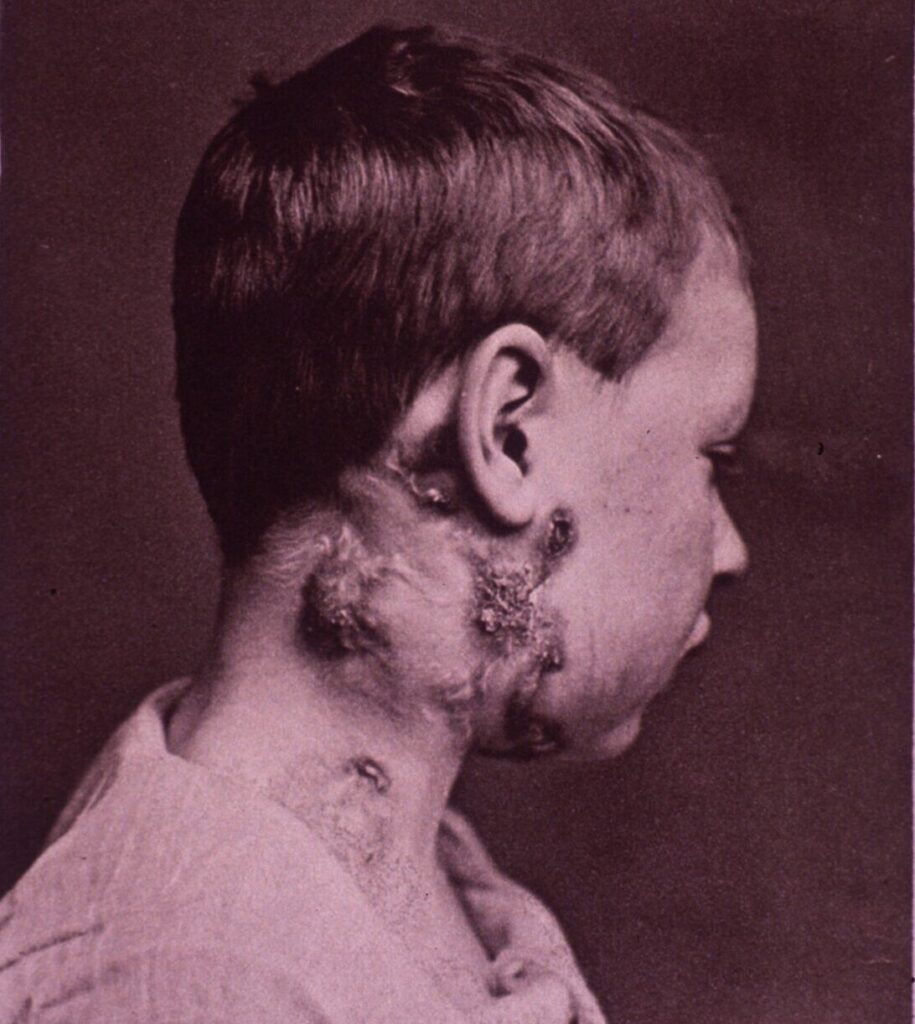

Scrofula, the old name for tuberculous lymphadenitis of neck, was once a common condition. The name was derived from the ancient Latin scrofa for sow, possibly because the affected nodes were shaped like the swollen neck of a sow or because pigs were particularly prone to the disease. The disease was also called struma, reflecting the patients’ enlarged neck.

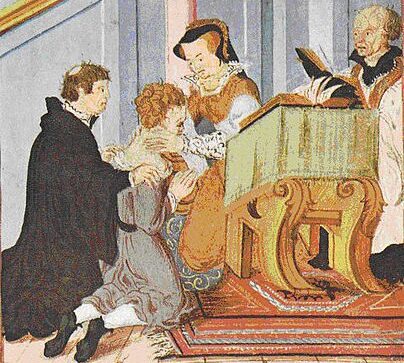

Scrofula has been known since antiquity. It was found in ancient Egypt, in a mummy of the 21st Dynasty (1070–946 BC). It became known as the King’s Evil (morbus regius or mal du roi) because in the Middle Ages kings were believed to be able to cure the sufferers by touching them and making the sign of the Cross. In France the practice of goes back to King Clovis (466–511) and reaffirmed during the Capetian kings. In Britain the first recorded healing of scrofula was during the reign of Edward the Confessor (1042–66). In Macbeth, King Edward is said to cure “all swoln and ulcerous, pitiful to the eye, the mere despair of surgery… by hanging a golden stamp about their necks.”

For many centuries the ritual was retained because it served to prop up royal authority and confirm divine favor, so much so that the authorities made efforts to stamp out competing folk healers. Even the blood of king was thought to have healing powers, such that of Charles I after his beheading. During their reigns, English and French kings touched thousands of their subjects and continued do so until Louis XVI and Queen Anne. The practice even spread to the New World, where the colonial governor of Virginia, Sir William Berkeley, still touched sufferers. One of the last to be (unsuccessfully) touched by Queen Anne was the renowned lexicographer and essayist Dr. Samuel Johnson (1709–1784), who suffered from scrofula at age two and had his eyes were severely damaged.

At various times scrofula was treated with purgatives, diuretics, bleeding of both arms, blistering of the skin with caustic agents, or the application of a plaster of goat’s dung and honey. Mercury was also widely used. Recommendations in the nineteenth century, were a Vegetable Pain Killer (probably opium in 70% alcohol), Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup (also opium), Sarsaparilla pills, Hood’s sarsparilla, extract of queen’s root, yellow dock, potassium and iron iodide, iodoform, dandelion, juniper berries, liver pills, acid phosphate mixtures, and cocaine. Surgery was thought to be too dangerous.

The cause of the disease was long unknown. It was attributed to an imbalance of the humors, to the glands filling up with phlegm, to a “vitreous degeneration,” or to a “primary obliteration of blood vessels.” As late as 1870 people speculated that it was a “constitutional defect” present in everybody but that a few were unable to correct or resist it. The relation to tuberculosis remained unclear until 1882 when Robert Koch identified the tuberculosis bacterium, an achievement for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1905.

Several kinds of tubercle bacilli may cause the disease. In 95% of cases the offending organism is Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Other mycobacteria may play a role in immunocompromised patients. Infection may occur through droplets, from milk, by hematogenous or lymphatic dissemination of pulmonary TB, or rarely through primary involvement of adenoids or tonsils. Diagnosis is nowadays made by fine needle aspiration or by biopsy.

Until the advent of streptomycin in the late 1940s, treatment was ineffective and often consisted of exposure to fresh mountain air and sunshine, a sojourn in a sanatorium, or taking the waters at spas. Surgical removal of the affected nodes was recommended in resistant cases. Nowadays treatment regimens are constantly changing, but consist of cocktail-drug treatments containing rifampicin along with pyrazinamide, isoniazid, ethambutol, and streptomycin. Scrofula has now become rare in most parts of the world. It is still prevalent in some developing countries and is more commonly seen in immunosuppressed patients such as in HIV.

Further reading

- Grzybowski S and Allen EA. Lancet 1995;346:1472.

- Turrell JF. The Ritual of Royal Healing in Early Modern England: Scrofula, Liturgy, and Politics. Anglican and Episcopal History 1999;68(1):3.

- Estes JW. The Pharmacology of Nineteenth Century Medicine. Pharmacy in History 1988;30(1).

- Barlow F. The King’s Evil. English Historical Review 1980.

- Landis HRM. The disappearance of scrofula. American Review of Tuberculosis; 21.

- Bhandari J, Thada PK. Scrofula. Study Guide from StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island 1904:Jun 2020.

Leave a Reply