Brendan Pulsifer

Atlanta, Georgia

Tuberculosis pervaded nineteenth-century American life like no other disease. More commonly known as consumption at the time, it was responsible for one in five deaths, making it the deadliest pathogen for people across ages, genders, and classes. Doctors often described tuberculosis as the most dangerous illness in their clinical practice because of its gruesome and unstoppable progression. What started out as a light cough or shortness of breath transformed, sometimes gradually and sometimes overnight, into a severe, unrelenting cough with fever that drained the life from patients.1

Physicians were terrified of tuberculosis largely because of their powerlessness to treat it. Before German microbiologist Robert Koch linked tuberculosis to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in 1882, the medical community had incorrectly cleaved to the miasma theory of disease, which held that noxious, foul smells caused illnesses.2 Without a clear understanding of its etiology, physicians could not standardize a treatment for tuberculosis. Instead, advertisements flooded local newspapers promoting experimental tonics, surgical procedures, and magical elixirs, each one claiming to have found the cure for consumption at last. “Dr. Schneck’s pulmonic syrup will cure every case of consumption,” read one notice in the Lowell Daily Citizen.3 “No remedy for consumption and consumptive diseases has ever been found that will at all compare with [Dr. Churchill’s elixir]” proclaimed another in the Sandusky Register.4 Many consumptives put stock in the healing power of these medicines, but few if any actually found relief from their suffering.

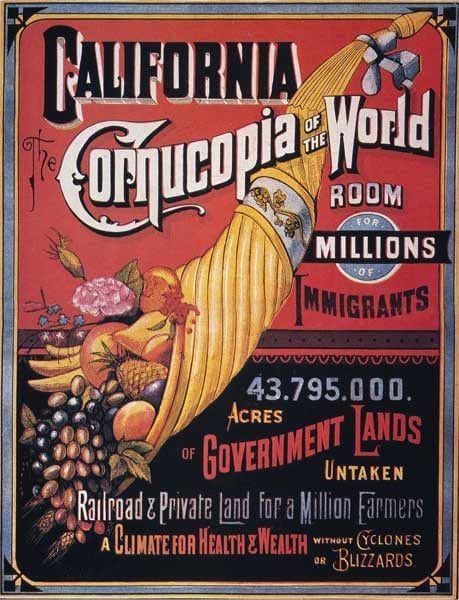

Without a widely accepted treatment regimen for tuberculosis, early nineteenth-century physicians began to endorse a new, unorthodox treatment for their patients: the “climate cure.” Its logic was simple—since tuberculosis primarily afflicted urban dwellers in cold environments who spent most of their time indoors, consumptives could restore their health by escaping their insalubrious setting. Sickly, crowded cities could not offer the same therapeutic benefits as the hearty, spacious prairie, which was expanding with the country’s frontier.5 Thus, lacking more immediate medicinal tools at their disposal, many physicians recommended the climate cure, hoping that outdoor living in a “healthful” climate would do what medicine could not.6

For many, the prescription worked, and enthusiastic former consumptives began to give the movement a national platform. Dr. Josiah Gregg published one of the first autobiographical accounts of his experience with the climate cure in his 1844 Commerce of the Prairies. In the narrative, he describes how his physicians, unable to find a better treatment for his consumption, advised him to take a trip across the prairie to cure his consumption. He joined a caravan headed for Santa Fe, and within weeks of arriving at his destination, he was completely cured. “The salubrity of the climate is most interesting,” he wrote. “New Mexico has experienced very little disease of a febrile character.”7 Commerce of the Prairies gained popularity throughout the country after its release and even was translated into French and German as consumptives from around the world became fascinated with the allure of the therapeutic frontier.

Gregg’s account helped inspire others to make health-based pilgrimages to the West. In 1847, famous British explorer George Ruxton visited the Rocky Mountains with two friends afflicted by tuberculosis and gave a ringing endorsement of the climate cure to the press that covered his trip. His companions, who had been “pronounced by eminent practitioners as perfectly hopeless,” were “restored to comparative sound health by a sojourn in the pure and bracing air of the Rocky Mountains.”8 Explorer and future presidential candidate John C. Fremont also led highly publicized explorations of the West in the 1840s. Each time, he reported the astounding effects of the climate cure: “The climate has been found very favorable to the restoration of health, particularly in cases of consumption.”9 Ruxton’s and Fremont’s celebrity endorsements of the climate cure helped to bring the practice of health-seeking to a national audience and built upon Gregg’s earlier work.

