James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

| A solitary Steller’s Sea eagle near the bank of the Zhupanova River on the eastern shore of the Kamchatka peninsula. Unless otherwise specified, all photos by author. |

The Steller’s Sea eagle (Haliaeetus pelagicus) handily outsizes the national bird of the United States, the Bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). Steller’s Sea eagle is the heaviest eagle in the world: females weigh from thirteen to twenty pounds and males weigh between eleven and fifteen pounds. Its seven-foot wingspan is the largest of any living eagle. These magnificent birds of prey feed mainly on fish, subsisting mainly on salmon, plentiful throughout their range in the northern Pacific. The Kamchatka Peninsula is home to 4,000 of these eagles. The Prussian naturalist Peter Simon Pallas (1741–1811) first described the species, naming it Haliaeetus pelagica. Its official name, “Steller’s Sea eagle,” has been designated by the International Ornithologists’ Union.

The natural world is replete with Steller’s children. Among the vertebrates we find Steller’s Albatross, Steller’s Eider, Steller’s Jay, Steller’s Sculpin, Steller’s Sea cow (now extinct), Steller’s Sea lion (northern sea lion). Among the invertebrates, Steller discovered a large mollusk known as the gumboot chiton—Cryptochiton stelleri. Nor has the botanical world forgotten our hero, usually preferring the Latin of Linnean classification: Alaska bellheather (Harrimanella stelleriana), Steller’s rockbrake (Cryptogramma stelleri), speedwell (Veronica stelleri), and Steller’s wormwood (Arteista stelleriana).1 The list goes on, but this should be enough for us to ask: “Who was Steller?”

Georg Wilhelm Steller, the man honored by this diverse taxonomy, was born in the town of Windsheim, near Nuremberg, Germany on March 10, 1709. He perished thirty-seven years later on November 14, 1746 in the remote town of Tyumen, just east of the Ural Mountains in Asiatic Russia. Steller was a physician, a naturalist, and an explorer. He made important contributions in the fields of botany, zoology, and ethnography of the Russian Far East. The state of Alaska recognizes him as their first physician and naturalist. Steller is credited for being the first ship’s physician to have successfully treated scurvy, antedating James Lind’s A Treatise on Scurvy published in Edinburgh in 1753. We really do not know what he looked like. He sat for no portrait and though he traveled for years with a good draftsman who aided him in his work, no personal sketches seem to exist. No accounts tell us if he was tall or short, slight or stout. Based on the challenges and hardships of travel and exploration he faced, he must have been a man of considerable physical stamina and endurance. His surviving travel journals tell us much about the opinions he held and his view of the world. He published no scientific reports of his findings during his lifetime. What survives of his work is found in the reports sent back to the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg while in the Russian Far East. It would be left to others to organize this material and incorporate it into their own publications. This process continues; even today, additional materials are discovered in the archives in St. Petersburg.

Georg Wilhelm Steller: Childhood and education

At his birth on Sunday, March 10, 1709 in the Lutheran city of Windsheim, it was reported that he was a lifeless child. The efforts of his mother’s sister miraculously revived him after the midwife had given up hope and departed. Biographer Ann Arnold notes that he was a Sonntagskind, a Sunday’s child, by legend “a being able to give the worst disaster a happy outcome.” His father was a Lutheran cantor named Johan Jakob Stöhler who changed the family name to Stöller in 1715. (Once in Russia, his son further changed it to Steller to facilitate pronunciation by Russian speakers.) At the age of five, he entered Windsheim Gymnasium where every subject was taught in Latin. He would put his mastery of the language to good use as a naturalist in the notes he compiled in the Russian Far East. His schooling was rigorous and we may infer he devoted himself to his studies, winning a scholarship at age fifteen to the highest level of his school in Windsheim. He cultivated his love of nature during holidays in the nearby Schoszbach Forest.2 In 1729, then twenty years old, he received a scholarship to study religion and medicine at the University of Wittenberg. The four days of travel to Wittenberg began a lifetime journey from home; he would never again see the town of his birth or his parents.

While in Wittenberg he took walking trips to Köthen, where his older brother Johann Augustin Stöller practiced medicine. Augustin exercised considerable influence on his decision to give up theology and pursue medicine and the natural sciences. Steller corresponded with his brother to the end of his life. In 1731 his scientific interests took him to the University of Halle. He enrolled in zoology courses given by the famous anatomist and zoologist Johann Friedrich Cassebohm (1698–1743), who had recently joined the faculty of medicine. Steller attended demonstrations in the anatomical theater performed on animals, as human cadavers were not available. He also studied botany with Professor Friedrich Hoffmann (1660–1742) who shared with Herman Boerhaave in Leyden the reputation of being the greatest medical luminary in all of Europe. It was at Halle that Steller’s fascination and flare for botany flourished, and within a year of his arrival, he began to teach his own classes in the subject.

The three years Steller spent in Halle culminated with a trip to Berlin in August 1734 to sit for the prestigious examinations of the Ober Collergium Medicum and the Collegium Medico-Churgicum. Dr. Michael Mathias Ludolf (1696–1756), professor of materia medica and botany at the University of Berlin, examined him and found him proficient enough to fill a professorial chair in botany. Steller found himself fully qualified for an academic position in a German university, yet no openings were available.

At the time, there were dwindling university positions available for the growing numbers of educated men in Germany. The newly formed Imperial Academy of Science in St. Petersburg offered additional opportunities for German graduates. The Academy had been established in 1724 by Peter the Great’s widow, Catherine the First, as one of her first acts of office. Encouraged by his mentor Friedrich Hoffmann to seek a position in St. Petersburg but lacking funds for the long voyage, Steller proceeded overland to Danzig. At the time, the city had been besieged by the Russian Army as one of the last events in the War of the Polish Succession, which ended in October 1735. The Russian army was suffering from a shortage of surgeons. One of the high-ranking Russian medical officers who was a protégé of Hoffmann welcomed Steller with open arms. He was attached to an artillery regiment caring for the sick and wounded until they could be returned to St. Petersburg by sea.

Steller arrived in St. Petersburg toward the end of November 1734 where he remained for the next four years. He made the acquaintance of the Swiss botanist Dr. Johann Amman (1707–1741) and helped design the Academy’s botanical garden and catalogue its herbarium. With Amman, he explored the countryside around St. Petersburg, collecting and studying plants of the area. He had access to the Academy’s superb library. The foundation of the library’s collection had been built by Peter the Great with books from his visits to Europe and also from his wars with Sweden and Poland. One volume Steller studied, Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, contained an illustration of a blue jay, dissimilar to any European species. The illustration would remain in his memory for almost a decade when, as a member of the Second Kamchatka Expedition, he encountered a similar bird that now bears his name: Steller’s Jay. It was this finding that convinced him that they had reached North America. To understand how Steller’s career would unfold, it is necessary to review the history of Russia’s great exploration of its Far East territories.

The First and Second Kamchatka Expeditions: 1725–1730 and 1733–1745

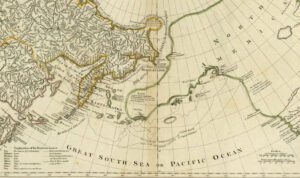

Even as Peter the Great lay on his death bed, he set in motion an ambitious expedition to explore and map Russia’s vast lands extending eastward from the Ural Mountains across Siberia to Kamchatka. Peter had succeeded in establishing peace with his European neighbors, and it was time to determine the extent of his empire. Whether the eastern expanse of Russia extended to North America was a burning issue that Peter wanted to settle. To command the expedition, he selected Fleet-Captain Vitus Bering (1681–1741). Bering, a Dane who was born in Horsens, Denmark-Norway, had enrolled in the Russian Navy in his early twenties and risen through the ranks. By January 24, 1725, the first part of the expedition left St. Petersburg. Four days later, Peter the Great died. It was Catherine the First who handed Bering his final instructions. The expedition, destined to be known as the First Kamchatka Expedition (1725–1730), traversed the entire expanse of Russia to the Pacific where two seaworthy vessels were constructed. Bering sailed into the strait that bears his name to 67°N latitude, concluding that Russia did not extend to North America. Returning to St. Petersburg in 1730, he met with authorities of the Academy of Sciences who were highly skeptical about his findings.

The Second Kamchatka Expedition (1733–1743) grew out of Bering’s immediate proposal to lead another mapping expedition to seek ocean trade routes to Japan and the separate continent that he believed lay east of Kamchatka. The plans drawn up for this expedition by the Admiralty in 1732 included a nautical survey and mapping of the northern coasts of Asia and of North America down to California. The Academy of Sciences matched these plans with elaborate goals in zoology, botany, ethnological, anthropological, linguistic, and historical surveys. Two vessels were to be built on the coast of the eastern wilderness to search for North America. A small army of soldiers and skilled laborers would be required to transport the expedition thousands of miles across Asiatic Russia to construct shipyards and establish iron mines and foundries necessary to build the ships. Travel across the vast expanse of the empire in the first half of the eighteenth century required caravans of sleighs in winter that could take advantage of frozen rivers. Overland travel in summer was difficult, but when the rivers became free of ice, it was possible to travel on barges constructed at strategic cities across the continent so as to move men and provisions downstream or towed upstream.

Steller joins the Second Kamchatka Expedition

In January 1737, Steller was accepted as part of the Kamchatkan Expedition as an adjunct in natural history at a salary of 600 rubles a year. Steller busied himself preparing for his journey, though little was available on Siberia in the library of the Academy of Sciences. Earlier in 1735, Steller had cultivated the friendship of Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt (1685–1735), who had studied medicine at the University of Halle under Hoffmann. Messerschmidt had spent seven years in Siberia collecting data and specimens on the geography, natural history, and ethnography of the region. Steller had learned as much as he could from him about Siberia over a three-month period before Messerschmidt’s death in March 1735. As Steller was in the midst of assembling equipment to leave for Kamchatka, he began to court Messerschmidt’s young widow, Brigitta Helena. Though she knew of her husband’s frightening experiences in the wilderness of Siberia, she agreed to marry Steller and accompany him on the expedition. On or about January 15, 1738, he departed for Moscow with his new wife and her daughter in a small caravan of sledges. This pleasant and efficient mode of travel brought them to Moscow on January 30, 1738. There his wife declared she had had enough of winter travel and would go no further. Thus ended any dreams Steller might have had of family life. Though he honorably attempted to provide for her, they would never be reunited. She continued to lay claim to his salary until his death. Nor did she remain a widow long, marrying shortly after official word of his death was made public.

Travels in Siberia

The difficulties of travel were such that it took Steller three years to reach Okhotsk on the eastern coast of Siberia. From Okhotsk he proceeded by sea to Kamchatka to join the Second Kamchatka Expedition. Though he kept a tagebuch, a day book, recording his journey across Siberia, unfortunately it has been lost. Steller’s biographer, Leonhard Stejneger, noting the rich detail in the surviving journal of Steller’s sea voyage to America, surmises that his travel notes would have provided a valuable glimpse into the travails of travel, the topography, and the natural history of Siberia in the eighteenth century. However, even without the journal, Stejneger was able to reconstruct an in-depth account of Steller’s travel to the Russian Far East.

Bering and the voyage to America

|

| Avacha Bay: Port of Petropavlosk, Kamchatka, Russia. 2017. |

Three years after departing St. Petersburg, in February 1741, Steller first met with Captain Commander Vitus Bering at his headquarters in the settlement of Petropavlovsk (St. Peter and Paul) in Avacha Bay. The entrance to the harbor is located near the tip of the Kamchatka peninsula on its eastern shore. The author visited the Kamchatka Peninsula, Avacha Bay, and the port of Petropavlovsk in 2017, almost 300 years after Steller met with Bering. It remains one of the world’s most magnificent natural harbors: eleven miles in diameter with a uniform depth, no dangerous reefs or sunken rocks, and a narrow, well-protected entrance. Glacier-covered mountains surround the harbor with intermittent plumes of smoke rising into the sky as evidence of continued volcanic activity. Avacha Bay most certainly provided Steller with a scene of unsurpassed beauty.

Bering was in the midst of preparations for the voyage to America. He was sixty years old and had devoted the last fifteen years of his life to travel in the Russian Far East. At this point in his preparations, his chief surgeon was ill and had requested to be sent back to St. Petersburg, leaving him with an assistant surgeon and a surgeon’s apprentice. Steller was just the man he wanted: he was a physician, his knowledge as a naturalist satisfied the aims of the expedition, and he was a Lutheran theologian (Bering’s faith and that of several of the officers). Bering did Steller the honor of inviting him to share his cabin. For his part, Steller was to have the services of Friedrich Plenisner, an artist and surveyor.

The voyage to America had to wait until the ice in the harbor began to break up. The two ships that made up the expedition had been built from scratch in Okhotsk on the eastern coast of Siberia. The flagship, the St. Peter, under the command of Bering, and the St. Paul, commanded by Captain A.I. Chirikov, finally set sail on June 4, 1741. On the twentieth of June, the ships encountered bad weather with thick fog and lost contact. For four days the St. Peter searched in vain for the St. Paul.3 The two vessels never saw each other again. Bering was forced to continue alone in a northeasterly direction. They were at sea for six weeks without sighting land when on July 15, 1741, Steller, who spent his days continually on deck, suddenly got a brief glimpse of land. He was universally disbelieved, but the next day, suddenly at noon, the clouds lifted and the sun revealed a magnificent panorama of “high, snow-covered mountains.” A single volcanic peak rose out of the sea to a point higher than any mountain they had seen. They were viewing what is today St. Elias Mountain Range, the highest coastal mountain range on earth.4 They had discovered North America and what would become Alaska. Steller regarded this as the culmination of the ten-year Kamchatka Expedition.

The St. Peter was dangerously low on drinking water, and it was necessary to land and resupply. They chose a large island close to the mainland of Alaska. Several more days of tacking close to the island were required to find a safe anchorage; they named the island St. Elias after the saint commemorated on the day they came ashore. It is known today as Kayak Island while its southern cape retains the name St. Elias. Bering’s first order was to send a party ashore in a longboat to obtain water. Steller was in a frenzy to be allowed ashore. A heated argument erupted between Steller and Bering, who did not want Steller to go ashore. Bering was anxious to start the return journey, fearing rough seas as it was already late in the season. To his credit, overlooking Steller’s rude behavior, the Dane relented and gave his short-tempered naturalist ten hours to explore the island with his hunter, Thoma Lepikhin.5 Bering did not let him off without a quid pro quo. When Steller departed the ship for the island, Bering gave him a grand send-off by having the ship’s trumpeters “come to the rail and sound a noisy flourish as for a naval dignitary.”6

|

| Steller’s Jay (Cyanocitta stelleri). Photo by Noel Reynolds on Flickr. CC BY 2.0. |

During his exploration of the island, Steller was able to describe 144 plants, recording his findings in Latin. He returned with a singular specimen. To quote Steller: “I remembered to have seen a likeness painted in lively colors and described in the newest account of the birds and plants of the Carolinas published in French and English.” This was the volume he had seen in the Academy Library in St. Petersburg. Seeing a similar bird, the “blue Jay” as the author called it, allowed Steller to draw the conclusion that they were in North America. In 1788, the naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin (1748–1804) in appreciation of Steller’s discovery gave the bird its scientific name Cyanocitta stelleri. Steller’s Jay immortalized the name of Alaska’s first ornithologist.

Steller also discovered the presence of human habitation on the island. A short distance into the forest, they found a log that had been dug out and recently used for cooking. Bones and meat were scattered around the area indicating a precipitous departure. They found a cellar full of provisions for winter, hunting weapons, and fishing gear. Steller’s knowledge of Kamchadal methods of food preparation led him to the conclusion that the inhabitants had originally come from Kamchatka and were of the Ugalakmuit tribe.7 At Steller’s suggestion, Bering had gifts sent back to the island to replace those taken from the native’s cellar including an iron kettle, a pound of tobacco, a Chinese pipe, and Chinese silk.

Fifty years after Bering’s expedition landed on Kayak Island, this account was confirmed by the Billings-Sarychev Expedition (1789–1795) sent to explore the status of fur-bearing animals in Russia’s possessions in North America. An elderly Chugach man came aboard the ship and told Sarychev his recollections of a ship that anchored off the island. The ship had sent a boat ashore and the natives ran away. After the ship departed, the natives returned to the subterranean storeroom and found the glass beads, leaves of tobacco, an iron kettle, and a few other items.8

Returning to Kamchatka: Shipwreck

|

| Monument to Vitus Bering (1681–1741). Bering Island, Russia. |

The St. Peter began its return journey to Avacha Bay on July 21, 1741. For the next two months, they were beset by a series of tremendous storms and threatening seas. Increasingly, members of the crew were incapacitated by scurvy or died of the disease. Their water supply was depleted and for days meals could not be cooked. Barely enough men were fit to stand watch and manage the ship. Because the sun was infrequently seen, accurate navigation was impossible; the ship’s logs that survived are in conflict as to their exact course as they struggled through the Aleutian Islands.

