|

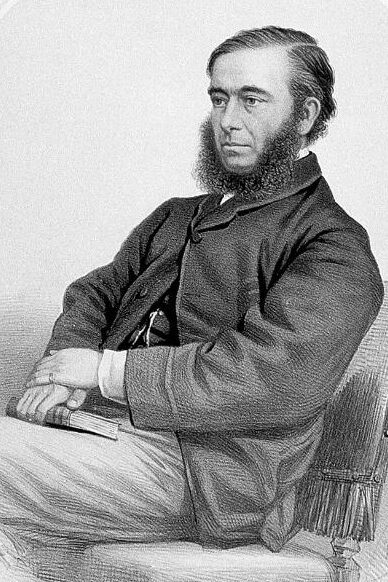

| William Budd. From lithograph published by A.B. Black, 1862. Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0. |

In the year 1811 when William Budd was born, medicine was still in its dark ages. Physicians dressed in black and wore top hats, surgeons operated in street clothes without anesthesia, and infectious diseases such as typhoid and cholera were thought to arise by spontaneous generation. Physicians were often highly educated. Like young William, many were taught at home; like William, they had read the classics in Latin and Greek; and like William they had often learned French, Italian, and German.

At age sixteen William was sent to Paris, where he studied medicine for four years. Under the influence of the great clinician and epidemiologist Pierre Charles Louis, he learned to distinguish typhoid from typhus and recognize it, less so in the living than by viewing their inflamed ulcerated Peyer’s patches at autopsy. He also met Pierre Bretonneau, who believed that “morbid seeds” spread disease from one person to another, maintained that cholera was a communicable disease, and objected to cholera patients being admitted to the general medical wards.

After leaving Paris, Budd went to Edinburgh. In 1839 he obtained his MD degree with a thesis on “acute rheumatism.” During his brief work as a naval surgeon, he was stricken with typhoid fever and almost died. Returning to his native village of North Taunton of 1,200 inhabitants in Devonshire, he went into general practice. In 1841, typhoid broke out in the village, and Budd observed that most of the afflicted had been in contact with another infected person. Later in his book he observed that “The first thing to arrest attention after the disorder had become rife in North Tawton was the strong tendency it showed, when once introduced into a family, to spread through the household.” He used this information in a medical competition for the Thackeray Prize in 1839, stating that the disease had a tendency to be communicable from one person to another, but was not successful.

In 1842, Budd set up a general practice in Bristol, the great city of commerce and industry in the west of England. The city was filled with crowded houses that had no decent drainage and frequently obtained their water supply from a single pump. The pump water was grossly contaminated by fecal discharges from the adjacent houses, leading to frequent outbreaks of diarrhea, typhoid, and cholera. Cognizant of the danger of contaminated water, Budd gave evidence before a parliamentary commission, and when the Bristol Waterworks Company was established in 1845, he was one of the original directors. In 1847 he was appointed to the Bristol Royal Infirmary and became a lecturer at the medical school. Put in charge of Bristol’s water supply, he instituted changes to clean it up about the same time that John Snow in London famously removed the Broad Street pump to prevent the spread of cholera.

In 1853 Budd recorded an outbreak of typhoid fever in the Welsh town of Cowbridge. Eight guests died after attending a wedding in which they had consumed lemonade made with water from a well located near the septic tank of the inn. Later, in 1866, he investigated an outbreak in which a man who contracted typhoid while traveling and infected all the inhabitants of a village. Beginning in 1856, he published a series of articles on the infectiousness of typhoid fever. He emphasized the importance of handwashing and general cleanliness, insisted that “all discharges from the body” be taken into vessels containing zinc chloride, and suggested that sewage be treated with carbolic acid or chlorine gas and that drinking water should be boiled. By 1866, deaths from cholera in Bristol had decreased from 2,000 in 1849 to twenty-nine in that year. In 1870 Budd was elected to the Royal Society, and the next year, he published his classic book Typhoid Fever: Its Nature, Mode of Spreading, and Prevention, which summarized the evidence for fecal-oral transmission of the disease in three propositions:

- That intestinal or typhoid fever is an essentially contagious fever.

- That the largest and most virulent part of the contagious principle is contained in the discharges from the diseased intestine of the fever patient.

- That the cloacae which filled the office of sewer, and which are universally acknowledged to be the principal agents in the dissemination for the disease owe this faculty solely to their being, in the ordinary course of events, the recipients of these discharges; and to the specific infection which they are thus constantly receiving.

In addition to his work on typhoid fever and cholera, William Budd also extended his studies to the contagious nature and prevention of diphtheria (1861), anthrax (1862), tuberculosis (1867), scarlet fever (1869), and diseases of cattle and sheep. He has been described by his biographer, Michael Dunnill, as Bristol’s most famous physician, genial, vivacious, ebullient; fond of good food, good wine, and female company. An enthusiast in his work, he could sometimes be seen running from his home to the infirmary to see more quickly how his patients were getting along. At age sixty-nine, he suffered a stroke that left him hemiplegic. He died six years later, in 1880, ironically the year when the typhoid bacillus, Salmonella typhi, was discovered. Along with John Snow, he remains one of the greatest epidemiologists of his time, an inspiration for the future generations that study the nature of diseases, epidemics, and ways of containing them.

References

- Dunnill MS. William Budd on cholera. International Journal of Epidemiology 2013:42:1576. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt205.

- Dunnill MS. William Budd: Bristol’s Most Famous Physician: Pioneer of Preventive Medicine and Epidemiology. Redcliffe; 2006.

- William Budd 1811 – 1880. Sue Young Histories. https://www.sueyounghistories.com/2010-04-15-william-budd-1811-1880/.

- Goodall EW. William Budd, a forgotten epidemiologist. Proc Roy Soc Med 1931:277.

- JHT (editorial). William Budd – general practitioner and epidemiologist. JAMA 1962;182:676.

- Morehead R. William Budd and typhoid fever. JR Soc Med 2000;95:564.

- ChatGPT consulted.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Spring 2023 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply