Amairani Gómez Rodríguez

Puebla, Mexico

|

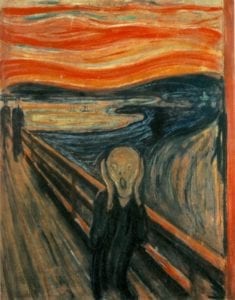

| The Scream by Edvard Munch, 1893. National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo, Norway. |

I had my first panic attack at seventeen. Biochemistry was a total headache; no matter how hard I studied, it was never enough to pass. As a school overachiever, I had never experienced failure. I felt an existential pressure.

My supportive family never demanded high marks or my being the top student. I felt, however, that it was not enough to be “a medical student.” I had to be the best. But the first hurdle I faced distressed me. My heart raced and I could not stop crying, and the ten minutes I took to calm down felt like the end of the world.

We medical students face hard situations—not just because of daily medical practice, but because we meet sick people who deal with serious socio-economic problems. We also work long day-and-night shifts.

In Mexico and Latin America, physicians and students endure a pathological learning model. No matter how brilliant you are or how hard you try, you will be told you are not good enough.

According to a 2018 survey conducted by Stéphanie Derive et al, the most frequent abuse experienced among 143 medical residents in the State of Mexico was psychological, followed by academic, and to a lesser extent, physical. 21% of residents reported having been pressured to consume alcohol. 60% were victims of robberies, and 35% reported an obligation to pay hospital staff for benefits during residency.1 Abuse also occurs during our first internship rotations. These factors cause mental stress.

We physicians understand the physiopathology of mental illnesses; we are told to be kind to such patients. This kindness does not, however, seem to be shown to our colleagues. Stigma and discrimination of Latin American health workers with mental health issues are not uncommon.

I started being treated for anxiety just before my internship. I had trouble equaling my classmates’ rhythm. In obstetrics, I started having suicidal thoughts.

Sadly, my case is not isolated. A 2016 JAMA meta-analysis reported a crude prevalence of suicidal ideation in 11.1% of medical students.2 Thankfully, when I asked for help, I was listened to by the hospital authorities. Not everyone had this empathetic reception, and news of other students’ or residents’ suicides was not uncommon.2

Resuming my clinical rotations after a couple of months of intensive treatment was not easy. I experienced the stigma, not just from superiors, but from colleagues. I was told I was weak and that I was just faking my symptoms or using my “illness” to shirk my job. That was the worst part of it and almost made me crumble. Anxiety and depression not only ruined my personal life, but my work. I could not stop thinking about how empathetic my partners were with patients with mental health problems, but how they were not with me or with other students like me.

I remember when most of my friends had serious alcohol problems supposedly caused by exam stress or frustration with insufficient free time. Now I wonder if they were also struggling with mental health issues and chose not to talk about them for fear of being judged by others or by the people we looked up to.

It is sad to think that our basic sense of humanity might get lost at some point in our education. The learning model in most Latin-American medical schools proves unhealthy for the very people training to care for the health of others.

Perhaps that system once worked, but right now, it does not. I saw it in the eyes of friends during our internship. I saw them desperately wanting to be back home just to cry out the stresses of the day. I saw them leaving home on day one with bright eyes—and coming home disappointed.

I firmly believe that this can change. Perhaps the first step is to remind ourselves that we as physicians are also human, have feelings, are allowed to rest, and can be mentally ill. We deserve to receive the same kind treatment we give our patients. We all deserve empathy and humanity.

References

- Derive, Stéphanie, et al. “Perception of mistreatment during medical residency in Mexico: evaluation and bioethical analysis.” Investigación en educación médica 7, no. 6 (2018).

- Rotenstein, Lisa, et al. “Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” JAMA 316, no. 21 (2016): 2214-36.

AMAIRANI GÓMEZ is a twenty-four-year-old medical student in her last year. She is currently working at social service practices investigating rheumatoid arthritis. She wants to become a pediatric ophthalmologist to help prevent childhood blindness in Mexico.

Spring 2023 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply