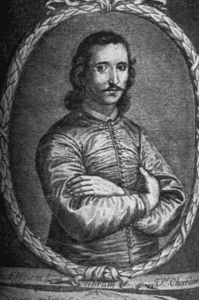

Walter Charleton was primarily a polymath but also a distinguished medical man. He read widely; wrote on religion, physics, physiology, psychology, geology, zoology, and botany; and is the listed author of thirty printed books and four manuscripts.1

One of his biographers mentions, without further comment, that the future physician made a sudden entry into this world by surprising his mother in the afternoon of February 2, 1619.1 Educated by his father in his native market town of Shepton Mallet in Somerset, he entered Oxford University in 1635 at age sixteen and received his medical degree in 1641. Two years later, in January 1643, he was appointed physician-in-ordinary to King Charles I.1

As William Harvey was in attendance to the king from 1642 to 1646, there was not much for Charleton to do. He met the famous John Locke, Robert Boyle, Thomas Willis, and many others. He performed anatomical research, collaborating with Willis to investigate the structure of the nerves, brain, and spleen, but was also busy practicing medicine. During most of the civil war between the king and Parliament, he busied himself making dissections and writing dissertations. During the Oxford siege he attended William Harvey.

In 1649 King Charles lost his head and Charleton lost his patron. After the royalist surrender of Oxford in 1647, he may have fled to France. In 1650, he established a medical practice in Covent Garden, but later also spent some time in the Netherlands and Paris. He was appointed physician-in-ordinary to Charles II, a purely honorary office since he did not accompany him in exile. As a royalist, he did not collaborate with Cromwell’s administration. He gained a reputation for his medical expertise and became popular with the English elite.

Charleton had wide interests, ranging from children’s teeth to how to make the best wine. He investigated the origins of Stonehenge and argued that its origins predated Roman times and was a meeting place for tribal chieftains of the Danes. He produced a witty play that was performed on the London stage. He composed a physiology textbook and wrote on medical topics such as the formation of urinary stones. He became part of the literary circle that included Thomas Hobbs and Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle. He wrote a dialogue on the immortality of the soul which consisted of a dialogue on learning, civil war, and morality.

Though highly regarded, Charleton never developed a consistent philosophy of his own and was regarded to have been the “intellectual barometer of the age.”2 He agreed that the material world consisted of atoms but admitted that these atoms were created by God. He was attracted by Epicureanism and its emphasis on ataraxia, tranquility, avoiding extremes of passion and distress, and avoiding public duties. He wrote on the nature of passions and on the evils of atheism. At one time, he compared his life to a rudderless ship where control was barely possible. But the famous poet John Dryden lauded his work as follows:

Such is the healing virtue of Your Pen,

To perfect Cures on Books, as well as Men3

After the Restoration, Charleton regained his position as physician-in-ordinary. He became influential in the Royal College of Physicians, rising from censor to president, giving prestigious lectures and becoming the Harveian librarian. He was elected to the Royal Society. He experimented with Robert Hooke and attempted to graft the skin of one dog to another and transplant a spur to the head of a rooster. He was also commissioned to study the speed of a bullet shot out of a musket. In 1678 he is believed to have been offered a chair of practical medicine at Padua, but declined it. As he grew older, his reputation waned, and he died an unhappy man, “aged and grave,” apparently subject to depression. He typifies the learned physician of his time, clearly hamstrung by having no effective remedies for his patients, but often famous for his erudition.

Further reading

- Humphry Rolleston. Walter Charleton. Bulletin of the History of Medicine Mar 1940;8(3):403-16.

- Eric Lewis. Walter Charleton and Early Modern Eclectisism. Journal of the History of Ideas Oct 2001;6(4):651.

- S.A. Golden. Dryden’s praise of Dr Charleton. Hermathena Autumn 1966:103:59.