JMS Pearce

Hull, England

|

| Davidson’s The Principles & Practice of Medicine, 1956 edition. |

A textbook of medicine is a single work covering all the major specialist topics, aimed principally at the undergraduate medical student. What constitutes a good textbook of medicine is plainly a subjective judgment; it would be invidious to select one of many excellent books. If we judge quality and value by the number of editions published—an index of popularity and usage—then Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine in its 24th edition (1st edition 1952) must be considered one of the finest, and was certainly my medical student bible (3rd edition 1956). Postgraduates too, need a basic reference work of this type although they rely more on individual monographs, scientific papers, and reviews devoted to specialist subjects.

Multiauthor books aim to provide specialized, authoritative accounts of the contained subjects. Early editions of Davidson had contributions from fourteen authors and, unlike many recent multiauthor works, managed to retain a consistency of high quality, readability, and succinct style. They were concise with systematic accounts of diseases, their etiology, pathology, clinical features, prognosis, and treatment. These are now confined to the third section of the book but are preceded by practical, lucid, and comprehensive accounts of the “Fundamentals of Medicine” and “Emergency and Critical Care Medicine.”

Its popularity continues in its 24th edition (2022). More than two million medical students, doctors, and other health professionals have owned a copy of Davidson since it was first published. It is currently large (1,378 pages), edited by Ian D. Penman, Stuart H. Ralston, Mark W.J. Strachan, and Richard Hobson, and available as a paperback. There is a shorter version: Davidson’s Essentials of Medicine, 3rd Edition (2020), by J. Alistair Innes.

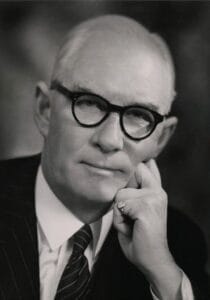

Leybourne Stanley Patrick Davidson

|

| Sir Stanley Davidson. © National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG x86946. |

Stanley Davidson (1894–1981) was born in Ceylon, son of Sir Leybourne Davidson, a prosperous tea and rubber merchant. He was educated at Cheltenham College and Trinity College, Cambridge, but read medicine in Edinburgh.

His Cambridge studies were interrupted: “the day war broke out I jumped on a motorbike with a Cambridge student and joined the Gordon Highlanders and by 1916 I hadn’t one living person from that class at Cambridge alive, not one.”1 He was twice wounded, the second time so seriously that he was in hospital for almost two years. Still convalescing, back in Edinburgh in 1917 he continued his medical studies, graduating with first class honors in 1919. He later remarked: “I never did any work before the war, I did nothing but play games all the time. I played for Trinity tennis, hockey and rugby, all of them. … but the Kaiser’s war completely altered my life.” Advised that he was physically unfit for a clinical career, he worked in bacteriology and obtained his MD with gold medal; his thesis was on immunization and antibody reactions.

He then concentrated on hematology and rheumatic diseases as an able researcher, producing an important monograph on pernicious anemia, followed by papers on vital staining of erythrocytes and the classification and treatment of anemias. With Sir Derrick Dunlop and John W. McNee he wrote The Textbook of Medical Treatment. In 1930 he was appointed professor of medicine in Aberdeen, but in 1938 he returned to Edinburgh to the chair of medicine. With Sir Derrick Dunlop and Rae Gilchrist, he radically reorganized Edinburgh medicine, attracted physicians from more southern climes, and furthered the development of major medical specialties. A Polish School of Medicine was founded in Edinburgh in 1941 in which he acted as head of the department of medicine until it closed in 1949. In 1959, with A.P. Meiklejohn and R. Passmore, he produced a large monograph titled Human Nutrition and Dietetics.

|

| Davidson’s grave, Currie Churchyard, Edinburgh. Crop of photo by Stephencdickson on Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 4.0. |

He was hugely successful. For his services to medicine he was knighted in 1955, and from 1947 to 1952 was physician to King George VI in Scotland, then to Queen Elizabeth II. He was President of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh from 1953 to 1957, Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1932, and received many honorary doctorate degrees.2

Described as a free spirit unshackled by convention, an interview with Angus Stuart in 1973 revealed insights of his career and an irrepressible, colorful personality.1 He was a fine athlete in his youth, a keen fisherman, golfer, and shot.

He married Isabel Margaret Anderson in July 1927 in Edinburgh. She died in 1979. They had no children. He made substantial donations to the medical schools of the chief Scottish cities and to the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.3 Sir Stanley died on 27 September 1981 and was buried in the ancient stone vault of his ancestors in Currie churchyard, near his family home.

References

- Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Stanley Davidson Interview. YouTube video, 1:15:26, Mar 26, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xsHzQwYpxdA. Archive Reference: OBJ/ORA/1/10.

- Obituary. Sir Stanley Davidson. Brit Med J 1981; 283, 993, 1131.

- Robson J, Matthew H. Davidson, Sir (Leybourne) Stanley Patrick (1894–1981), physician and haematologist. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/31008.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.