JMS Pearce

Hull, England

[Mead] physician who lived more in the broad sunshine of life than almost any man

– Dr. Samuel Johnson (Boswell’s Johnson IV. 222)

|

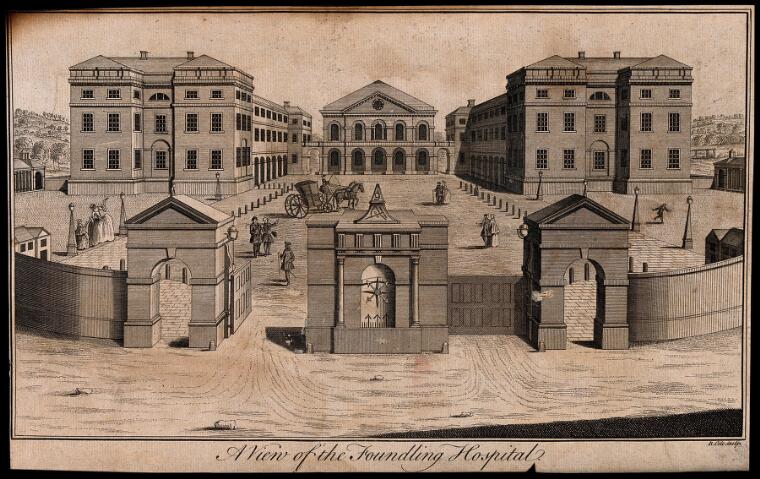

| Fig 1. The Foundling Hospital, Holborn, London. Engraving by B. Cole, 1754, after P. Fourdrinier, 1742. Wellcome Collection. |

The Foundling Hospital in Lamb’s Conduit Field in Bloomsbury (Fig 1) was established in 1739 to provide a safe home for children orphaned or abandoned, usually because of parental poverty.1 The museum’s gallery displays William Hogarth’s portrait of the Foundling Hospital’s founder, the benevolent sea captain Thomas Coram. After seventeen years of tireless campaigning, in 1739 Coram received the Royal Charter from King George II to establish the Foundling Hospital. Dr. Richard Mead, Arthur Onslow, and George Frederick Handel were founding Governors.

Mothers were asked to leave with their child a token such as a marked coin or scrap of fabric should they ever want to reclaim their child.2 Foundling children were baptized and sent to foster parents. At the age of sixteen, girls were apprenticed for domestic service; at fourteen, boys were apprenticed into various occupations, and many were trained for military service. William Hogarth and his wife Jane, who were childless, fostered many of the Foundling children.

The Foundling Hospital was a place of care, nurturing, and training for abandoned children.* Richard Mead created a pharmacy, advised on all aspects of care, and treated the children when they were ill. He also ordered a courtyard to be built for fresh air and exercise. Luther Holden of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, President of the Royal College of Surgeons, was elected Honorary Surgeon of the Foundling Hospital in 1864 and continued the tradition, started by Mead, of giving free advice to the hospital. Sir John Everett Millais bequeathed his portrait of Holden around 1880.

Over three centuries, more than 25,000 children were cared for by the Foundling Hospital. Catherine, Her Royal Highness The Princess of Wales, became Patron of the Foundling Museum in 2019.

