Lloyd Klein

Eric Wittenberg

California, San Francisco, United States

|

| Contemporaneous photograph of the dwellings dug into the hills in Vicksburg to escape the bombardment. Public domain. |

The vital importance of controlling the Mississippi River was apparent to Union strategists from the beginning of the Civil War. The river served as a major supply route, facilitated the transportation of men and military supplies, and abetted communication. Union control of the river would deprive the Confederacy of a main thoroughfare, divide the western Southern states from the eastern ones, and open the river to Northern traffic along its entire length. By June 1862, Union army and naval forces had captured New Orleans and many other forts and cities along the river. However, Vicksburg, Mississippi remained in Confederate hands. Situated on high, steep bluffs some 200 feet above the river and heavily defended by forts and earthworks, the city represented a major military challenge. Its ultimate surrender to General Ulysses S. Grant after a forty-seven-day siege was the culmination of a year-long land and naval campaign to capture this key strategic position. The fall of Vicksburg, combined with the defeat of General Robert E. Lee’s army at Gettysburg twenty-four hours earlier, marked the beginning of the end of the Confederacy.

Malaria is one of the world’s most common diseases: each year nearly 290 million people are infected, and more than 400,000 people die. Although the disease has been eradicated in most temperate zones with intensive mosquito control, it continues to be endemic throughout the tropics and subtropics. A French army surgeon in Algeria named Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran was the first to describe the life cycle of the malarial parasite. He observed pigmented parasites inside the red blood cells of malaria patients and was the first to recognize that these were the causative parasitic microorganisms. He further recognized that administering quinine removed the parasites from the blood. Laveran was the first to suggest that malaria was caused by a protozoan, for which he was awarded the 1907 Nobel Prize in Medicine.

The role of the female Anopheles mosquito as the transmitter of the disease was not determined until 1897, three decades after the Civil War ended. Sir Ronald Ross, a British physician officer in India, worked out the method of its spread. The parasite lives in this specific mosquito species and is transmitted between humans by a mosquito bite. Symptoms of malaria appear ten to fifteen days after a bite from an infected mosquito.

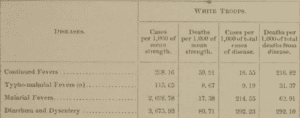

The diagnosis of malaria at the time of the Civil War was made by symptoms and not the laboratory tests we use today. Nineteenth-century physicians diagnosed malaria as a recurrent, intermittent, or “periodic” fever and categorized it according to how often fever spikes or “paroxysms” occurred. A “quotidian” fever occurs once every twenty-four hours, a “tertian” every forty-eight, and a “quartan” every seventy-two. An infection with Plasmodium vivax was commonly referred to as “intermittent fever” or “ague,” while Plasmodium falciparum was identified as “congestive intermittent fever,” “malignant fever,” or “pernicious malaria” because of its potentially lethal result. While P. falciparum was responsible for more than 80% of the deaths from malaria, its mortality ranged from 1–3% during the Civil War. Today the death rate is low at about 1/1,000.

Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (MSHWR) records show that one quarter of all illnesses in the Union army were malarial. In 1861 and 1862, about one-seventh of all cases of sickness reported by Rebel armies east of the Mississippi were malarial, and deaths from the disease were lower among Confederate soldiers. This is not surprising, since Southern soldiers had been exposed to the mosquitos previously, while Northern soldiers had not. However, as the war continued, malaria became more widespread throughout the Southern armies.

Malaria was considered the cause of death for roughly 30,000 soldiers. There were more than one million cases of malaria in the Union army during the war, resulting in about 10,000 deaths. Malaria accounted for almost 16% of the 6.5 million episodes of illnesses recorded among Union soldiers.

Quinine was widely used around the world to fight fevers from malaria and other diseases well before the Civil War. John Sappington, a physician in Missouri, usually receives credit for its widespread use in the United States. He tested quinine derived from cinchona bark on himself in 1823. He used his slaves to manufacture quinine pills that he then sold, becoming wealthy at a time when bloodletting was the standard therapeutic option. A pharmaceutical and chemical company named Farr and Kunzie was the first to manufacture quinine sulfate commercially in the United States.

Quinine was used both to prevent malaria in endemic areas and, at higher doses, to treat the illness. The relatively low rate of infection in the Union armies resulted in large part from the readily available supply of quinine. However, because of the naval blockade, Southern soldiers could not access quinine and had to resort to weaker native plants and medicinal herbs to combat the illness.

The Union army’s experience with the disease was somewhat alleviated by the availability of quinine. The Union army purchased more than nineteen tons of quinine and nine tons of cinchona fluid extract during the war. Three to six grains of quinine was routinely given for prophylaxis at the start of the war. Union army Surgeon General William A. Hammond developed the US Army Laboratory to ensure the purity of drugs and to create standards for drugs purchased by medical purveyors and distributed to the various theaters of war. Hammond struck a deal with a pharmaceutical company, Powers and Weightman, to lease space to the government to produce quinine under the command of John Michael Maisch, a trained pharmacologist.

In the spring of 1863, Grant opened the Vicksburg campaign. Gunboats of the “brown water navy” and troop transport ships ran the gauntlet of the batteries at Vicksburg at night. On April 29 and April 30, 1863, Grant’s army crossed the Mississippi River, landing at Bruinsburg, Mississippi. A clever sequence of diversions misled the Confederates as to Grant’s intentions, allowing Grant to move his entire army across the river without opposition. Grant’s decision to press on with his offensive despite a substantial incidence of malaria among his ranks at its high season makes that accomplishment even more impressive, although most accounts of the campaign fail to address this aspect of the operations. Grant succeeded in part because he had ample supplies of quinine.

Once across the river, Grant marched his army farther east and captured the state capital of Jackson, Mississippi by May 14. He then turned west, separating Pemberton and Johnston’s forces. The defeat of the Confederates in the Battle of Champion Hill on May 16 forced Pemberton to retreat further. In that pivotal battle, Pemberton was outnumbered 32,000 to 22,000. On May 17 at the Big Black River, a Union victory forced the Confederates to retreat to their fortifications at Vicksburg. On May 18, 1863, Grant’s army approached Vicksburg.

Pemberton’s army had created a strong defensive position. The constant bombardment from Union artillery drove the city’s residents underground, as the shelling made it impossible for them to walk the streets or live in their homes. The bombardments rendered nearly all surface structures unsafe or outright destroyed them. Some desperate residents and soldiers dug more than 500 caves into the hillside to escape the heavy artillery fire, while others hid in their basements. These caves were infested with rats and mosquitos, crowded, and poorly ventilated. There was not enough water to drink, and none for bathing or cleaning clothes; lice were universal. The soldiers endured diminished rations, exposure to the elements, and constant bombardment from naval gunboats and overland mortars. Despite being surrounded and having no access to food, weapons, or ammunition, Vicksburg’s civilians and defenders desperately fought on. Over time, Grant moved 77,000 Union soldiers into positions completely encircling Vicksburg, cutting off the Confederate supply line and forcing troops to subsist on horses, dogs, and vegetables stolen from the gardens of residents.

By the end of June, many Confederate soldiers suffered from malnutrition, including scurvy caused by a lack of Vitamin C. Other acute illnesses such as salmonella and shigella caused dysentery from the unsanitary conditions in the besieged city, a direct result of the combination of contaminated water, insufficient food, and poor hygiene. Infestations of insects and other vermin led to a communicable disease nightmare. These illnesses lowered the men’s resistance to malaria. Mosquitos were everywhere, living in brackish pools of water. More than 10,000 of Pemberton’s soldiers were rendered unfit for duty by various illnesses, combat wounds, and malnutrition.

Public buildings including hotels were jammed to capacity with the sick and wounded, and most surviving private residences were pressed into service as hospitals. But there was no quinine available, and all medicines were in extremely short supply. It is almost certain that many of those in the siege had several illnesses concurrently. Not only did inhabitants of Vicksburg consume mule and rat meat, but they also drank water from contaminated, muddy ponds. Toward the end of the siege, some were eating rats and tree bark. Because they were completely hemmed in by Grant’s army, there was no chance of escape. Many more men were dying of illness by July than in line of battle.

|

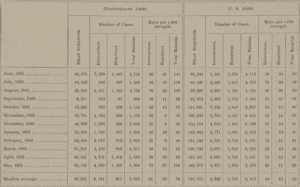

| Table 1. Incidence of Malaria in Two Armies (click to view). From MSWHR, Vol. 1, Part III, page 104. |

On June 28, Pemberton received a petition signed by many of his own troops, which stated in part, “If you cannot feed us you had better surrender.” On July 1, he queried his division commanders whether they should surrender or attempt an evacuation. The consensus was that disease and starvation had physically impaired so large a number of the defending army that an attempt to cut through the Union line would be disastrous; the men were too “enfeebled” to attempt an evacuation. On July 4, 1863, after a forty-seven-day siege, Pemberton surrendered to Grant.

During the final Vicksburg offensive, which lasted from May 18 to July 4, the Confederate army suffered 3,202 casualties with 875 deaths, while Grant’s operations against Vicksburg from April 15 to July 4 claimed 10,142 Union casualties with 1,581 deaths. During the siege, the Union army suffered 638 casualties with 94 deaths. Additionally, there were 381 Confederate deaths at the May 16 Battle of Champion Hill. At Vicksburg, the Confederates surrendered between 29,500–31,600 prisoners (depending on source), together with 172 cannons, 60,000 muskets, and a large amount of ammunition. The sick and weak Confederate soldiers were paroled.

How important was malaria to the military result? The military physicians in Vicksburg were not concerned about accurately diagnosing disease, but they were very careful about how many soldiers had to be out of active duty. The MSHWR does not specifically present malarial incidence in Mississippi at this time, but it does provide figures of the Confederate troops around Mobile, Alabama from January 1862 – July 1863: 1,420 cases per 1,000. In other words, almost every soldier had severe fever episodes and many experienced more than one. The Confederate Army of the Tennessee suffered 100 cases/1,000 in May 1863 as compared to 39/1,000 in the Union Army (Table 1). This 250% difference, in which there were 5,528 new reported cases that month, is as close to an actual number as we can get; it can be applied to Pemberton’s army as an underestimate. This figure has direct applicability to the Battle of Champion Hill but before the siege.

A substantial percentage of Grant’s Army of the Tennessee also contracted malaria during the siege. Union forces exposed to the Delta’s swamps experienced the highest incidence of malaria of any Union army, peaking at the end of the siege. The monthly incidences in June, July, and August 1863 were 116, 136, and 130 cases per 1,000 troops per month. Assuming 70,000 soldiers comprised the Union army, an incidence of 12–14% calculates to about 9,000 cases each month. Yet, the Union soldiers were well fed and lived relatively comfortably compared to the Confederate soldiers who were inside the city under siege. Union soldiers dug wells for water and foraged for food in the local area.

|

| Table 2. Rates of Mortality of Several Disease Entities in the Civil War (click to view). MSWHR, Vol. 1, Part III, page 11. |

By contrast, a significant number of the Confederate defenders were ill and absent from Pemberton’s command at the time of the battle of Champion Hill on May 16, 1863. The incidence of malaria reported in April and May 1863 in Bragg’s army was about 90/1,000. The loss of this crucial battle drove Pemberton back into a defensive position around Vicksburg. If Pemberton’s army had been at full field strength at the Battle of Champion Hill, with 2,700 additional men (9% of 30,000), it would not have been as outnumbered. Perhaps it might have repulsed Grant’s attacks, or even delayed the subsequent advance, preventing the Army of the Tennessee from initiating a siege.

The lack of manpower during the siege forced Confederate soldiers to remain on duty beyond the time frame of maximum effectiveness. Of Pemberton’s 30,000 men under siege, about half were unable to report for duty. If we simply apply the reported Union incidence of about 130 per 1,000, then minimally the incidence of malaria was 3,900 cases, and thus responsible for over 25% of those “unable to report to duty.” As this figure derives from the Union soldiers not under siege, it is the low-end estimate. As noted earlier, Confederate soldiers generally were 29% more likely to experience malaria, which would suggest as many as 5,031 active cases. And if we extrapolate to the figures in May 1863 in the Army of the Tennessee, again a conservative estimate, it may be that 295/1,000 soldiers had malaria, or 8,850: a remarkable 29.5% of the entire defensive force.

To summarize, estimates based on known incidences reported during the war suggests that 3,900–8,850 of Pemberton’s 30,000 men were suffering from active cases of malaria. An illness of this severity experienced in this magnitude certainly would have rendered the Confederate defense combat ineffective. There can be no surprise that Pemberton was forced to surrender given the disease prevalence in his army.

References

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press 1988), 333-34.

- Edwin C. Bearss, The Campaign for Vicksburg, 3 vols. (Dayton, OH: Morningside, 1986), 2:19-53.

- Timothy B. Smith, Champion Hill: Decisive Battle for Vicksburg (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas-Beatie, 2004).

- Timothy B. Smith, The Siege of Vicksburg: Climax of the Campaign to Open the Mississippi River, May 23-July 4, 1863 (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas-Beatie, 2021).

- Donald L. Miller, Vicksburg (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2019), 11; American Battlefield Trust.

- Alfred Jay Bollet, A.M. Bell, “Trans-Mississippi Miasmas: Malaria & Yellow Fellow Fever Shaped the Course of the Civil War in the Confederacy’s Western Theater,” East Texas Historical Journal 47 (2009).

- Andrew M. Bell, Mosquito Soldiers: Malaria, Yellow Fever, and the Course of the American Civil War (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010).

- A.J. Bollet. “The major infectious epidemic diseases of civil war soldiers,” Infect Dis Clin N Am 2004; 18: 298.

- The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (MSWHR). Volume 1, Part III. Washington Government Printing Office 1888, 77-184. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-14121350R-mvset.

DR. LLOYD W. KLEIN is Clinical Professor of Medicine in the Cardiology Division of the University of California, San Francisco. He is a nationally recognized cardiologist with over thirty-five years’ experience and is an amateur historian who has published extensively on the Civil War. He bears a particular interest in political and military leadership and their economic ramifications.

ERIC J. WITTENBERG is an award-winning Civil War author. Educated at Dickinson College and the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, he is an attorney in private practice in Columbus, Ohio. His Civil War studies have focused on mounted operations and on the Gettysburg campaign.

Winter 2023 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply