Hina Haq

Cayon, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Caribbean

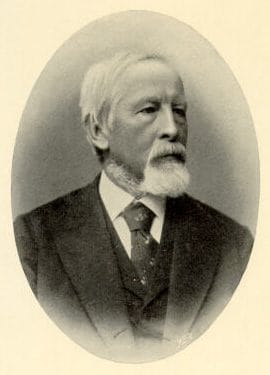

Adolph Kussmaul was born in Graben, Germany in 1822.1 He came from a long line of physicians and grew up in a beautiful place where miles of lush vegetation stretched out to nurture crops and create homes for pasture.2 Although he was born into privilege, he had to face adversity and many setbacks on the way to becoming a respected and accomplished physician.

After completing his medical education at the University of Heidelberg, he served as army physician in the Prussian war against Denmark.3 The experience was harrowing. Every minute of the day he heard cries of anguish, saw more dead bodies than he could count, smelled the stench of decaying corpses, and heard bombs falling. He amputated limbs and saved lives. He worked during a cholera outbreak, leaving no soldier untreated,2 and received high credit for ending the long-standing practice of letting soldiers bleed to death on the battlefield.3

His subsequent career was marred by ill health. In 1853, he was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré Syndrome, which affected his bladder, paralyzed his legs, and caused cardiac complications.2 Recovery was slow, and years would pass before he could use his legs normally, which meant that riding on a horse would prove difficult. In the nineteenth century, doctors used horses and rode them at neck-breaking pace to reach patients on time. When this realization dawned on him, he pivoted his career plans from being a general practitioner to pursuing a career in academia.4

Despite these setbacks, his years in academia proved fruitful. He described an abnormal breathing pattern in diabetic patients (“Kussmaul breathing”) and a form of paradoxical jugular vein distension (“Kussmaul sign”).5 He characterized a range of illnesses such as progressive bulbar paralysis, selective mutism, dyslexia (which he called “word blindness”),1 polyarteritis nodosa,3 and he coined the term “poliomyelitis.”6 He was the first to diagnose mesenteric emboli1 and the first to apply thoracocentesis2 and gastric lavage.5 He is also credited with the invention of the ophthalmoscope7 and gastroscope.8

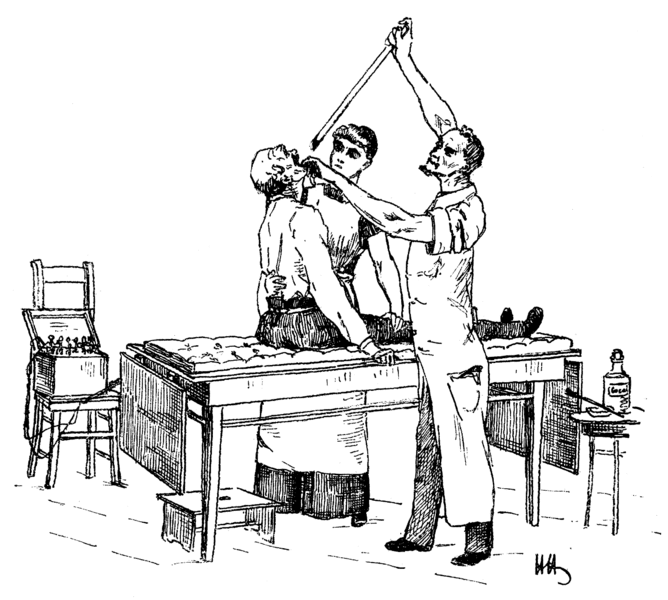

Adolph Kussmaul gastroscope presentation c. 1896. Via Wikimedia.

Kussmaul was familiar with the work of a Parisian urologist, Desormeaux, who developed the first endoscopic device. Kussmaul decided to apply a similar technique to visualize a tumor in his patient’s throat. He modified the design by adding a nine-inch-long straight tube. However, he faced resistance traversing the esophagus. Disheartened, Kussmaul halted his experiment indefinitely. It was not until he saw a sword swallower named “The Iron Henry” at the circus relax his neck muscles and straighten his esophagus to swallow a sword that he asked to try his gastroscope device on the entertainer. This time he inserted an 18.5-inch tube into the entertainer’s throat, resulting in the first endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract in 1868.8

Kussmaul experienced much grief during his life. At the height of his academic career, he lost his two young boys, one dying from tetanus and the second from drowning in the river.1 Yet he continued to publish many more case reports and ideas in journals, never permitting his personal problems to affect his goal of understanding and advancing medicine.

Adolph Kussmaul was awarded honorary citizenship of Heidelberg and was appointed the Badian privy councillor during the later years of his life.6 He retired in 1886 and died in 1902.3 It is through his dedication that we have a method to visualize disorders, possess therapeutic procedures, and to understand the pathophysiology of many diseases. He accomplished all this and much more while overcoming some of life’s most difficult obstacles. His intellectual curiosity and innovative streak was the gift Kussmaul gave us as his legacy.

References

- Loriaux, D. Lynn. “Adolf Kussmaul.” The Endocrinologist 2010;20(3):95. https://doi.org/10.1097/ten.0b013e3181e1e558.

- Bast, Theodore. “The Life and Time of Adolf Kussmaul.” The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 1927;173(3):424. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000441-192703000-00026.

- Matteson, Eric. “History of Vasculitis: The Life and Work of Adolf Kussmaul.” Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2012;79(11 suppl 3). https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.79.s3.12.

- Rehnberg, Victor, and Ed Walters. “The Life and Work of Adolph Kussmaul 1822–1902: ‘Sword Swallowers in Modern Medicine.’” Journal of the Intensive Care Society 2016;18(1):71-2. https://doi.org/10.1177/1751143716676822.

- Johnson, SK, RK Naidu, RC Ostopowicz, DR Kumar, S Bhupathi, JJ Mazza, and SH Yale. “Adolf Kussmaul: Distinguished Clinician and Medical Pioneer.” Clinical Medicine & Research 2009;7(3):107-12. https://doi.org/10.3121/cmr.2009.850.

- Khor, Sam, Mike Cadogan. “Adolph Kussmaul.” Life in the Fastlane. July 25, 2022. https://litfl.com/adolph-kussmaul/.

- Mark, HH. “The First Ophthalmoscope? Adolf Kussmaul 1845.” Archives of Ophthalmology 1970;84(4): 520-1. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1970.00990040522024.

- Staff, Proto. “Into the Depths.” Proto Magazine. September 1, 2021. https://protomag.com/technology/depths/.

HINA HAQ is a fourth-year medical student at Windsor University School of Medicine. Her interests lie in medicine. In her free time, she loves to go skydiving and listen to true crime podcasts.

Submitted for the 2022–23 Medical Student Essay Contest