Anthony Trollope is one of the few popular British novelists of the nineteenth century who is still widely read. He wrote some forty novels, notably the Palliser series about parliamentarian politics, and the Barchester stories with their intrigues in the established Church of England and featuring the lovable warden Mr. Harding and the shrewish Mrs. Proudie. Doctor Thorne is the third novel in the Barchester series. It has its fair share of intrigue, avarice, and romance, but is of particular interest here because it highlights the conflict between the city physicians and the more practical apothecaries who at that time still provided most medical services, especially in rural areas.

Doctor Thorne is a country apothecary who has graduated from an accredited medical school and is entitled by law to call himself a doctor. He is looked down upon by the city physicians, not in the least because he compounds his medicines in his shop by “putting together common powders for rural bowels, or spreading vulgar ointments for agricultural ailments.” He charges a mere seven and sixpence for a visit, unlike his city competitors who charge a guinea “without letting his left hand know what his right hand was doing . . . without a thought, without a look, without a move of the facial muscles . . . hardly . . . aware that the last friendly grasp of the hand had been made more precious by the touch of gold.”

Dr. Thorne still relies heavily on traditional methods such as herbal remedies and bloodletting. “He was brusque, authoritative, given to contradiction . . . and inclined to indulge in a sort of quiet raillery, which sometimes was not thoroughly understood. People did not always know whether he was laughing at them or with them; and some people were, perhaps, inclined to think that a doctor should not laugh at all when called in to act doctorially.” His rival physicians also claimed that apothecaries were always thinking about money, whereas they practiced “in a purely philosophical spirit,” and one regarded any gain as “an accidental adjunct to his station in life.”

But Dr. Thorne has a close relationship with some of the noble and wealthy families in his area. He is the confidant of the haughty Lady Arabella, who insists that her son must “marry money.” He advises her financially embarrassed husband on loans and mortgages. He is also the guardian of the humble young woman with whom Lady Arabella’s son is in love.

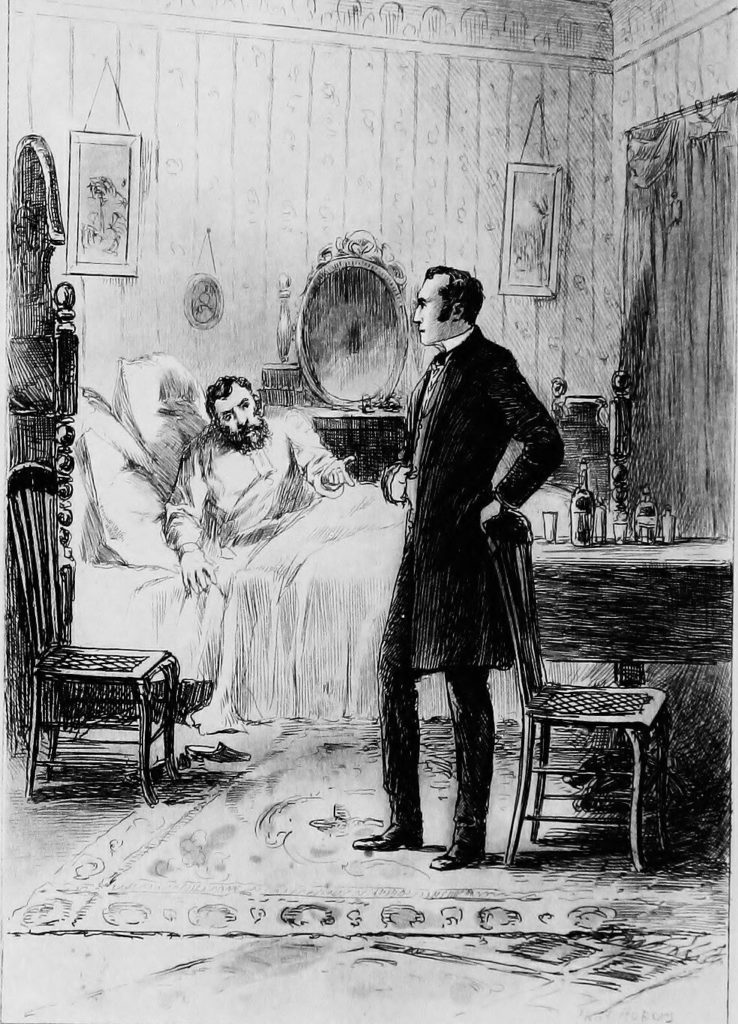

Dr. Thorne is also the medical attendant of the immensely wealthy squire Scatcherd, who is in the final stages of destroying his already much damaged liver with a bottle of brandy hidden under his bedsheets. His son and heir is engaged in the same destructive project. As his servant explains, “the master he do take a drop too much at times and then he has the horrors—what is it they call it? delicious beamends, or something of that sort.”

Trollope explains that he will not disgust his reader by describing the poor wretch in his misery: “the sunken, but yet glaring eyes; the emaciated cheeks; the fallen mouth; the parched, sore lips;” and “the face, now dry and hot, and then suddenly clammy with drops of perspiration; the shaking hand, and all but palsied limbs; and worse than this, the fearful mental efforts, and the struggles for drink; struggles to which it is often necessary to give way.”

When father and son die, their money goes up for grabs, and we will not disgust the reader, in Trollopian parlance, by revealing who gets the money or how the story ends. We merely suggest to the reader that he will derive great pleasure in reading the book.

Leave a Reply