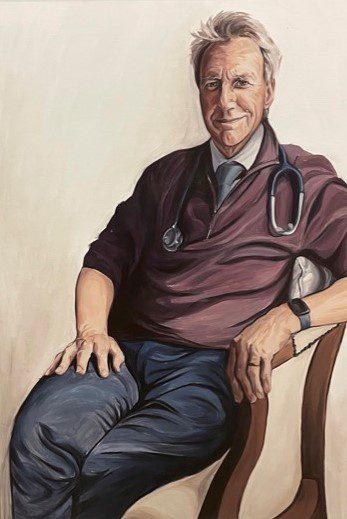

Terrence Stephenson

London, England

A whole cohort of cancer survivors owe both their lives and the conception of their children to a group of pediatric oncologists and colleagues from many disciplines spanning medicine, science, and the humanities. Their work brought to fruition and revolutionized the long-term care of childhood cancer survivors around the world and is an example of what can be achieved with determination, passion, and collaboration. One of the leaders of this work has been Professor Hamish Wallace.

By the 1980s, a whole range of “late effects” had been described in survivors of childhood cancer, from an increased risk of second cancers following external beam irradiation to heart damage from anthracycline exposure. But many of the other emerging late effects were endocrinological: pan-hypopituitarism, growth hormone insufficiency, thyroid dysfunction, and hypogonadism. As a result, many adult survivors of childhood cancers were infertile.

I first met Hamish Wallace as a young doctor—thoughtful, reflective, a keen teacher. Hamish was interested in both pediatric endocrinology and oncology, and ultimately combined the two by developing a special interest in the late effects of treatment in survivors of childhood cancer. After clinical training in pediatric oncology at , London, and the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, in 1988 Dr. Wallace took up a research post at the Christie Hospital in Manchester. There he studied the effects of cis-platinum on gonadal function; the effects of treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia on male and female gonadal function; and the effect of therapeutic radiation on ovarian function,1 which he continued to study with colleagues in Edinburgh. In his MD research thesis, he postulated that in the absence of chemotherapy, in healthy women, the number of ovarian primordial oocytes declines following a model of exponential decay.2 Working with Thomas Kelsey at St. Andrews University, Scotland; Chia-Ho Hua from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, Tennessee; and Amber Wyatt and Danny Indelicato from the University of Florida at Jacksonville, he produced a predictive model of the effect of therapeutic radiation on the human ovary.3 This work helps inform young female cancer patients about their chances for natural fertility once treatment is completed and, for some patients, options for fertility preservation.

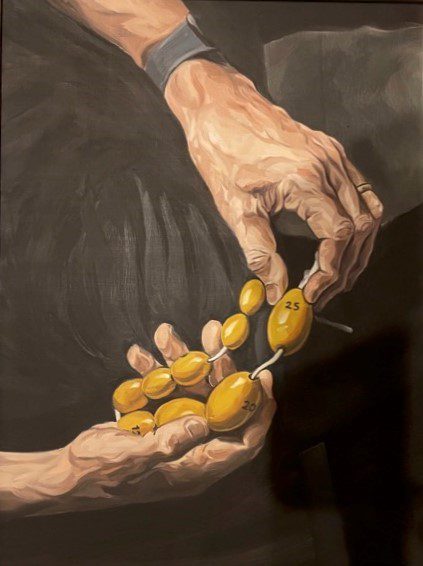

Wallace and Kelsey were also among the first to identify the key issue in investigating treatments to mitigate this—the need for the natural baseline trajectory to then quantify the late effects of cancer therapy. Their understanding of the effects of radiation on the human ovary led to a new model, which has been externally validated and describes the number of immature primordial follicles (oocytes) in the human ovary from birth to menopause.4 An important outcome from this collaborative research into the effect of cytotoxic treatment on ovarian function in young women with cancer has been the development of a better understanding of the normal physiological decline of primordial oocytes in healthy women.

Dr. Wallace moved from Manchester to take up a post as a pediatric oncologist at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Edinburgh, in 1992. Despite no protected time for research, he was driven by a passion to continue his previous field of research and help restore the fertility of young women who had survived cancer in childhood. He formed a close and highly successful research collaboration with academic colleagues at the University of Edinburgh, initially working with Hilary Critchley on uterine function and Richard Anderson on ovarian function. With Dror Meirow in Jerusalem, he published pioneering work on fertility preservation.5 Wallace also reported that ovarian failure was especially likely with alkylating agents and platinum-derived chemotherapy. If these agents are essential, the option to freeze ovarian tissue or oocytes should be discussed with the young person and family before treatment begins.6 With David Baird, Richard Anderson, and others, it was shown that it was possible to freeze and transplant ovarian tissue successfully in a sheep model. Building on this experimental work, Jacques Donnez and Marie-Madeleine Dolmans in Belgium reported the first live birth following ovarian transplant in 2004. Today, ovarian tissue freezing before cancer treatment begins is offered to many young girls and women whose future fertility is at risk. Transplantation for those seeking a pregnancy is available in many developed countries, with a 50% successful live birth rate.7

However, for these clinicians and researchers, it was not enough just to restore ovarian function in survivors of childhood cancer. They were also able to demonstrate improved uterine function in addition to the previous work on ovarian fertility. Women with premature ovarian insufficiency are not only infertile but also at risk of osteoporosis and cardiovascular effects. Wallace, with Critchley, Chris Kelnar, and others, investigated the role of physiological sex steroid replacement therapy in improving the health of these young women with premature ovarian insufficiency.8

These innovations and their translation into mainstream medicine generated a number of ethical issues. Not least because these challenging discussions with pre-pubertal girls and boys or peri- or post-pubertal young women and men and their families, and any consequent procedures, have to be conducted without leading to delays in lifesaving cancer treatment. Dr. Wallace was an important voice in achieving consensus around a two-step consent process—for initial tissue harvest of cells capable of reproduction and then later for fertility restoration—the “Homerton consensus” on fertility preservation and pre-treatment germ cell harvest.9 These far-sighted concepts are more topical than ever, having been revisited recently in relation to transgender issues in the Bell v. Tavistock case at England’s Court of Appeal.10

By 2010, 1 in 250 members of the adult population in developed countries were survivors of childhood cancers. Of these, 44% had an endocrine disorder (most commonly growth hormone insufficiency, hypopituitarism, hypogonadism, or a combination of all three). Many of the concepts described above are captured in a leading textbook co-written by Professor Wallace.11 As the wonderful illustrations depict, a whole cohort of cancer survivors owe both their lives and their fertility to the research and clinical procedures developed by the multidisciplinary approach of the healing arts and the humanities, bringing together medical, scientific, ethical, and legal collaborators.

References

- Wallace WH, Shalet SM, Crowne EC, Morris-Jones PH, Gattamaneni HR. “Ovarian failure following abdominal irradiation in childhood: natural history and prognosis.” Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 1989;1(2):75-9.

- Wallace WH, Shalet SM, Hendry JH, Morris-Jones PH, Gattamaneni HR. “Ovarian failure following abdominal irradiation in childhood: the radiosensitivity of the human oocyte.” Br J Radiol 1989;62(743):995-8.

- Kelsey TW, Hua CH, Wyatt A, Indelicato D, Wallace WH. “A predictive model of the effect of therapeutic radiation on the human ovary.” PLoS One 2022;17(11):e0277052.

- Wallace WH, Kelsey TW. “Human ovarian reserve from conception to the menopause.” PLoS One 2010;5(1):e8772.

- Meirow D, Wallace WH. “Preservation of fertility in patients with cancer.” N Engl J Med 2009;360(25):2682.

- Wallace WH, Smith AG, Kelsey TW, Edgar AE, Anderson RA. “Fertility preservation for girls and young women with cancer: population-based validation of criteria for ovarian tissue cryopreservation.” Lancet Oncol 2014;15(10):1129-36.

- Donnez J, Dolmans MM. “Fertility Preservation in Women.” N Engl J Med 2017;377(17):1657-65.

- Langrish JP, Mills NL, Bath LE, Warner P, Webb DJ, Kelnar CJ, Critchley HO, Newby DE, Wallace WH. “Cardiovascular effects of physiological and standard sex steroid replacement regimens in premature ovarian failure.” Hypertension 2009;53(5):805-11.

- Grundy R, Larcher V, Gosden RG, Hewitt M, Leiper A, Spoudeas HA, Walker D, Wallace WH. “Fertility preservation for children treated for cancer (2): ethics of consent for gamete storage and experimentation.” Arch Dis Child 2001;84(4):360-2.

- EWCA Civ 1363 Appeal No. C1/2020/2142 Case No CO/60/2020. Courts and Tribunals Judiciary 2021. https://www.judiciary.uk 17 Sept 2021.

- Late effects of childhood cancer. Hamish Wallace and Daniel Green, eds. Arnold, London (2004; eBook Dec 2012).

SIR TERRENCE STEPHENSON is Chair of England’s Health Research Authority. Previously, he was Chair of the UK General Medical Council and the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges; President Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. He was knighted in 2018 and elected an honorary Fellow of eleven national Colleges or Academies in the UK, Ireland, Hong Kong and Australia.

Leave a Reply