As the nineteenth century wore on, however, the appeal of the climate cure began to fade. The rise of the sanatorium posed one of the first challenges for proponents of western migration. Physician, scientist, and former consumptive Edward Trudeau believed that invalids needed rest, nutrition, and fresh air to combat tuberculosis and knew that not all patients afflicted with a debilitating illness could manage a thousand-mile journey. He established the first sanatorium in the US at his Saranac Lake cottage in the Adirondacks in 1885 as an alternative. Its emphasis on physician-mediated relaxation in a natural environment restored a number of patients back to full health. Excitement around the sanatorium grew quickly; by 1925, America boasted over 500 sanatoria for consumptives. Yet Trudeau’s closed institutional model forced health seekers to question the significance of the regional environment to their recovery. Tuberculosis sufferers who could receive adequate treatment close to home had little incentive to make an arduous sojourn to the frontier.10

Scientists also began to scrutinize the climate cure more thoroughly. Building on Koch’s discoveries, many medical researchers sought to better understand the relationship between climate and health on the microscopic level. Through their inquiries, they concluded that little scientific evidence could support the notion that a regional environment could directly influence an individual’s health. Harvard’s first professor of climatology, Robert D. Ward, published a 1921 report highlighting inconsistencies in the climate cure’s logic. “The older views concerning the predominant and direct influence of climate have largely been replaced by the conviction that good hygiene is more important than climate alone,” and that “a change of residence, habits, occupation, food, is usually of as much importance as, if not more importance than, the actual change in atmospheric conditions.”11 Moreover, his report suggests that physicians who prescribed the climate cure may actually harm their patients by sending them to unsuitable locations lacking adequate medical infrastructure. By the turn of the century, the scientific and medical communities viewed health-seeking as a tool of the past.12

For the time in which it held weight, however, the climate cure represented a preeminent, albeit unreliable, method for treating disease at a time when no other remedy could grant patients relief. Physicians of the early nineteenth century held equivocal notions about the cause of infectious disease, but they recognized that consumptives traveling west could find respite on the prairie that they could not provide at home. For them, and for many of their patients, the best hope lay in the frontier.

End notes

- Sheila M. Rothman, Living in the Shadow of Death: Tuberculosis and the Social Experience of Illness in American History (New York: BasicBooks, 1994), 1.

- Nancy Tomes, The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women, and the Microbe in American Life (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 28.

- “Scheck’s Pulmonic Syrup for the Cure of Consumption, Coughs, and Colds,” Lowell Daily Herald, November 18, 1876. America’s Historical Newspapers (Readex).

- “The Great Remedy for Consumption,” Sandusky Register, August 21, 1860. America’s Historical Newspapers (Readex).

- Gregg Mitman, “In Search of Health: Landscape and Disease in American Environmental History,” Environmental History 10, no. 2 (2005): 197.

- Jeanne Abrams, “On the Road Again: Consumptives Traveling for Health in the American West, 1840–1925,” Great Plains Quarterly 30, no. 4 (2010): 272.

- Josiah Gregg, Commerce of the Prairies, (Chicago: Lakeside Press, 1844), 140.

- George Ruxton, Ruxton of the Rockies, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1950), 269.

- John C. Fremont, Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1842, and to Oregon and North California in the Years 1843-44, (Washington, DC: Gates and Seaton, 1845), 49.

- Gregg Mitman, “Geographies of Hope: Mining the Frontiers of Health in Denver and Beyond, 1870-1965,” Osiris 19 (2004): 101.

- Robert D. Ward, “Climate and Health, With Special Reference to the United States,” The Scientific Monthly 12, no. 4 (1921): 355.

- Ward, “Climate and Health,” 375.

Bibliography

- Abrams, Jeanne. “On the Road Again: Consumptives Traveling for Health in the American West, 1840-1925.” Great Plains Quarterly 30, no. 4 (2010): 272.

- Fremont, John C. Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1842, and to Oregon and North California in the Years 1843-44. Washington, DC: Gates and Seaton. 1845.

- “The Great Remedy for Consumption.” Sandusky Register. August 21, 1860. America’s Historical Newspapers (Readex).

- Gregg, Josiah. Commerce of the Prairies. Chicago: Lakeside Press. 1844.

- Mitman, Gregg. “In Search of Health: Landscape and Disease in American Environmental History.” Environmental History 10, no. 2 (2005): 197.

- Rothman, Sheila M. Living in the Shadow of Death: Tuberculosis and the Social Experience of Illness in American History. New York: BasicBooks. 1990.

- Ruxton, George. Ruxton of the Rockies. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 1950.

- “Scheck’s Pulmonic Syrup for the Cure of Consumption, Coughs, and Colds.” Lowell Daily Herald. November 18, 1876. America’s Historical Newspapers (Readex).

- Tomes, Nancy. The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women, and the Microbe in American Life. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1998.

- Ward, Robert. “Climate and Health, With Special Reference to the United States.” The Scientific Monthly 12, no. 4 (1921): 355-375.

BRENDAN PULSIFER is a first year medical student at Emory University School of Medicine. He completed his undergraduate degree in biochemistry at Bowdoin College in 2020 and served as an AmeriCorps fellow in Washington, DC post graduation. He plans to continue combating social inequalities in the distribution and outcome of disease through research and clinical practice, with the ultimate goal of creating more structurally competent healthcare systems in the United States and abroad.

Submitted for the 2022–23 Medical Student Essay Contest