Mead’s portrait

|

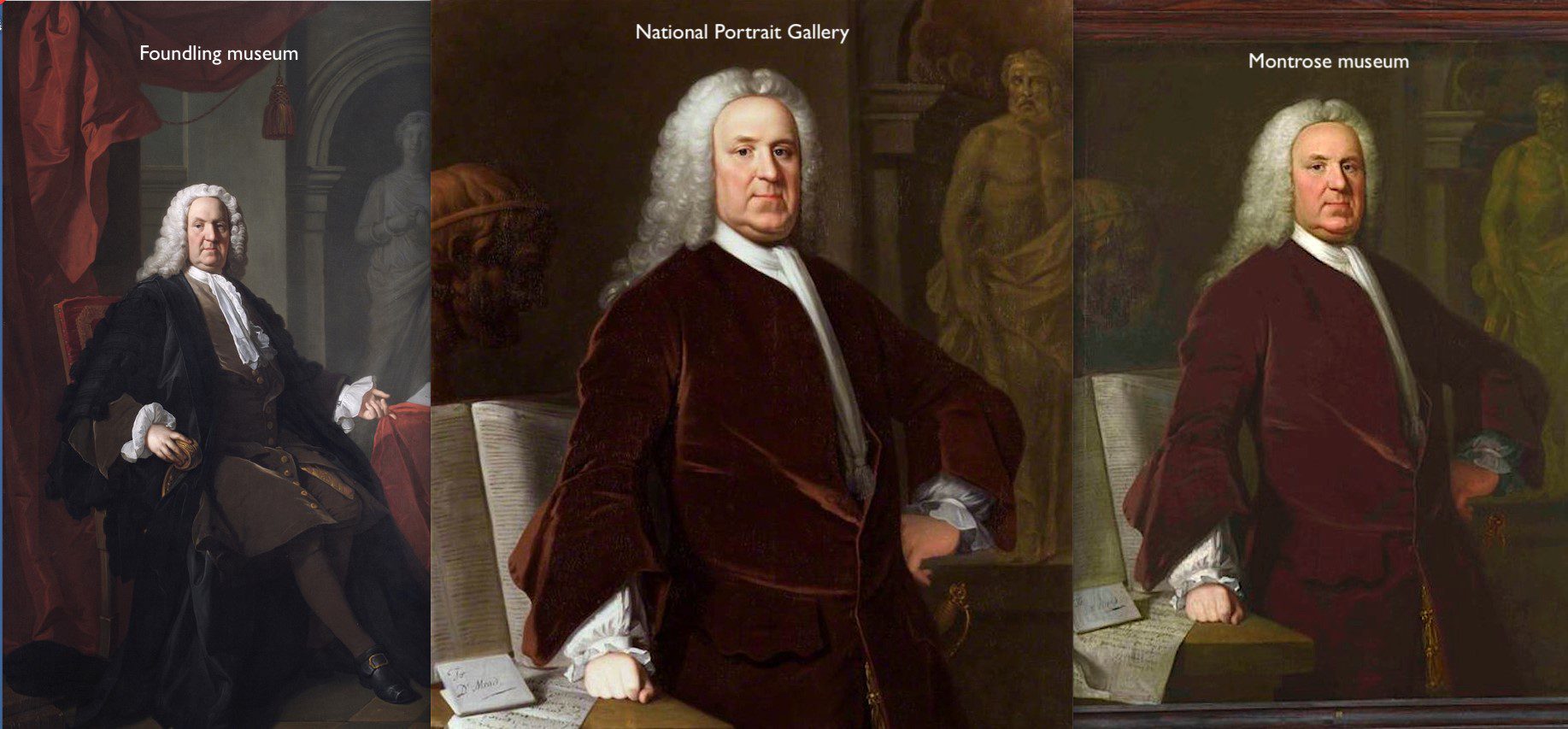

| Fig 2. Three portraits of Richard Mead: from the Foundling Museum (left), the NPG (center), and the Montrose Museum (right). |

Although familiar with Richard Mead and his portraits at the Royal College of Physicians, it was a surprise to see him reappear on Britain’s Lost Masterpieces, a BBC Four documentary series that uncovers overlooked art treasures.

A widely recognized portrait of Mead by the Scottish portrait artist Allan Ramsay is sited in the National Portrait Gallery (NPG 15) in London (Fig 2).

But from the storerooms of the Montrose Museum in Scotland, the BBC program uncovered an almost identical portrait with a large hole in it of Richard Mead by Ramsay. After minute scrutiny and search for provenance by art historians Bendor Grosvenor and Jacky Klein with restoration by Simon Gillespie, the Montrose painting was recognized as the original portrait by the authority Duncan Thomson.3 The NPG painting, dated 1740 and purchased in 1857, was considered “from his studio.”

In the Foundling Museum is another authentic portrait signed and presented by Allan Ramsay himself of Mead, dated 1747. Mead is erect, and the hands and left elbow are in different postures compared to the Montrose and NPG portraits. Mead had sponsored the youthful Ramsay’s “grand tour” to Italy in the 1730s and on his return used his powerful influence to help him become a fashionable portraitist, eventually appointed Principal Painter to King George III.

Richard Mead, MD, FRCP, FRS (1673–1754)

|

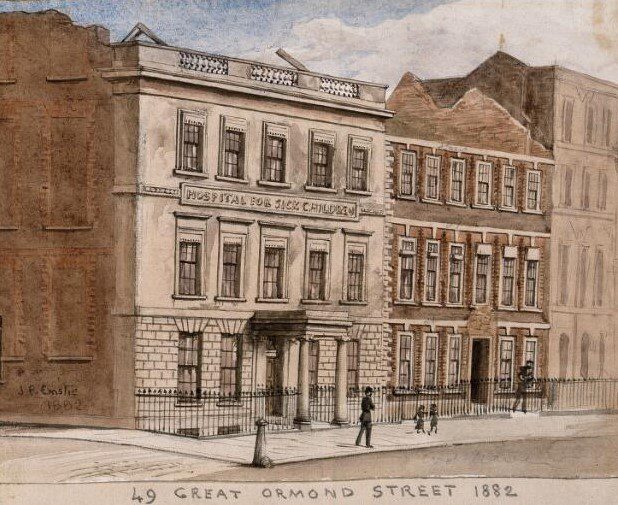

| Fig 3. 49 Great Ormond Street, London. Watercolor by JP Emslie, 1882. Wellcome Collection. |

Richard Mead was a polyhistorian, physician, philanthropist, and prolific collector of fine arts.4 His father, Rev. Matthew Mead, was a notable nonconformist. Richard, contemporary with Boerhaave, studied at Utrecht and Leyden and graduated Doctor of Philosophy and Physic at Padua in 1695.5 He left for the “grand tour” of Italy, returning to England in 1696 to practice medicine from his father’s Stepney home.

In 1699 Mead married Ruth Marsh, a merchant’s daughter, and joined the Church of England. They had eight children, of whom only three survived him. Two daughters married eminent physicians and his son Richard erected his memorial at Westminster Abbey.