On November 5, they sighted land but could not be certain as to their location. Was it the coast of Kamchatka or an island off the coast? Bering, now incapacitated and confined to bed, believed they had reached Kamchatka and wanted to proceed to Avacha Harbor, but they were down to six barrels of bad water and barely enough men to handle the ship. Nature solved the issue, as the St. Peter was driven toward a reef, and just when destruction appeared inevitable, a huge wave suddenly lifted the vessel over the reef into quiet water. A few days later, a severe gale washed the ship ashore, badly damaging the hull and rudder. They soon discovered they were on an uninhabited island that today bears the Captain-Commander’s name, Bering Island. It is one the Commander Islands, the westernmost group of islands in the Aleutian chain that hang like a necklace below the Bering Sea between Alaska and the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Bering Island, shaped like a human sternum or blade, points in a southeasterly direction. It lies 125 miles off the coast of Kamchatka and is fifty-six miles long and fifteen miles wide. The author visited Bering Island in the summer of 2017, and while no longer uninhabited, it is sparsely populated and largely as it was in the winter of 1741–1742 when the St. Peter was shipwrecked. Today the inhabitants are largely concentrated in the fishing village of Nikolskoye, located on the northwest corner of the island with a population of approximately 700 of Aleut ancestry who were relocated to the island during the eighteenth century. The local museum features a skeleton of Steller’s Sea cow and nearby is a memorial monument to Vitus Bering. Two-thirds of the way down the eastern side of the island is the site where the St. Peter was shipwrecked, known today as Commander Bay. It was here the survivors would spend the next nine months enduring a dark Arctic winter and living off the land. Today there is a nature reserve with a small monument at the site of the graves of Bering and the men of the St. Peter who perished on the island.9 Rock ptarmigan, the bird that first sustained Steller and the crew of the St. Peter with fresh meat, can still be spotted. Arctic blue foxes that tormented the castaways still patrol the beach.

|

|

|

Photographed at Commander Bay, Bering Island, 2017. |

|

Bering and several members of the crew who were seriously ill with scurvy had to be carried ashore and were placed on the beach with minimal protection from the elements. Steller attended to the sick as best he could, but Bering died on December 8, 1741, along with fourteen additional crew members who perished during their stay.

During their time on the island, Steller used his knowledge of botany to collect native plants in an attempt to cure and prevent further outbreaks of scurvy. While at sea, the Russian naval officers refused to listen to his opinions or heed his dietary advice. His success in treating scurvy and restoring the health of the survivors reversed this situation. In his role as the ship’s surgeon, he sustained the morale of the crew and motivated them to rebuild the St. Peter. He used his time on the island by making a thorough study of its natural history. The animal species he studied include: the Steller Sea eagle, the flightless spectacled cormorant, the Steller Sea otter, the northern fur seal or “sea bear,” and Steller’s Sea lion. The most notable of his discoveries was a large and abundant sea animal inhabitating the shallow waters around the island.

The Steller Sea cow

|

| Illustration of the Steller Sea cow. Aleut Museum of Local Lore, Bering Island. |

This animal, aptly named Steller’s Sea cow, would be hunted to extinction within a few decades of the crew’s departure. Steller’s Sea cow is a member of the order Sirenia, which comprise several distinct families that include the familiar manatee found today in Florida’s coastal waters. They are fully aquatic mammals adapted to the cold Arctic waters of the North Pacific and feed on kelp in shallow coastal waters. Steller made a thorough study of the species, observing their feeding and social habits, recording the anatomical findings of dissection, and estimating their weight at twenty tons. His observations of avian and botanical species on the island were added to the sixty-page monograph he wrote in Latin, De Bestiis Marinis (The Beasts of the Sea), which was published posthumously under his name by the St. Petersburg Academy in 1751.

With the passing of winter and the health of the crew restored, they began to rebuild the St. Peter. Using timber and material from the wreck, by this time buried deep in the sand, they had to construct an entirely new vessel that would be sea-worthy enough to carry them across open water to Kamchatka. Space was at a premium on this second iteration of the St. Peter even though thirty-two of the original seventy-eight men had perished. While the sailors used their allotment of space for the precious sea otter pelts they collected, Steller used his space for manuscripts and specimens. Still, there was not enough room and Steller had to leave behind a significant part of his collection. It was not until August 14, 1742, over nine months after being shipwrecked, that they were able to depart. Crossing 100 kilometers of ocean, they entered Avacha Bay two weeks later.

Final years, 1742–1746: Kamchatka and Siberia

Steller spent his remaining years exploring the Kamchatka Peninsula and the Russian Far East. He continued to investigate the natural world and extended his ethnographic observations of the Itelmen peoples of the region. In an ugly incident, his known sympathies for the local inhabitants led to false accusations of fomenting a rebellion and his arrest. He was forced to stand trial but was acquitted. Having been released from custody, he departed by sleigh in an attempt to return to St. Petersburg. It was on this journey he contracted a severe fever. Rather than stopping to recover, he continued to travel, reaching Tyumen on November 12, 1746. Although two German doctors were present at the time to comfort him, he perished. As a Protestant, he could not be buried in the consecrated ground of Tyumen’s Russian Orthodox cemetery. “A visiting Lutheran minister wrapped Steller’s body on his own red mantle and performed the burial service on a bluff overlooking the Tura River. That night, grave robbers unearthed the corpse and stealing the precious religious garment left the body as prey.”10

Legacy

News of Steller’s death reached the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg on December 8, 1746. Not long afterward, news of the death “of the famous botanist” spread to Europe, appearing in the Gazette d’Amsterdam on January 25, 1747 and also reaching his brother, Augustin. Steller’s observations on the natural history and ethnography of the Russian Far East survive because he was able to pack and dispatch them to the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg before his death. These materials appeared in publication during the second half of the eighteenth century in the works of other naturalists. Johann Georg Gmelin’s four-volume Flora Sibirica incorporates Steller’s plant observations, Stepan Petrovich Krasheninnikov’s Explorations of Kamchatka, and other material from Steller’s notebooks. In 1774, Steller’s History of Kamchatka and in 1793, Steller’s journal on the St. Peter both appeared in German. Steller’s Journal of a Voyage with Bering, 1741-1742 and Steller’s History of Kamchatka are available in excellent English translations.11 The later volume establishes his credentials as an ethnographer.

Robert Huxley, the editor of The Great Naturalists (a collection of essays by distinguished historians), numbers Georg Wilhelm Steller among the naturalists of the Enlightenment.12 By the standards of today, Steller’s medical education was rudimentary, with a heavy emphasis on the medicinal properties of plants. From the indigenous peoples of the Kamchatka Peninsula, he studied dietary habits and learned which plants allowed them to survive the Arctic winter free from symptoms of scurvy. He used this knowledge to treat and prevent scurvy and is credited with being the first physician to have done so. Leonard Stejneger’s biography Georg Wilhelm Steller, while somewhat difficult to come by, will reward the reader with a rich tale of travel and adventure in the vast Russian Far East as Steller’s life played out against the panorama of Russian history.

End notes

- Ann Arnold, Sea Cows, Shamans, and Scurvy: Alaska’s First Naturalist: Georg Wilhelm Steller, Frances Foster Books, Farrar Straus Giroux, New York, 2008. Appendix “Concordance for Animals and Plants Mentioned in Text” by Rudolf Schmid, University of California, Berkley, pp. 167-170.

- Leonhard Stejneger, Georg Wilhelm Steller: The Pioneer of Alaskan Natural History, Harvard University Press, 1936. See pages 14-18 for these details.

- On returning to Petropavlosk, Steller learned that the St. Paul had sailed on to America and returned to Avacha Bay on October 9, 1741. Twenty-one of the crew succumbed to scurvy, and twelve men who were sent ashore to replenish the water supplies were lost. Over-wintering in Petropavlosk in the spring of 1742, Tchirikov started out again in search of Bering but failed to find him. He returned to Petropavlosk on July 1, 1742, and a month later returned to Okhotsk.

- Orcutt Frost, Bering: The Russian Discovery of America, Tale University Press, 2003, p. 144.

- Steller did his fieldwork with the help of a draftsman to illustrate specimens and a hunter to shoot and prepare birds and animals for further study.

- Leonhard Stejneger, Georg Wilhelm Steller, p. 266.

- Corey Ford, Where the Sea Breaks Its Back: The Epic Story of Georg Steller and the Russian Exploration of Alaska, Alaska Northwest Books, 1966.

- Dean Littlepage, Steller’s Island: Adventures of a Pioneer Naturalist in Alaska, The Mountaineers Books 2006, p. 203.

- In 1991 Orla Madsen of the Historical Museum of Norsens, Denmark led an archeologic expedition to excavate Bering’s grave. They found six graves, including a skull believed to be that of Vitus Bering.

- This account appears in both Stejneger’s biography, Georg Wilhelm Steller, and Ann Arnold’s Sea Cows, Shamans, and Scurvy cited above.

- Georg Wilhelm Steller, Journal of a Voyage with Bering, 1741-1742, edited with an introduction by O. W. Frost, Stanford University Press, 1988; Georg Steller, Steller’s History of Kamchatka, translated by Margarit Engel and Karen Willmore, University of Alaska Press, 2003.

- The Great Naturalists, edited by Robert Huxley, “Georg Steller: The Discover of Alaska (1709-1746),” Thames & Hudson, 2007.

JAMES L. FRANKLIN is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 15, Issue 2 – Spring 2023

Winter 2023 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply