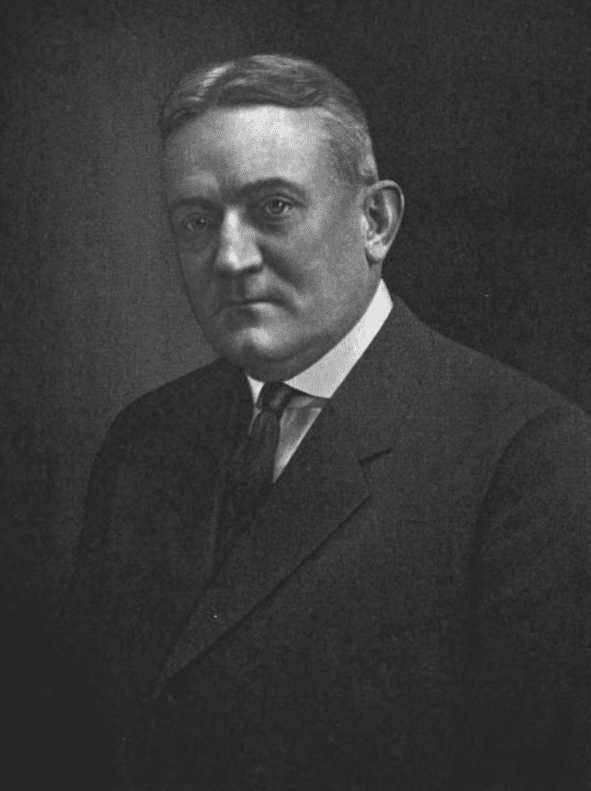

Portrait of Henry Andrews Cotton from Appleton’s Cyclopædia of American Biography, Vol. X, 1924, pages 324–325. Via Wikimedia. Public domain.

Dr. Henry Cotton believed that all mental illnesses were caused by chronic “focal” infections hidden in various organs. He argued that when these infections spread to the brain, they caused inflammation and mental disorders. To cure these conditions, Cotton advocated the aggressive surgical removal of the infected organ, and for this achieved considerable fame in the early twentieth century.

Born in New York in 1876, Cotton attended Columbia University and obtained a medical degree from Johns Hopkins in 1902. He studied with the most influential psychiatrists of his time: Emil Kraepelin and Alois Alzheimer in Europe and Adolph Meyer in America. In 1906 he became superintendent of the Trenton State Hospital in Trenton, New Jersey, and remained there as the absolute dictator until he died in 1933. He introduced many reforms, abolishing forced restraints, promoting occupational therapy, and organizing regular outpatient patient evaluation conferences. Stimulated by reports that infection with the spirochaete of syphilis could cause brain disease, he extrapolated this information to other mental disorders and postulated a “bacteriological model of madness” based on the theory of focal sepsis. Around 1913 he began removing patients’ teeth, then extended his treatments to tonsillectomies, and eventually to removing gall bladders, stomachs, uteruses, ovaries, testicles, and even colons. Though untrained in surgery, he carried out many of these operations himself. They were done without informed consent, and many were fatal. Some 30 to 40% of patients undergoing colectomy died, but by 1923, Cotton was claiming an 80% success rate for his treatments.

Cotton became famous for his new approach to mental diseases. He gave presentations to learned societies, published papers in professional journals, and welcomed visitors who came to observe his work at Trenton State. When in 1925 there arose some skepticism about his methods, Dr. Adolph Meyer sent his former student Dr. Phyllis Greenacre to investigate his work. She found his study protocols flawed, records chaotic, results falsified, and patients kept under unwholesome, overcrowded conditions, with many unable to speak or eat because their teeth had been removed. No action was taken, and Dr. Greenacre was reassigned to other duties. In response to patient complaints, the New Jersey Senate also carried out an investigation but found no problems and praised the doctor for saving the state money. Cotton later opened a lucrative private clinic in Trenton and to the end of his life continued to believe in his methods, even removing some of the teeth of his wife, his two children, and his own. He died suddenly of a heart attack in 1933. Though responsible for many deaths, he continued to be lauded for some time, both locally and internationally, as a pioneer in the treatment of psychiatric illnesses.

Reference

Philip R. Liebson. The talented Dr. Cotton and other quacks. Hektoen International History Essays, Summer 2021.

Leave a Reply