiate puberty. The film suggests that “puberty and monstrosity are interchangeable”20 and that “menstruation [is] a precursor—or even a prerequisite—for…committing acts of violence.”21

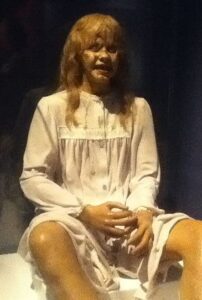

The Exorcist22,23

|

| Possessed Regan dummy. Crop of photo (“Excorcist puppet”) by Pollack man34 on Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 3.0. Fair use. |

Regan MacNeil is a twelve-year-old girl “on the brink of puberty”24 who lives with her divorced mother in the upper-class neighborhood of Georgetown in Washington, DC. She seems to be a normal girl but begins acting strangely. She progresses from saying odd things, to shaking her whole bed without apparent effort, to speaking in different voices that claim to be the Devil. She says filthy things, uses telekinesis, and performs physically impossible acts, such as rotating her head 360 degrees.

She masturbates with a crucifix, although no one can explain how it got into her room. She has a vaginal flow of blood. Some critics have questioned whether this is her menarche beginning, plus trauma from the masturbation, or trauma alone.25 While under this demonic possession, she spews green vomit and is later responsible for three deaths. In an attempt to find a reason for a suspected temporal lobe epilepsy, a neurologic evaluation is of no help, and neither is invasive brain imaging (a cerebral arteriogram). The neurologists suggest a psychiatric evaluation, which is also unhelpful. One of the psychiatrists suggests that the only approach left is an exorcism, which is performed by two Catholic priests from Georgetown University. The older one, already ill, dies during the long and difficult exorcism. The younger Jesuit tells the demon, “Take me.” The demon seems to leave Regan and enter the priest (a bigger prize), who then jumps out the window.

Some have seen a flavor of Victorian psychiatry, which linked “’female insanity’” to the “’biological crises of the female life-cycle’” (i.e. puberty, pregnancy, childbirth, and menopause), in The Exorcist.26 One criticism of the film is that it is a male picture of female puberty, in which “the emergence of woman’s sexuality is equated with demonic possession,” and men unite to “torture Regan in their efforts to return her to her pre-sexual innocence” and bring the “old Regan” back.27 Or as physician and anthropologist Melvin Konner states it, “Menstrual blood is the mortar with which the house of gender difference and gender bias is built.”28

References

- Gloria Steinem. “If men could menstruate,” in Chris Bobel et al, eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies (internet), Singapore: Palgrave MacMillan, 2020.

- Kate Lister. A Curious History of Sex. London: Unbound, 2021.

- “Womb envy.” Wikipedia.

- Lister, Curious History.

- Kayla Davidge. “Why and when did menstruation become taboo?” Your Period Called, January 13, 2021.

- Rita Montgomery. “A cross-cultural study of menstruation, menstrual taboos, and related social variables.” Ethos, 2(2), 1974.

- Kate Maher. “The vagina as a bleeding wound: Monstrous puberty in Carrie, The Exorcist, and Ginger Snaps.” Academia, 2014. https://www.academia.edu/9476703/Menstruation_in_horror_films.

- Michael Conte. “Red, Carrie White, and blue: Viewing Carrie as a symptom of the cultural anxieties experienced by Americans in the 1970s.” Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies, 5(1),2014.

- Steven King. Carrie. London: Holder & Stoughton Ltd, 1974.

- Lawrence Cohen, screenplay, Brian DePalma, dir. Carrie. Red Bank Films, 1976.

- Shelley Lindsey. “Horror, femininity, and Carrie’s monstrous puberty.” Journal of Film and Video, 43(4), 1991.

- Aviva Briefel. “Monster pains – masochism, menstruation, and identification in the horror film.” Film Quarterly, 58(3), 2005.

- Lindsey, “Horror.”

- Leigh Ehlers. “‘Carrie’ book and film.” Literature/Film Quarterly, 9(1), 1981.

- Erika Thomas. “Crimson horror: The discourse and visibility of menstruation in mainstream horror films and its influence on cultural myths and taboos.” Relevant Rhetoric, 18, 2017.

- Karen Walton, screenplay, John Fawcett, dir. Ginger Snaps. Motion International, 2000.

- April Miller. “‘The hair that wasn’t there before’: Demystifying monstrosity and menstruation in ‘Ginger Snaps’ and ‘Ginger Snaps unleashed.’” Western Folklore 6(3/4), 2005.

- Pascale Fakhry. “‘Something’s wrong, like more than you being just female’: Corps féminin et personnages-type du film d’horreur gore dans Ginger Snaps.” Corps, 1(9), 2011.

- Bianca Nielsen. “‘Something’s wrong, like more than you being female’: Transgressive sexuality and discourses of reproduction in Ginger Snaps.” Thirdspace, 3(2), 2009.

- Rebecca Sterling. “Monstrous journeys: The horror of the failed female hero’s journey in Carrie and Ginger Snaps.” (Thesis) California State University at San Marcos, 2017.

- Briefel, “Monster pains.”

- William Blatty. The Exorcist. New York: Harper and Row, 1971.

- William Blatty, screenplay, William Friedkin, dir. The Exorcist. Warner Brothers, 1973.

- “What the ever-popular ‘Exorcist’ says about female sexuality,” Magazine, November 11, 2010.

- Maher, “The vagina.”

- Eszter Balogh. “Demonic obsession and madness in The Exorcist (1973),” in Fanni Feldman, ed. Anglo-American Voices 1. (En)Gendered Lives, Debrecen (Hungary): Hatvani István Extramural College, University of Debrecen, 2016.

- Adrian Schober. “The lost and possessed child in Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw, William Friedkin & William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, and Victor Kelleher’s Del-Del.” Papers: Explorations into Children’s Literature, 9(2), 1999.

- Melvin Konner. The Jewish Body. New York: Schocken Books, 2009.

HOWARD FISCHER, M.D., was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Summer 2023 | Sections | Books & Reviews

Leave a Reply