In 1702 he published his Mechanical Account of Poisons. This work was greatly praised and established his reputation. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1703 and in the same year was appointed physician to St. Thomas’ Hospital, and taught anatomy at the Barber-Surgeon’s Hall. In 1707, the University of Oxford conferred upon him the MD degree. His work, A Short Discourse concerning Pestilential Contagion, and the Method to be used to prevent it (1720), was of historic importance in the understanding that contagion was caused by a living agent spread from one person to another,6 long before Pasteur and Lister. A mechanical account of poisons (1702) was one of Mead’s most influential publications. He was admitted a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians in 1716, Censor then Harveian Orator in 1723, but he declined the offer of its presidency.

An anniversary exhibition, The Generous Georgian in 2014, examined Mead’s work and life. It contained a Royal College of Physicians’ portrait of Mead with the famous gold-headed cane. John Radcliffe (1650–1714)—physician to King William III—for whom the cane was made,7 gave it to Mead along with his thriving practice and his Bloomsbury home (later the Hospital for Sick Children).

An expert on poisons, scurvy, smallpox, and public health, Mead was a keen advocate of inoculation against smallpox, which he had studied at Newgate Prison. Before Jennerian vaccination, 247 children were inoculated at the Hospital by 1756. Only one died of smallpox.

His memorial describes him as “mild and merciful in healing the sick and ever ready to assist the poor free of charge.” Bisset Hawkins, in The Lives of British Physicians, related:

In practice he had been absolutely without a rival; his average receipts had during several years amounted to between six and seven thousand pounds, an enormous sum …. So great was the anxiety to obtain his opinion, that he daily repaired to a coffeehouse in the City, and to another at the West End of the metropolis, to inspect written or to receive oral statements from the apothecaries, and to deliver his decision. His charity and his hospitality were unbounded; the epithet “princely” has often been applied to him on this head; but he has truly left an example which men of all ranks may be proud to imitate according to their means.

Mead was a collector of books, objets d’art, and coins. He obtained paintings by Rembrandt, Claude Lorrain, Brueghel, Rubens, and Titian. His paintings and antiquities (described as his great “Temple of Nature and Repository of Time”) were widely dispersed upon his death for the public good. Such was his reputation that several important books were dedicated to him, including William Cheselden’s Anatomy of the Humane Body (1713), William Baxter’s Glossarum antiquitatum Britannicarum (1719), and John Blackbourne’s The works of Francis Bacon (1730).

He attended King George I, Queen Anne, Sir Robert Walpole, Sir Isaac Newton, and Alexander Pope. In 1727 he was appointed physician to George II. Mead associated with many luminaries of the day, including the scientist Edmund Halley and artists William Hogarth and Allan Ramsay.

Mead is associated with nine portraits in the NPG, while a repository of his portraits is in the Royal College of Physicians, which also houses a marble bust of him by Roubiliac commissioned after Mead’s death by fellow physician and collector Dr. Anthony Askew.

William Munk described him as:

the most eminent medical practice of his time, consummate acquirements and literary labours important to the healing art, we shall find it difficult to select his equal among the annals of any period. Those excellent traits do not, however, complete his portrait; a noble frankness, suavity of manners, moderation in the estimate of his own merit, and a cordial acknowledgment of the deserts of his cotemporaries; liberality, not merely of purse, but also of sentiment, must be drawn in order to finish the likeness.8

His wife Ruth died in January 1720, and Mead moved to 49 Great Ormond Street (Fig 3). He married Anne Alston in 1724. His country estate was at Old Windsor in Berkshire, but he died at his Bloomsbury house in 1754. He was buried in the Temple church, but his memorial monument was placed by his son in the north aisle of Westminster Abbey. His Great Ormond Street home later formed the basis of Great Ormond Street Hospital for sick children.

Note

* In 1954 the hospital closed. Changing its name to the Thomas Coram Foundation for Children, the charity continued to accept children, finding them foster homes or arranging suitable adoption. Under the 1968 Children Act, the responsibility for care passed to local authorities.

References

- Nichols RH, Wray FA. The History of the Foundling Hospital. London: Oxford University Press, 1935.

- The creation of the Foundling Hospital. Coram Story. https://coramstory.org.uk/explore/content/article/the-creation-of-the-foundling-hospital/.

- McLaren R. 18th century art masterpiece discovered in Montrose after being neglected in storeroom. The Courier, October 7, 2016. https://thecourier.co.uk/fp/news/angus-mearns/296472/18th-century-art-masterpiece-discovered-in-montrose-after-being-neglected-in-store-room/.

- Carter HS. Richard Mead. Scot Med J 1958;3(7):320-4.

- Guerin, A. Mead, Richard (1673–1754), physician and collector of books and art. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004.

- Banerjee AK. Richard Mead. Hektoen International, Spring 2020.

- Pearce JMS. The Gold-Headed Cane revisited. Hektoen International, Summer 2019.

- William Munk. Richard Mead (1673–1754). Munk’s Roll: Lives of the Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians of London, Vol. II, 40.

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of medicine and science.

Spring 2023 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply